By Evi Tsakali,

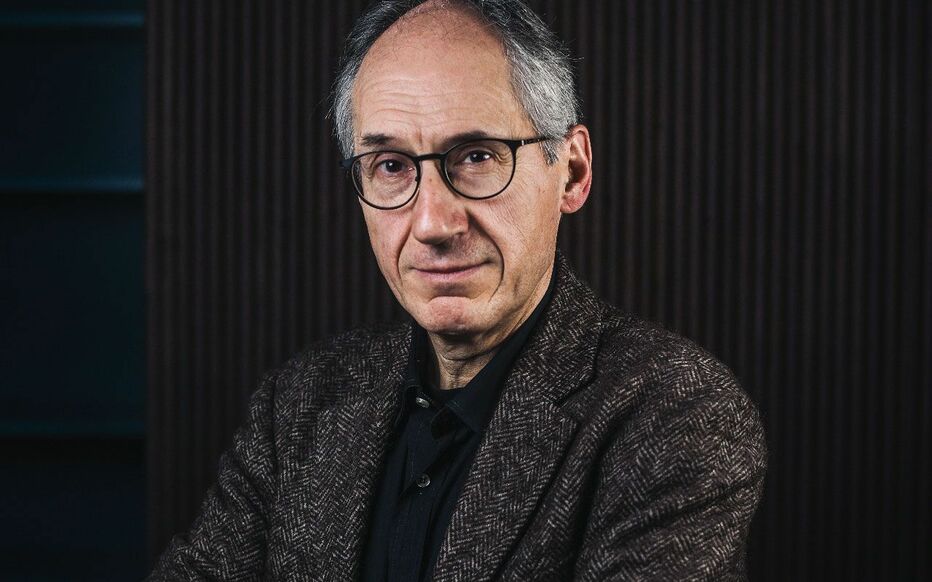

As my friends and close ones have understood (and my mailbox in France even better), I am a proud Charlie Hebdo subscriber. The weekly newspaper, that had moved me so much when, as a 14-year-old, I watched it become a worldwide symbol of freedom of speech and resistance against terrorism and fear, became a regular habit since I moved to Paris to study; I even attempted a spontaneous internship application at their headquarters only to find out (to their honor they replied very soon) that they can’t accept any interns because of the fact that, since the 2015 attacks, they are forced to work under really strict security measures. Working for Charlie Hebdo will never be the same anymore… Suffice it to say, bearing in mind the aforementioned, that when I was informed that a student association at my university would host an event with Charlie Hebdo’s editor-in-chief, Gérard Biard, it was one of my rare fangirling moments.

The security measures at the event were no joke, and it is understandable in France of 2021, where comedians say —when referring to terrorist attacks— “mais ça date un peu” (“but it’s been a while [since the last terrorist attack]”). We had to show identification and our bags for control, plus police forces were securing the perimeter and patrolling the neighborhood. It is indispensable to remind you at this point that, most of Charlie Hebdo’s journalists live under police protection since the 2015 attacks that cost them some of their colleagues, and Gérard Biard is no exception. Taking into consideration his living and work conditions, as well as the context in France, where we are marking a year since Samuel Paty’s decapitation by an Islam extremist (a minute of silence was also held at La Sorbonne during our lessons), it was an immense honor and pleasure to have him at a college amphitheater responding to students’ questions. I tried to regroup some of them to get you into the spirit.

What is Charlie Hebdo and how did it start?

Charlie Hebdo was founded in 1970 after its predecessor “Hara-Kiri” was banned by the French state; it was the product of censorship. It is a satiric newspaper, which means that it is rude by nature; satyr was never supposed to be polite anyway (Gérard Biard added to that point that reading and understanding satyr requires having a certain political culture, in addition to the fact that, when it comes to satiric journals like Charlie Hebdo, many interpretations are possible). It is also a “laïque” journal (I have dedicated a previous article of mine to a further explanation of the notion of laïcité), which means that it fully supports its right to blasphemy (droit au blasphème), with its team consisting, however, of both atheists and religious people. Regarding that, our guest made a much-needed distinction between faith, a notion so intimate and private, and religion, which is the social organization of faith; it is religion and not faith that French laïcité and Charlie Hebdo attack. For Gérard Biard, making a girl not wear her niqab at school (which is the case in France) is a small step towards her emancipation; because, for the first time in her life, it will be like being told “the choice is yours”, she is going to experience the life without wearing the niqab (without the intervention of her family), and one day she will be able to decide whether she wants to keep it or not. And that is possible only in a laïque state.

Who is Charlie today?

Charlie is the one who represents all the values that Charlie Hebdo promotes; the one who is anti-racist, the one who supports freedom of expression, the one who criticizes power in a constructive way (and blasphemy is not a necessary prerequisite). It is no secret that Charlie Hebdo often hosts opposing opinions within the same paper (such as ecological matters or a 2013 law regarding prostitution in France that penalized the clients). Charlie does not proceed to any kind of auto-censorship (one of the rare occasions of auto-censorship that the editor in chief could recall, was a time when an editor had prepared a satiric strip on Jacques Chirac’s handicapped daughter; they decided not to publish it of course).

Charlie Hebdo‘s point of view on Affaire Mila

It was only natural that someone from the audience would pose that question; many have drawn parallels between the case of Charlie Hebdo and that of young Mila (as I have mentioned in the article on Affaire Mila). Gérard Biard, underlining the fact that she is only a young girl of 17 years (soon to be 18), replied that, like Charlie Hebdo can’t deny its purpose —to express itself freely via the press, analogically Mila can’t deny her purpose— to express herself on her social media. He then added that, if he —a 62-year-old man— finds living under police protection unbearable, then Mila (who also receives multiple life threats per minute) is the bravest of us all.

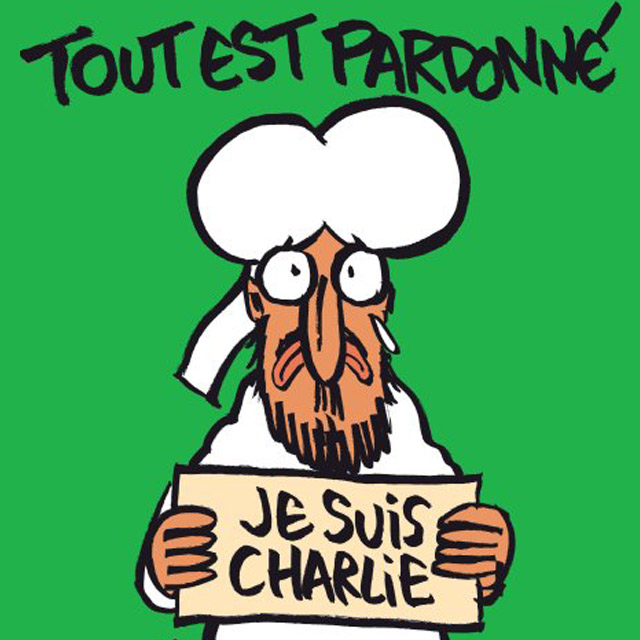

Tout est pardonné (?)

I left my personal favorite for the end. The cover of Charlie Hebdo’s first issue after the 2015 attacks featured a big-lettered “Tout est pardonné” (“Everything is forgiven”), which instigated a lot of controversy within the public opinion. When asked about that, Biard explained that —while the international opinion and media romanticized the drama and spread the symbolic “Je suis Charlie” (which they would soon forget, if they ever understood its real essence)— they didn’t want to be the victims. This is also the reason why —when they called him a hero for continuing to exercise active journalism in the same provocative manner despite living under police protection and with his life at stake in any minute—, he stated: “Je n’ai pas envie d’être héros, mais j’ai envie d’ être libre” (“I don’t want to be a hero, but I want to be free”).

Further reading (the link to Charlie Hebdo if you were not expecting it) is available here.