By Katerina Taxiaropoulou,

“Woman Hollering Creek speaks from the silence, speaking freedom into existence and possible identity into being.”

“What is Called Heaven”, Jeff Thomson

A few minutes before dawn, somewhere in distant Mexico around 1915: A woman leans over a sleeping man and studies his every feature. The skin of his eyelids “as soft as the skin of the penis”, the long, elegant fingers smelling “sweet as [his] Havanas”. Yet, this soft skin shivers and these elegant fingers flinch. This is not just any man. This is Emiliano Zapata, El Caudillo del Sur, leader of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). And what about the woman? Is she just any woman? For many people, she bears no specific name. For Sandra Cisneros, her name is Inés Alfaro and she is a warrior.

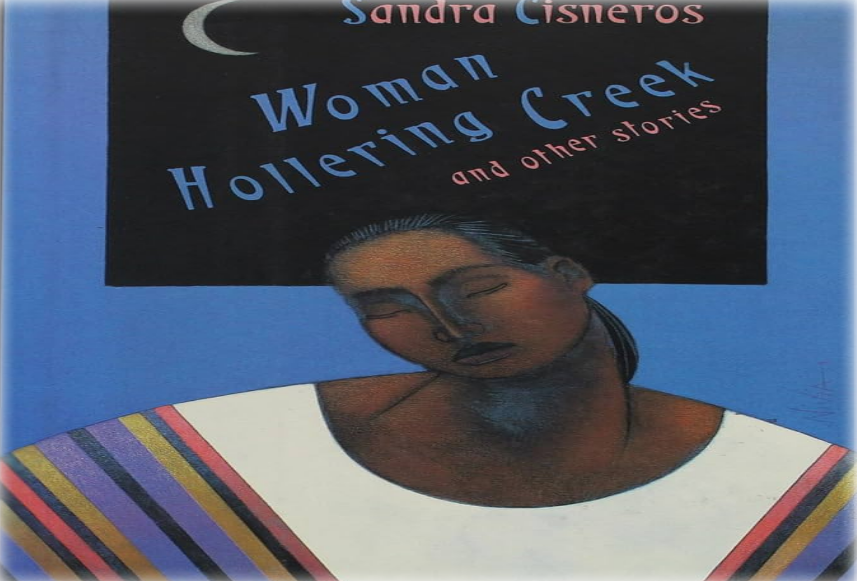

In her short story collection, Woman Hollering Creek (1991), Mexican-American writer Sandra Cisneros explores the social role of Chicanas, that is women living in the Mexican-US border. According to Fitts, these women mainly embody three “feminine clichés”: the submissive virgin, the wicked seductress and the treacherous mother (11). Living in an androcentric society, their shared experience is constructed by intersecting systems of oppression and a long struggle for selfhood. As a mistress to revolutionary Zapata, Inés defies the old traditions of ‘familismo’ and ‘marianismo’ and deconstructs the ‘virgin vs prostitute’ archetype through her multiple subjectivity.

1. Familismo

Inés rejects the value of self-sacrificing loyalty imposed by the macho culture of familismo, by not obeying her father’s proscription against uniting with a revolutionary. According to its encyclopedic entry, the term ‘familismo’ connotes a sense of “strong attachment” to one’s family (Morales and Pérez 247), suggesting a devotion to paternal desire, so absolute that it deprives the offspring of any independent will. In the tradition of familismo, the daughter would only unite in proper marriage with a man that has been formerly approved by the father.

Instead of delivering his wishes, Inés undoes the patriarchal pattern of female obedience and courageously abandons her father’s protective roof, eloping with the man of her choice. In Curiel’s phrasing, Zapata’s “robo” of Inés away from Remigo Alfaro “releases” her from the “responsibility” of protecting the latter’s name in society and satisfying his will in total obliteration of her own (412). This type of emancipation however has arrived with consequences. Once gone, she realizes she can never escape her father’s anger for the shame she has brought to the family. On top of it, she ends up doubly abandoned, as Zapata eventually refuses to “do the honorable thing” and marry her (414). Yet despite the pain, she stands by her choices heroically, raising her illegitimate children with independence and pride, which provokes society’s contempt.

In a more collectivistic sense of familismo, Inés betrays the unwritten moral law of the entire community, as she names her illegitimate daughter after her marginal mother. As Morales and Pérez clarify, familismo as a patriarchal structure also prescribes “commitment” to one’s “extended family” (247). In Inés’s androcentric reality, this summarizes all male citizens of Cuidad Ayala, since they constitute public personas with the authority to define ethical norms and exclude those they decide are deviant. Like her daughter, Marìa Elena retained an illicit affair, hence Redigo calls her a “perra”, meaning bitch. In this curse, he expresses a communal condemnation, foreshadowing “the extremes” phallocentric order will reach to secure male dominance (Curiel 418). Indeed, Marìa Elena’s rapists return her lifeless body, adding a man’s sombrero and a cigar, to demonstrate what happens to “women who try to act like men”.

Despite the trauma this twisted restoration of male justice has caused her, Inés names her daughter after her mother, without pleading for anyone’s permission or pardon. Rojas regards this act an instance of “reappropriation”, as Inés attempts to “reverse” the name’s derogatory connotations, “against a community that tried to erase [it]” (152). The villagers therefore marginalize her as the morally corrupt Other, attacking her with curses collectively. Yet still, Inés courageously makes the conscious decision to subvert patriarchal morality, giving the name Malena to her daughter, a product of her own liaison with a man.

2. Marianismo

At a meeting point of simultaneous and intersecting oppressions, Inés also defies marianismo’s sexist idealization of women’s chastity through her open sexual freedom and deep understanding of her female eroticism. The Wiley Encyclopedia entry to marianismo most of all emphasizes how Latinas are expected to remain “pure and asexual until marriage” (247). On the other hand, there is no clarification regarding the men, a fact that suggests either the absence of a prohibition, or the easy justification of premarital sexual activity for them.

A regular mistress to great Emiliano Zapata, Inés embodies the marginal role of the “sexually free woman”, and thus is used by Cisneros “to challenge the sexual double standard” that oppresses Chicanas (Curiel 404). Opposed to the stereotypical representation of the coy virgin, this character does not shy away from the naked body of a man lying in front of her. Right from the opening scene, Inés describes sleeping Zapata, employing a bold, sexually explicit language. Her sexual freedom causes her endless suffering under social hostility. Yet, she escapes the mental trap of macho ideology, demonstrating a profound “knowledge of and adeptness” in supporting her counterhegemonic female eroticism against aggression (Rojas 137). More mature in thought than the armed and ready hero, Inés states: “The wars begin here, in our hearts and in our beds”. She therefore embraces her sexuality as a powerful weapon, not as a criminal act against society.

Concurrently, Inés subverts marianismo’s model of female powerlessness through her first-person narrative, as she occupies the active position of the meaning-inscribing spectator. In the chauvinistic terms of marianismo, exemplary Mexican women are considered by default submissive to men. In this schema of silent docility, male orders define women’s life stories. On the contrary, Inés here liberates herself from the patriarchal muzzle, as she becomes “the central, speaking subject” of her own narrative (Curiel 417). As she lies above sleeping Zapata, Inés reflects upon her life, expressing all those previously muffled complaints, and revealing the concealed weakness of the man behind the facade of a hero. Underneath her, he remains unconscious, unable to silence her forceful speech.

Adding to his vulnerability, Zapata also misses his charro pants, a symbol for “traditional masculine strength” (Curiel 406). In this positional power shift, Inés observes the man’s private nakedness to render him rather frail and unimposing. As a result, she transforms the controlling ‘male gaze’ into a female one, becoming herself an active maker of meaning. Cisneros here undoes the phallocentric master-narrative by positioning Inés as the “speaking I/eye” of the text, retelling history from an emphatically feminine perspective (417). In her monologue, therefore, the character also voices a collective awareness of female oppression, and an urgent need for self-definition.

References

- Barbara B. Curiel. “The General’s Pants: A Chicana Feminist (Re)Vision of the Mexican Revolution in Sandra Cisneros’s ‘Eyes of Zapata’”. Western American Literature. V 35 n(4).

- Alejandro Morales, et al. “Marianismo”. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Clinical, Applied, and Cross‐Cultural Research.

- “Sandra Cisneros’s Modern Malinche: A Reconsideration of Feminine Archetypes in Woman Hollering Creek”. journals.lib.unb.ca. Available here

- Jeff Thomson. “What is Called Heaven’: Identity in Sandra Cisneros’s ‘Woman Hollering Creek’”. Studies in Short Fiction; Newberry. V 31 n(3)