By Carmen Chang,

In a previous article, we have presented the grammatical and lexical aspects of linguistic sexism, and in this section, we will focus on the ideological domain that often manifests unconsciously when we speak or express ourselves in everyday life. This linguistic phenomenon implies the discrimination, exclusion, and invisibility of women in all areas of life.

The incorporation of women into the paid labor force has highlighted the neglect of specification and has sparked criticism against the invisibility to which women have been subjected. In this sense, it can be affirmed that language (or linguistic usage, if preferred by some) has served an ideology that has concealed women, another manifestation of the silence to which we have historically been condemned.

Regarding the social invisibility of women, we can add what María Márquez (2013: 641-652) expressed in her book “Grammatical Gender and Sexist Discourse”:

“[…] Hence, it is not surprising at all our impression of exclusion or invisibility, which is not a matter of special ‘sensitivity’, but the interpretation inferred from being implicit in the use of certain communicative strategies. The key to understanding why protests have arisen from certain sectors of the population against ‘irregular’ uses of the generic masculine lies in the phrase ‘due to the conjunctural aims of the exchange’: the change in the communicative context, brought about by social transformations and the incorporation of women into the labor market, demands new linguistic specifications. The ‘invisibility’ of women is not an invention of feminists but a consequence of linguistically inadequate usage today”.

Regarding the previously mentioned, in the document “Désexisation et parité linguistique: le cas de la langue française” from the article “Pratiques et enjeux de la féminisation des désignations de personnes dans le discours médiatique de Suisse romande” by Sylvie Durrer (2002: 24-25), reference is made to the sexism present also in the writing of journalistic articles and how there is no clear established writing policy that takes this inclusion into account:

“In the framework of our research, we conducted an exploratory survey in each of the editorial offices of around fifteen Romand titles. We spent a day in each editorial office and conducted a series of voluntary and non-directive interviews. These exchanges allowed us to gather the following information. The issue of feminization and non-sexist writing is an eminently delicate, even stormy issue among journalists. Most editorial offices do not have a clear, explicit, and systematic policy in this matter. Many editorial offices have attempted, at least once, to collectively address the issue of feminization, but they have not been able to reach a consensus solution. The issue of lexical and discursive feminization currently constitutes, according to the journalists themselves, a real taboo in most editorial offices. It seems, however, that German-speaking editorial offices are somewhat less hesitant and more egalitarian in terms of gender-neutral writing”.

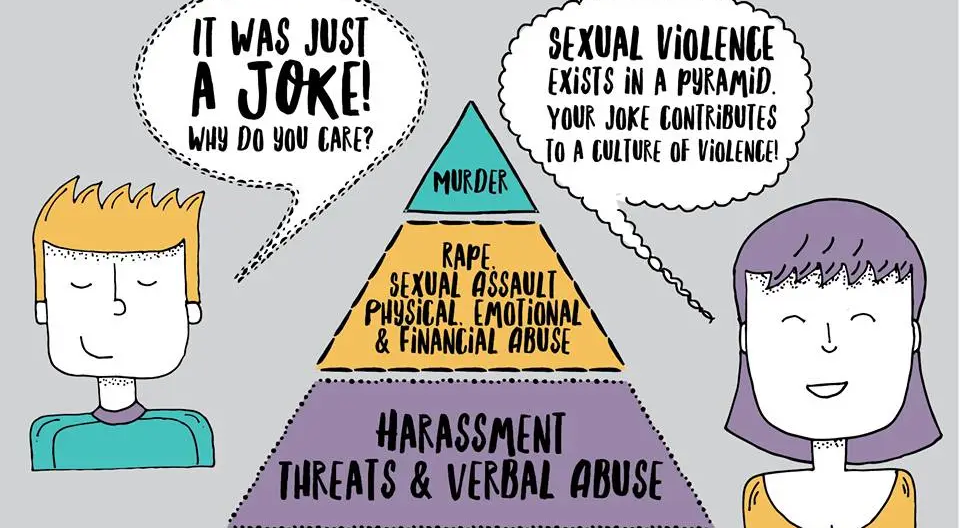

With regard to the above, in the article “Dialectique de la parole et du silence. Émergence et fonction de l’injure sexiste en politique” by Claire Oger (2006: 11-45), it is also mentioned that sexism extends to the political sphere:

“[…] an object like sexist insults in politics quickly explodes for the discourse analyst into a multitude of facets that call for a narrowing of the corpus and problems. In the absence of variation in the theme—sexual insult in its most elementary form dominates so widely that it remains emblematic (Oger, 2005)—, the enunciators know how to diversify the occasions and supports: politicians, right-wing or left-wing, activists, hosts, voters, and even journalists, men or women, indulge in it on occasion, making television shows, articles in the written press, electoral posters, ballots, parliamentary taunts, the place of inscription of obscene remarks whose common objective appears without difficulty: to disqualify female politicians, to deny them any form of legitimacy”.

To conclude this section, we want to express that we consider it essential for society to be responsible for a change in mentality and for this to manifest in the adoption of inclusive terms and expressions to avoid the invisibility of women:

“Most acts of invisibility are unconsciously carried out by their authors, who share dominant ethnocentric, gender, and sexuality paradigms. In this sense, invisibility is a process that derives from the construction of the concept of ‘the other’ or ‘others’ in opposition to ‘us.’ The consequences are not only psychological (destruction of self-esteem, of one’s own identity) but also legal, economic, etc. Often, there are significant economic interests behind any invisibility process, which is always a very effective indirect way of exercising domination. The discourse of power spreads in the family, in school, in the media, etc., and causes a lack of representation that leads to oblivion. Processes of invisibility are carried out through identity suppression mechanisms that damage the collective memory of the affected group. Social exclusion translates into discursive silence: the existence of the group is hidden by eliminating its voice, destroying the documents that attest to its identity and its social activity, not reflecting its presence in history. Sometimes, the term ‘memoricide’ is used to refer to the destruction of all verbal and non-verbal traces of that group (I. Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine 2007: 298). […] the concept of visibilization: unveiling what remains hidden”.

References

- María Márquez. Género gramatical y discurso sexista (Perspectiva Feminista). Editorial Síntesis, S. A. Madrid. 2013.

- Véronique Perry. “Désexisation et parité linguistique: le cas de la langue française, Ateliers 3 et 30 dans le cadre du 3ème”. Colloque international des recherches féministes francophones. p. 24-25.

- Claire Oger. “Dialectique de la parole et du silence”. Émergence et fonction de l’injure sexiste en politique. VOL. 25/1. p. 11-45.