By Mado Gianni,

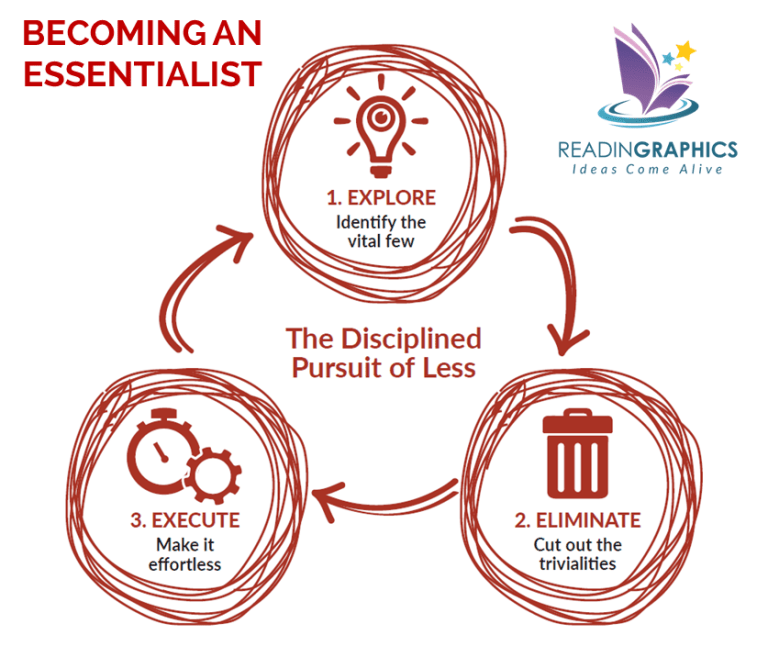

Whilst reading “Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less” by Greg McKeown, a must-read book which I believe should be taught in schools, I couldn’t help but think that the logic with which McKeown operates is not compatible with the Greek logic of doing things. In this article, I will make some connections between the idea of essentialism as put forward in “Essentialism” and the nonessential core of Greek society. For the sake of the argument, I will be speaking in an aphoristic manner. Please note: I do not suppose that all Greeks are like that but this is a rather wider understanding of where our country finds itself in the global spectrum.

Essentialism, in its definition and its book title, abides to the doctrine -or so to say- of “less but better”. That principle is, in its nature, anti-Greek. In 21st century Greece, one thing is definitely certain: the more things you do the more you can achieve. Why is this so and how did it form itself into a cultural assumption?

My indeterminate reading of the situation is that we Greeks set the bar real low for ourselves. We say, “If I do the bare minimum, I am still better than the rest who are doing nothing.”. The outcome of this logic is that, in doing many different things -even if it’s just the bare minimum each time- you are actually promoting yourself into being a multi-faceted human or business. It is complicated to explain but it is kind of a syndrome which Greeks suffer from. Why does this happen? Well, the simplest answer to that question is because we live in the ideal country. We love our country. We love our culture. Hence, we already have what those in other countries have to work hard to achieve. So, it’s only expected that our motivation is diminished and our efforts into being the better version of ourselves have to be cut short as well.

But this alone is not enough to explain our super distracted sense of success. Greek people are smart. They are smart because they learn from the horse’s mouth: we are exposed to Aristotle and Socrates before learning a different language. Smart as in cultured, not smart as in intelligent. Intelligence is a personal characteristic, and it is not what I am referring to: not to say that Greek people are not intelligent. Similarly, and to avoid any misunderstandings, I don’t mean that other nationalities are less cultured or that all Greeks are cultured. But it is an aphorism and a hard-worn stereotype, the same way that the French are romantic, and Germans are organised. The problem with this stereotype, however, is that for some reason, either divine or stupid, Greeks think they are smarter than all others.

The way this manifests itself in Greek society is that we believe that some things don’t apply to us. When McKeown talks about opinion overload (p.15), I think about all the times I have witnessed advising and consulting as the main plan of action before doing anything. When McKeown talks about the importance of DARING to say no, my mind goes to our ingrained sense of making friends with our colleagues or our bosses and the inevitability of maintaining a boundary that would allow us to say no to something. Most importantly, Greeks believe that they can cheat their way to success by manipulating time. From not studying until the last minute to working late on deadlines for one’s company, this logic infiltrates our minds and becomes a guiding principle in everything else that we do. Have you ever wondered why there are all these cars illegally parked or stationed in the centre of every big Greek city? If you ever ask a driver about it, they will tell you “I will be a minute.”.

Very similar to that faulty perception of being better than others is the idea that radical spontaneity beats even the highest level of organisation. McKeown in his last chapter “Execution”, where he gives solutions to adopting an essentialist lifestyle, refers to buffers as an ultimately valuable tool. He argues that humans cannot possibly predict everything. The solution to being as prepared as possible to face an unpredictability is by factoring in space or time for an unpredictable circumstance. In the Greek perception, this would be unheard of. And I think I have an explanation for this kind of behaviour. The author states that an essentialist “uses the good times to create a buffer for the bad ones” (p.180): Greeks don’t want to waste a living minute of our good time under the sun (quite literally) to prepare for a time of need, an unexpected situation or something that has always exhibited the probability of existing and which we have decided to continuously ignore, until we have to confront it.

The last point that McKeown refers to and which I think has direct relevance to my argument, is the power of FLOW or the genius of routine (p. 203). He argues “without routine, the power of nonessential distractions will overpower us.” (p. 206). Routines can be right, and they can be wrong; healthy or unhealthy; productive or not. Yet, what routine as a term is one hundred percent contradictory to, is spontaneity. You cannot have a routine if you don’t have a framework. In a culture where our motivation is not very strong since we constantly exploit the privilege of defining what failure is, and in which our idea of success comes through outsmarting others, operating under a right-willed routine is not even on the agenda.

On a positive note, there are some negative attitudes that McKeown raises which Greek people inherently don’t do. For example, Greeks are not known for their high levels of stress, lack of sleep or lack of play. We always find the time to do the things that make us happy, taking care of our mental health and hence creating room for innovation and creativity. Another point is raised in the chapter about FOCUS and the importance of living in the moment. In Greece, most people live in the moment most of the time. That is the norm. McKeown is right, being focused takes away from the anxiety, the depression or anything else that might be caused due to human carelessness and avoidance of our emotions. Yet, even we Greeks as much laid back as we pride ourselves in being, we cannot eliminate stress in its entirety. We push ‘it’ back to the last possible minute but there it is, manifesting itself right before a big deadline or an important interview.

Humans are not born with stress. Stress is a disorder that is caused by our interaction with the physical world around us. Resorting to spirituality -be it religion or activities such as mindfulness, yoga, tai chi etc.- is a way to eliminate stress. Yet, you cannot have everything without undergoing any kind of change. Relating to only a couple of attitudes that McKeown has listed in his book while being defined by the most nonessentialist principles that he identifies, unfortunately does not make us Greeks either smarter or more productive. It makes us nonessentialists at our core. In the last chapter, the author explains how Essentialism is not a thing to do but a thing to be. The more you conform to that logic, the more you become an essentialist by lifestyle.

This can work as a parallel to a lot of things that happen in the world right now, one of which is our response to living an eco-friendly life. Everything in life is a matter of getting used to. The more faith, effort or thinking you channel into a particular direction, the more you become it. If you change your habits towards the environment, your response to the reality of climate change will change. If you start living by the way of an essentialist, you will be surprised to see how effortless living can be.

References

- Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less, Gregor McKeown (2014).