By Dimitris Kouvaras,

The Palestinian land has suffered for long. Countless bodies have fallen lifeless on it during the myriad of conflicts it has witnessed, fought with swords and arrows, bullets, and missiles. Screw the land; it is no more than dirt, albeit bloodied. The ones who suffer are its people, a population predominantly young and composed of children and youth, a fact that has little changed over time, especially in the Arab regions. Nowadays, a new conflict has begun, after Hamas -an extremist nationalist Muslim revolutionary organization in control of Gaza- took Israel by surprise and launched a ruthless campaign on its soil. The latter seeks a harsh retaliation by invading the strip and endangering the lives of thousands upon thousands. Ruthlessness is endemic on both sides.

How come this deadlock was reached? History alone can explain, or at least contextualize the situation, which is what the given part of the article will focus on. Today the facts are pretty much as follows: two religiously and ethnically different people, of which one has a state (Israel) and another doesn’t (Palestinians), are struggling for their respective rights to the same land. However, it would be of use to take a step back and delve into the past, debunking some myths along the way.

Decisively for the conflict’s understanding, at its core lay the historical processes leading to land appropriation by both sides; an intersectionality of settling precedent, culture, religion, and politics. None of the above factors could be sustained as its single cause. Equally important, it is and has forever been, an internationally mediated conflict, fostered by the geopolitical intrigue around the Middle East, a region of vital importance for its oil, resources, sea access, and links to the Asian trade routes. Be it ancient empires, such as the Babylonian, or modern ones, like the British, the great powers of each time played a crucial part in controlling the Palestinian region and inviting or deposing populations.

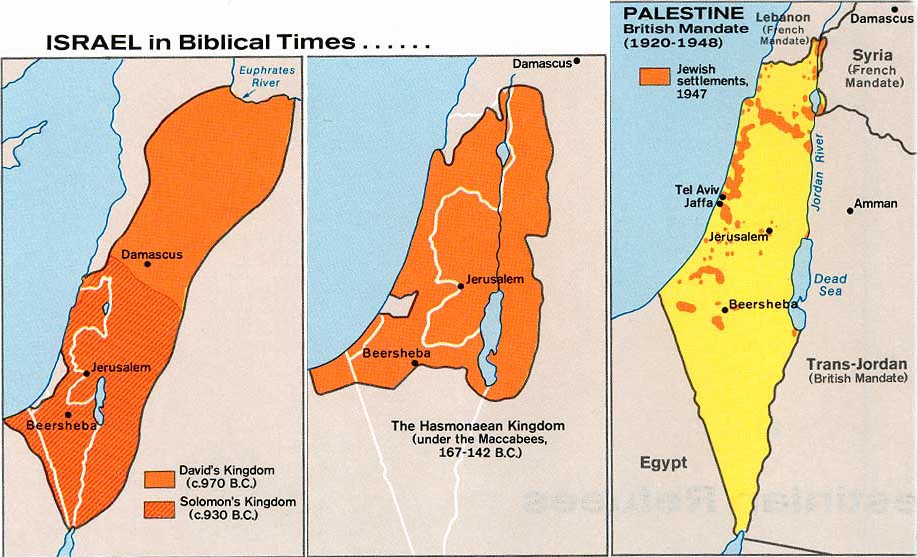

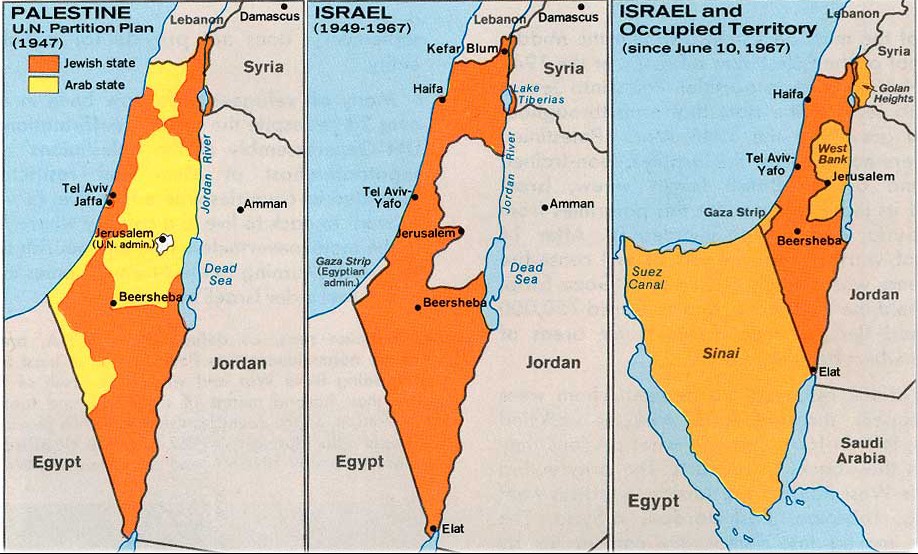

The so-called “Israelites” (from the name “Israel” given to biblical Jacob), who would later be referred to as Jews, arrived first in arid Palestine around the 12 century BCE, gradually developing a strict monotheist religion permeating all aspects of daily life via a complex ritual, the “law”. Palestine (from the Greek “Philistia”, a possessive adjective for the region referring to the presence of another ancient people) was supposedly granted to them by God after their flee from Egypt: a holy land for a chosen people. As such, was pivotal to their identity construction; that of a people whose unique, all-embracing religion, encompassing or closely intertwined with political authority and signifying emancipation, created a strong sense of community: that of a “proto-nation”, perceived by both them and their opponents. Due to foreign conquests of Palestine, from the 6th century BCE until modern times, the Jews spread all over the eastern Mediterranean and Europe, then also the US. Their Diaspora was often met with discrimination, limitations, exiles, and slaughters under the pretext of religion, but it was also their primary advantage.

Ironically, what fuelled antisemitism on a political level, especially in medieval and modern times, was that Jews developed, and at first monopolized, novel financial mechanisms, capturing key lending and banking roles, which made them potent, and wealthy but disliked. Nationalism became the leading cause in the 19th century, as Jews remained religiously and ethnically “foreign”, appearing as a coherent unity withstanding total assimilation. However, despite its oddities and resistances, the Jewish Diaspora had been diachronically part of “Western” space and culture; it was integrated into the nascent “international system” emerging from the 16th century onwards in terms of information handling, finance, familiarity, and interplay with its political culture and diplomacy, even more in the late 19th century. All they were missing was a state. Zionism, the Jewish nationalist movement, gained momentum after Theodor Herlz politicized the question of a home in Palestine in the 1890s, while settlements of oppressed Jews from Eastern Europe slowly began, often subsidized by Zionists.

Meanwhile, Palestine had been predominantly Arab since the 7th century AD. Islam, another Abrahamic religion centered on the prophet Muhammad, recognized Jerusalem as the holy sight of his rise towards Allah. It was the legitimization source for any secular authority and entailed its broad ritual. For the record, Jihad (holy war) is not among the fundamental obligations of Muslims. In the 19th century, Palestinian Arabs began forming their own localized identity under indirect Ottoman rule but were still unaffected by nationalism. For imperialist Europe, their culture was peripheral. 700,000 Arabs inhabited Palestine in 1914, against around 70,000 ultra-orthodox Jews. Again: This was an Arab land.

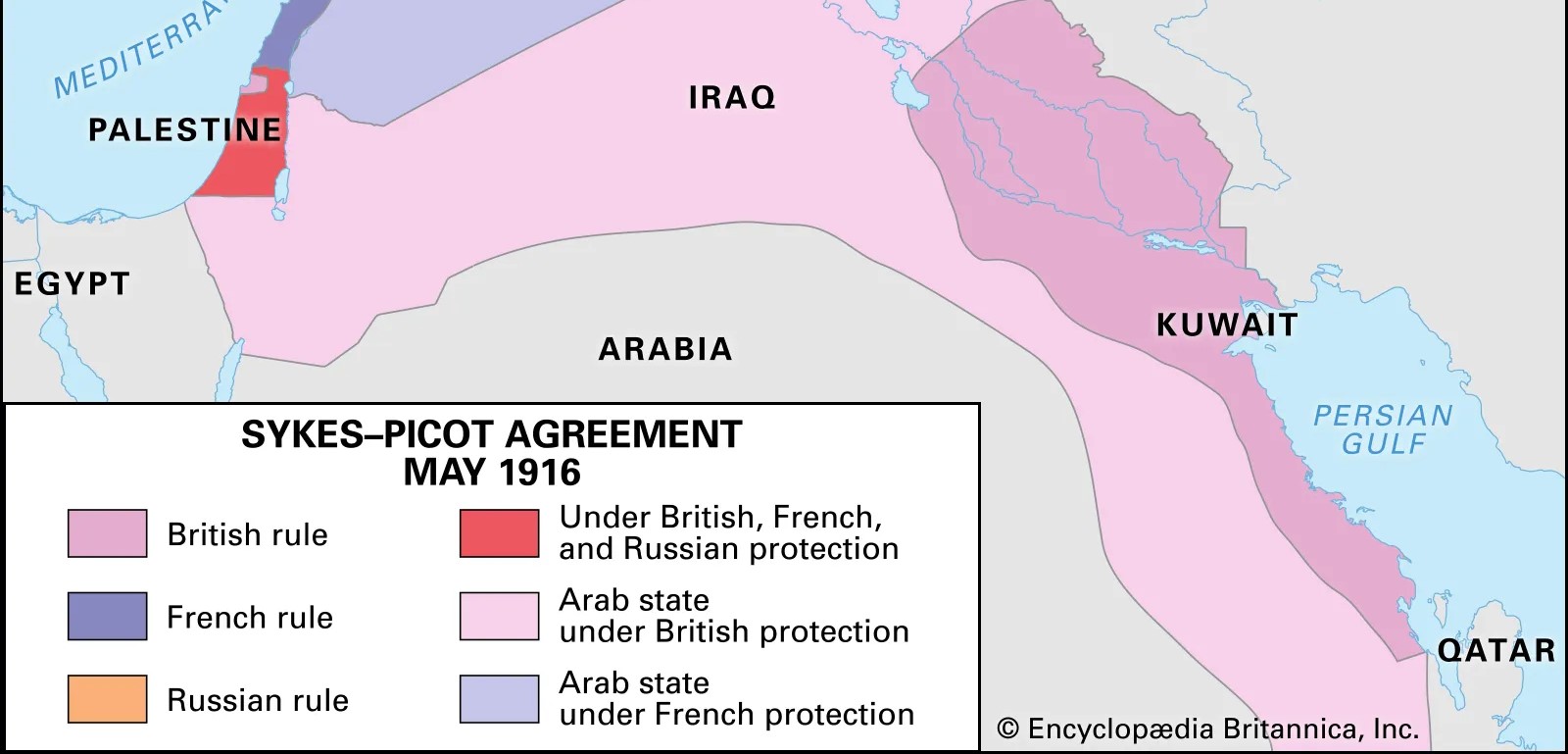

World War I became the catalyst for the creation of the duality permeating the conflict to this day. The Allies wanted to attack the Ottoman Empire’s middle eastern underbelly to distract the Central Powers from the stagnant European front and gain control over its prime location and resources. The British played a double game. On the one hand, an Arab uprising under Ali Hussein was incited by false promises of independence; on the other, Zionists were promised support in their schemes by the Balfour Declaration. What motivated this course of action was an attempt to seduce the Jewish lobby to trick the US into joining the war, and to divert Jews from communist affiliations. This not only overestimated Jewish influence but essentialized them as a single state desiring unity, which was not the case as the existence of internationalist Jews attests. It made political sense though, as an Israeli state would be under direct Western influence, making it a strategic, and institutionally correspondent, ally. For the moment, though, Britain and France arbitrarily carved the Middle East for themselves.

Palestine became a British mandate. Jewish immigration increased with the approval of the League of Nations and under the influence of war and interwar antisemitism, especially in Germany. The Arabs felt betrayed since their nationalist aspirations were at once awakened and sedated. The influx of agrarian Jewish settlements caused conflicts over land, a traditionally Arab field of economic activity, as they refused to sell or cede it. From their point of view, their land was being colonized. From a European imperialist standpoint, their non-Western culture didn’t meet the requirements for statehood. Still more, such a thing would be politically inefficient for the region’s control. During the 1930s, Jews in Palestine surpassed 300.000. Open Arab revolts sparked in the period 1936-1939, which forced the British to stop immigration. Nevertheless, the seeds of the present conflict had been sowed already by a combination of the eruption of Jewish and Arabic nationalisms, imperialist mindset and intrigue, as well as European antisemitism, which provided a cause -and an excuse- for the “artificial”, if I may be allowed the word, Jewish colonization of Palestine.

But wasn’t it a re-colonization? Historically speaking, no. Such an interpretation would be based on an essentialisation of the Jewish nation, necessary to support that Palestine is righteously its land no matter the era. This, however, would be a serious historical fallacy. It would mean omitting fourteen centuries of Arab presence and control. In any case, though, this development was in the political interest of the European powers of the time and soothed their internal pressing issue of antisemitism. It also made Palestine a ticking bomb, so that when World War II ended, the British wanted to leave it before it burst. What followed was the dichotomization of the territory between Jews and Palestinians, the immediate antecedent of the modern conflict, which will be presented in the second part of this article.

References

- Mika Ahuvia, Judaism, Jewish history, and anti-Jewish prejudice: An overview, Stroum Center for Jewish Studies. Available here

- Israel – Story of a contested country, DW Documentary. Available here

- What Ignited The Ongoing Palestine vs Israel Conflict: Promises & Betrayals, Timeline. Available here