By Elena Basati,

Over the years, the number of people incarcerated in the United States has increased; this trend is known as mass incarceration. Because of the stricter sentencing rules, the jail setting is brutal and the conditions are severe. The environment is harsh and controlled, and many of the guards mistreat the inmates, leaving them in a deep state of hopelessness. Despite the cruel circumstances, prisoners frequently receive inadequate care instead of punishment, which worsens their already dire circumstances. Many questions arise about the effectiveness of prisons, including whether or not prisoners are treated properly and whether guards are not abusing their authority. In a jail environment, who is evil: the prisoner or the guard in power?

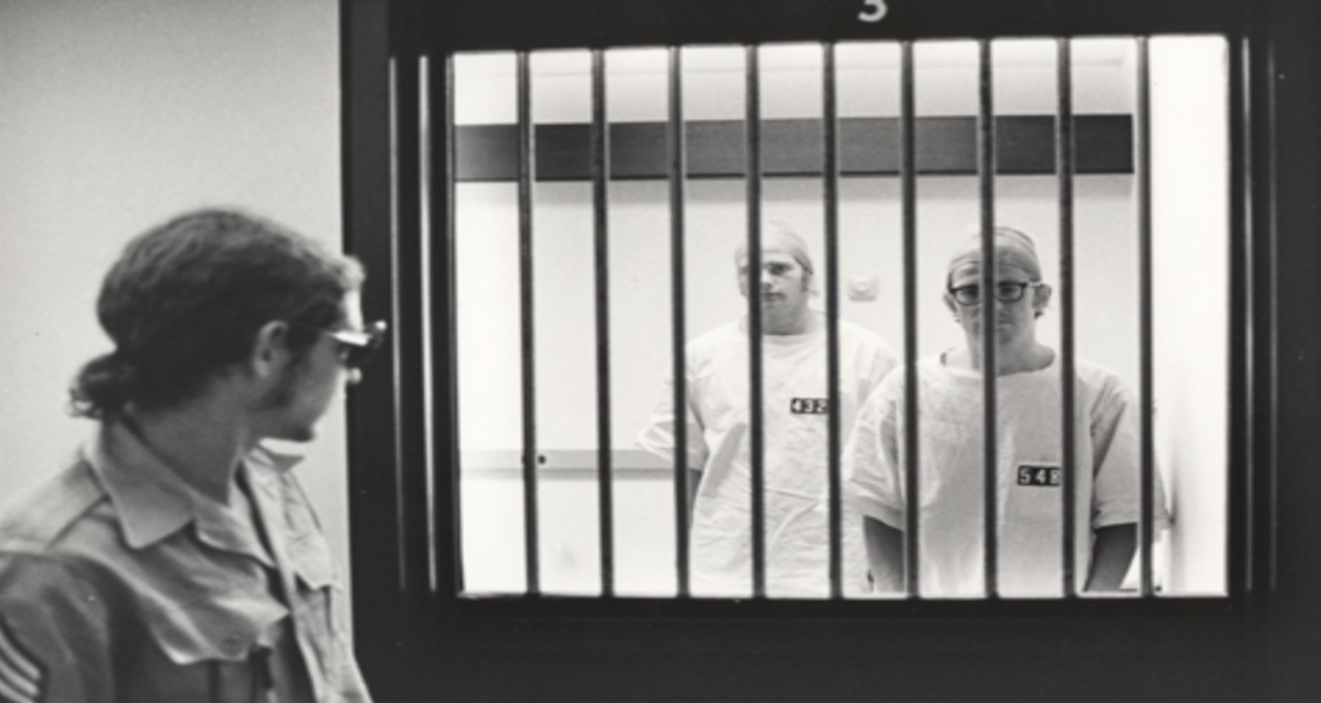

Although neither prisoners nor guards represent society at large, social psychologists in particular find the prison environment highly unique and have studied the former extensively. One of the most well-known instances is the Zimbardo experiment, carried out in 1971 at Stanford Prison. In particular, they set up a mock jail at Stanford University’s psychology department basement. Males between the ages of 17 and 30 who had responded to an advertisement in a newspaper about a two-week paid experiment on jail life were the participants. Without providing any guidance on performance, the experimenters randomly assigned each participant to be either a guard or a prisoner. On the first day, each participant-prisoner was “arrested” and taken to the police station where they would take their fingerprints. Then they were instructed to put on loose-fitting smocks with their number identifier, a nylon hair bag, and rubber sandals. On the other hand, the guards were dressed in khaki uniforms and were given nightsticks, handcuffs, reflector sunglasses, keys, and whistles. The rules demanded prisoners to be called by their identification numbers, get in line routinely, be fed three basic meals, and visit the toilet only three times a day.

The events took a wild turn very fast, leaving Zimbardo and his team startled. Some guards started abusing their power and became severely abusive. They harassed their inmates in many different ways, by waking them up in the middle of the night, forcing them into crowded rooms, and subjecting them to hard labor and solitary confinement. Interestingly, the guards were even more aggressive when they thought they were alone with a prisoner. Even though, in the beginning, the inmates started to rebel and confront the guards, as time passed, they were becoming more passive. In only 36 hours, the experimenters had to release a prisoner because he showed signs of acute depression and he wasn’t the only one. In 6 days, those left were so shaken by the study that Zimbardo himself decided to terminate the experiment.

The study, however, was heavily criticized and was considered unethical by many. Despite the moral dilemmas and concerns, the Stanford Experiment provided us with significant insights into the effects of authority on human behaviors. Another important question about the Stanford prison study has surfaced, which is similar to the one that is frequently asked about Milgram’s obedience experiments: Did the guards’ actions reflect the influence of the circumstances they were in, or were the men who participated in the study particularly violent? Seeking an answer to the question, Thomas Carnahan and Sam McFarland ran an interesting study where they placed two nearly identical newspaper ads. One of them, much like Zimbardo’s famous ad, specifically mentioned a study on “prison life”, while the other left out that part. What they found was striking: the people who signed up for the prison study scored higher on traits like aggression, authoritarianism, and narcissism, and lower on empathy and altruism.

This led the researchers to wonder if Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment had attracted people with a natural tendency toward antisocial behavior. In response, Haney and Zimbardo (2009) pointed out that participants in the original experiment had been tested, and no significant differences were found between them and the average population. Furthermore, there were no meaningful personality differences between the prisoners and guards in the study itself.

The Stanford Prison Experiment serves as a powerful illustration of how situational factors can profoundly influence human behavior, leading individuals to engage in actions they might never consider in their everyday lives. Zimbardo’s findings highlight the alarming capacity for ordinary people to commit acts of cruelty when placed in positions of authority, underscoring the concept of the “Authority Effect”. A stark real-world example of this phenomenon can be seen in the Abu Ghraib scandal, where U.S. military personnel abused prisoners in a similar manner to the guards in Zimbardo’s study. The questions still linger, how confident can we be for our own goodness, and how sure can we be of ourselves?

References

- Carnahan, T., & McFarland, S. (2007). “The Stanford prison study: A social psychological perspective”. Psychological Science, 18(6), 516-518.

- Haney, C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1998). “The social psychology of imprisonment: A psychological analysis of the Stanford prison experiment”. In J. M. Miller (Ed.), “The handbook of social psychology” (pp. 154-171). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Miller, C. (2019). “Illustrated guide to the national electrical code (MindTap course list) (8th ed.)”. Cengage Learning.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). “The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil”. Random House.