By Dimitris Kouvaras,

“Now I see fire; Inside the mountain; And I see fire; Burning the trees; And I see fire; Hollowing souls; And I see fire; Blood in the breeze”. A few days ago, Ed Sheeran’s lugubrious lyrics turned into reality, as flames engulfed the mountainous woodlands northeast of Athens. The East Attica wildfire, as it was named due to its location, started around 3.00 pm on Sunday, August 11th, in the small town of Varnavas, and soon spread rapidly in the hilly forestlands to the north of mount Penteli, dangerously close to the urban centre and various towns of the Attica area. Yet, it wasn’t a one-of-a-kind occasion. Every summer, disastrous wildfires plague Greece’s precious forestlands, often veering out of control and resulting in severe losses of natural habitat. Attica itself is one of the most heavily affected regions, which, according to the latest reports, has suffered the loss of 37% of its total woodland through 13 wildfires occurring since 2017, totaling an astonishing 45.000 hectares burnt.

According to the ongoing investigation by the interrogation unit of the Fire Department, the fire likely started near the asphalt at Amalthea Street in Varnavas, at a spot occupied by an electricity pole and cables. A 76-year-old man declared a potential issue with the pole, observing that some cables had been released from their holding position. The suggested cause is not unlikely, as other instances of electricity-induced fire have been observed in the last years, but remains unconfirmed. What probably started as a small blaze, spread rapidly due to the gusty winds blowing in the area, which were reported at 7 Beaufort and severely hindered the firefighting procedures. By 6.00 pm, the smoke had already diffused over Attica’s skies, giving them a dismal brownish look that made the bright afternoon light appear like a sunset. I witnessed that eerie atmosphere myself since, at the time, I was in a beach south of Athens.

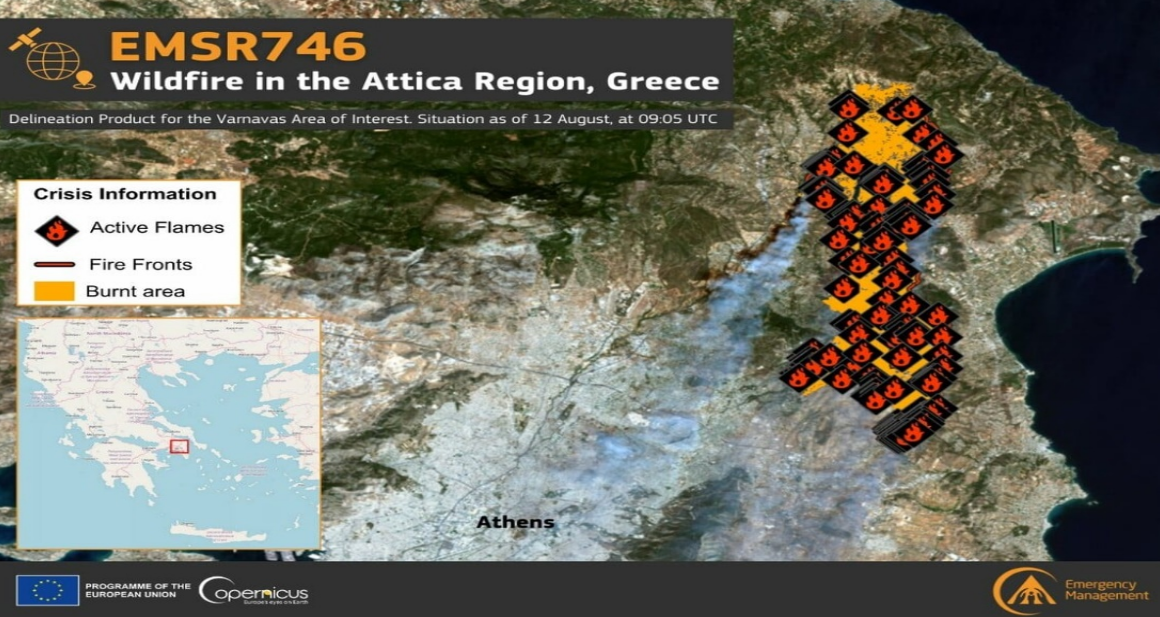

By Monday, the fire had already created a front of a whopping 23 kilometers in length, according to the European satellite service Copernicus, with major blazes threatening the areas of Marathon, Grammatiko and Penteli, leading to numerous evacuations of nearby towns and villages. Numerous houses surrendered to the flames, as people vainly tried to save their properties, and others evacuated to the South, as multiple warnings had been issued and transmitted to their phones by the government’s emergency messaging service, “112”. What led the disaster to its culmination and enabled it to make further headlines was that by Monday afternoon the fire was threatening the northeast suburbs of Athens, something that appeared inconceivable to many. Houses and businesses were destroyed in the areas of Chalandri and Vrilissia, which lay within the urban metropolitan area of Athens, and where the dense presence of buildings and infrastructure obstructed the use of airplanes to combat the fire. Nonetheless, helicopters still managed to perform targeted operations, while many locals and volunteers, and even members of the military forces, greatly helped the limited firefighting units throughout. In the area of Chalandri, a woman was found carbonised in the bathroom of the craft industry where she worked and from where she probably had tried to escape, becoming the first and –thankfully– only victim of the blaze. Starting from Tuesday, the ordeal steadily started to subside, as the many scattered hotspots were put off.

The natural toll is heartbreaking, estimated at between 8.500 and 10.000 hectares, raising pressing questions as to how this was allowed to happen. According to public records, a total of 702 firefighters with 199 vehicles and 35 aircrafts operated throughout the duration of the fire, which is a considerable number, and whose efforts, along with those of volunteers, residents, and police officers are praiseworthy. However, and despite the claim of Civil Protection Minister, Vasilis Kikilias, that the response time to Varnavas’ fire was just 5 minutes for the land and 7 for the aerial firefighting units, they proved too little to prevent the disaster. On the other hand, the quickness suggested by the above assertion renders it questionable and creates ground for suspicion, especially given the remoteness of the location and its proximity to housing infrastructure. After all, it wouldn’t be uncommon for Greek officials to resort to exaggerations to save public face. In any case, the government has come under fire about the lack of responsiveness that contradicts its claims earlier in the summer about a high level of preparedness, both by citizens on social media and other party leaders. SYRIZA’s (the Left opposition party) leader, Stefanos Kasselakis, requested evidence about the aircraft used, which led to no disproof of the original statistics, while PASOK (the centrist third party) demanded the expulsion of Mr. Kikilias, to no avail. One must note the communicational role of such acts, beside their political rationale. In any case, despite the pressure from the political spectrum, discussions in Parliament are offput until late August or September.

The two main questions arising are, in my opinion, the following: What is to be done to make up for the losses in property and infrastructure, and what are the chronic shortcomings leading to the perpetuation of wildfires every single summer? Regarding the first, an assessment of the damage has started, while businesses that were affected will receive a small indemnity, which does not suffice to get them back on track. For citizens, a solution awaits. A comprehensive plan should be put forward to support those who need it, prioritising those who lost their main or only residence.

The second question is even more important, because if such shortcomings are dealt with, the likelihood that the first question reappear each year -with all the expenses and logistic hurdles it brings with it- will become smaller. The answer is manifold and embraces both the state and individuals. A problematic legacy regarding the lawlessness of housebuilding close or within forestlands, especially of holiday homes, many of which have been constructed in spots difficult to access and without proper licensing, often becoming legalised via later acts. This is coupled by the lack of personal responsibility or state supervision of the implementation of proactive measures, such as clearing out any excessive or dry vegetation. Municipalities, which would be responsible for managing such initiatives, have proven to lack the will and means to enforce such provisions or shoulder the work, while the state appears either indifferent, or limitedly selective in its interventions, most of which occur after a major disaster and do not last long enough to prevent the next one. It is shocking to see that 60% of the woodland affected had already been burnt in 2009, according to the National Observatory.

Often, arson is the cause of wildfires, either premeditated or not, which is often hard to track, despite the current use of surveillance cameras and drones. Still, there is much to be done. Even the Canadair fleet is ageing, with production issues halting the production of new ones for years, while Greece lacks any firefighting aircraft able to safely operate in nighttime conditions. The consequences are many, and harmful to biodiversity, tourism, air quality, and even human life. Something must be done, as all excuses have also been consumed by the flames.

References

- Faulty power cable may have caused Greece’s worst wildfire this year, sources say. Reuters. Available here

- Deadly fires edge closer to Athens and suburbs count cost. BBC News. Available here

- Two-fifths of Attica’s forests have burned since 2017. Ekathimerini. Available here