By Frangiska Mylona,

Imagine the following clinical scenario; an adult woman is brought by her family into the emergency department due to an episode of convulsions. The family states that the woman does not have a history of seizures, she does not take any medication, however she suffers from severe alcoholism. The patient made an effort to cease drinking alcohol a few days ago and now, she is in an agitated state, diaphoretic and confused. The physical examination also shows that she has high blood pressure, tachycardia, along with bilateral hand tremors and fever.

Nevertheless, you are a good physician and you realize that the patient presents common alcohol withdrawal symptoms, and therefore, by recalling pharmacology, you are already familiar with the group of drugs that is indicated to stabilize the patient before you proceed to any further investigations.

These drugs are classified as benzodiazepines and they are very famous for their medical uses; they are prescribed as anxiolytics, they can exert hypnotic effects and thus they are prescribed for insomnia, as well also being indicated for seizures, in status epilepticus, in panic disorders, and for alcohol withdrawal. On top of that, some of them can be used as anesthetics, plus some sources state that they can be used also as a premedication during dental procedures.

As it is already mentioned, benzodiazepines have the ability to change one’s sleep cycle but they can also induce tolerance. Therefore, it is not advisable to be used in long-term when they are prescribed to treat insomnia. It is necessary, therewithal, for the patient to be informed about the sleep “hygiene”, which means the ability to maintain or start a beneficial sleeping cycle without the need for medications.

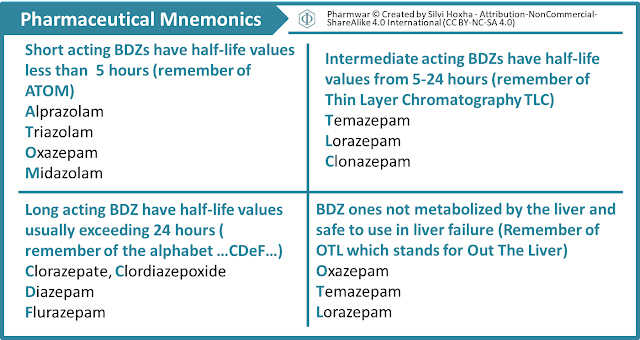

Specifically, benzodiazepines are divided into three groups based on their duration of action; the short-acting ones like Alprazolam (Xanax), the intermediate-acting ones like Lorazepam and the long-acting ones like Diazepam (Valium).

In spite of the differences in their duration, their mechanism of action is the same; they enhance the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter known as GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) in the ascending reticular activating system (RAS) in the brain. Benzodiazepines manage to exert these effects by binding near or on the GABAA receptor, intensifying the effects of GABA, and ultimately, slowing down the nerve impulses. The RAS system includes neurons in the cerebral cortex, limbic, thalamic and hypothalamic regions of the central nervous system (CNS) and it is associated with wakefulness and attention, where these functions are suppressed by the aforementioned group of drugs.

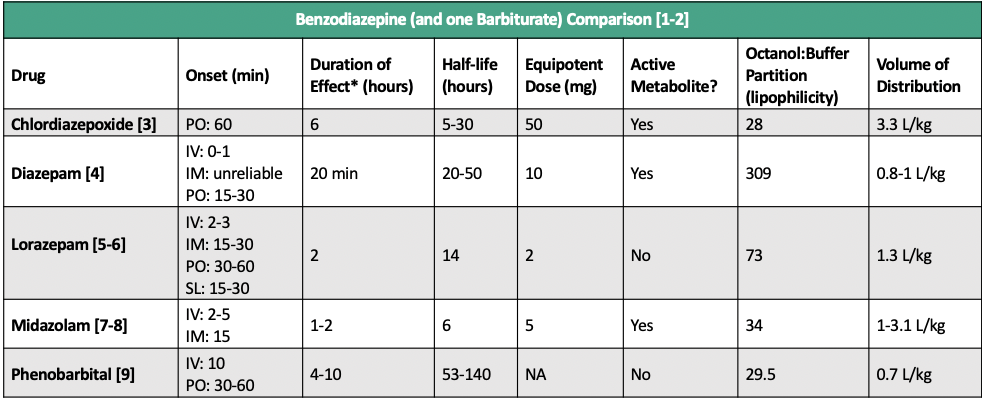

In regards to the drug’s pharmacokinetics, they are mostly given orally, although they can be administered in intravenous, intramuscular and in rectal forms when necessary. These drugs have a rather simple “journey” inside the body, since they are are absorbed rapidly and completely by the gastrointestinal tract and they can penetrate the brain quickly. Most of the benzodiazepines are metabolized in the liver and they are mostly excreted in the urine.

By potentiating the actions of GABA, they induce a state of calmness, relaxation and reduced anxiety to the patient. They can also cause drowsiness, ataxia, memory problems and sedation. Moreover, they decrease motor skills and they can lead to hypotension and confusion along with respiratory depression. In chronic cases of benzodiazepine toxicity, cognitive impairment is reported. Some very interesting side effects include anterograde amnesia, paradoxical reaction and an increased risk of bone, particularly hip fractures in elderly patients, since they lose their alertness and are more susceptible to falls.

One of the major challenges regarding benzodiazepines is the dependence phenomenon. Dependence in general is defined as the urge to take one drug repeatedly, and this is a possible scenario for patients prescribed these medications. Additionally, physical dependence is associated with the distress that follows when a drug is stopped, forcing the patient to keep on taking the drug so as to avoid its withdrawal symptoms. When it comes to benzodiazepines, dependence is apparent after 4 to 6 weeks, and it challenges the patient both physically and mentally. Some of these symptoms include vomiting, rebound anxiety, tachycardia, twitching, tremulousness and alteration of the mental status.

Therefore, it is advisable to inform the patient that there is a chance of developing dependence while administered these group of drugs and at the same time, it is mandatory for the physician to prescribe them for the shortest amount of time possible. Especially when it comes to the medication’s cessation, it should not be cut abruptly, but gradually and under the doctor’s guidance.

In conclusion, even though the “dream-like” effect sounds like the ideal and most euphoric state for someone to be in, it comes with consequences and possible deleterious ones. Hence, the doctor and the patient need to be in constant communication. Furthermore, it is crucial for the physician to be familiar with the risks involved during this medication’s administration, especially for vulnerable groups like the elderly ones.

References

- Suzanne Baron, Christoph Lee. Lange Pharmacology Flashcards, Fourth Edition 4th Edition. McGraw Hill / Medical. Chicago. 2017

- Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Pharmacology Made Incredibly Easy (Incredibly Easy! Series®) Fifth, North American Edition. LWW. Philadelphia. 2022.

- Philip Xiu & Shreelata Datta. Crash Course Pharmacology. Elsevier. Amsterdam. 2019.