By Maria-Nefeli Andredaki,

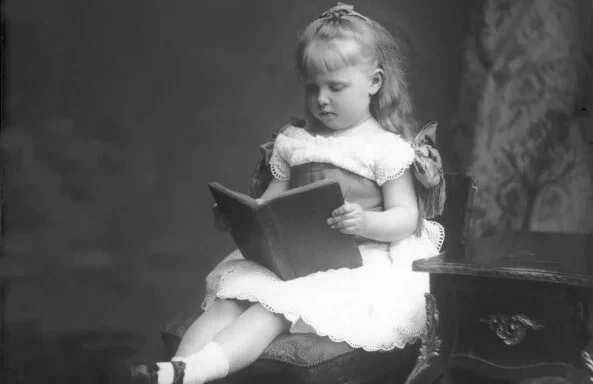

“Ever since there were children, there has been children’s literature”. This is the opening line of Seth Lerer’s book, “Children’s Literature-A reader’s history from Aesop to Harry Potter” which I got my hands on quite recently. As an English Literature graduate and a teacher, this book combines my two worlds perfectly and acts as an insightful history guide for anyone who wants to learn more about the subject and use it in their classroom.

For many years —and by many individuals— children’s literature has been seen as inferior, not worthy of study and analysis. Just stories for young audiences to stay occupied. This take is, of course, plainly false. Literature has an educational purpose; it critiques and affirms values, it sets examples and provides explanations. It speaks to an author’s or people’s troubles, cultural and social situations. It brings hope and showcases resilience. And you best believe that all of the above can be found in children’s literature too!

Before we talk history, let’s get familiar with what children’s literature consists of. First of all, children’s literature is self-aware and puts the child at the center of attention. Children (human or not) are, most of the time, the main subject and the main character, providing young readers a way to see themselves in the story, whether they realize it or not. Another feature is the didactic purpose that characterizes most children’s stories. From Ancient Greece and Aesop to Harry Potter, there is always something to be learned in regards to values and moving through life, even in the subtlest of ways. On the flip side, there books that just present information in an imaginative way, like my very own favorite “The Very Hungry Caterpillar”, which takes me to my next point; imagination. Children’s books are called to spark children’s imagination, make think, dream, solve puzzles and mysteries or question the state of the world. It allows them to build their own worlds and see things from a new perspective. It is exciting and thought-provoking, which is, in my opinion, a books true purpose.

Now, for a little bit of history, children’s literature became a distinct and recognizable genre in the 18th century. However, long before that, the ancient Greeks had already established the importance of teaching stories to their children and having them recite long texts or even perform them. Stories and education were interconnected in the ancient Greek educational system, which was heavily based on performance. This performance consisted of two components; memorization and recitation of poems and dramas. The assigned teachers would correct the student’s pronunciation when needed and, from one point on, expect students to come up with their own stories to perform.

To quote Seth Lerer once more “The Greeks may have loved their children, but the Romans celebrated them”. An example of this is the creation of poems to celebrate Roman children’s birthdays. Stories in general, in ancient Rome, were part of the curriculum, in an attempt to prepare students for their adult civic life. Whether it was Homer or Hesiod, children would recite and take on different roles; the parent, the son, one of the twelve gods, etc.

The fact that, in ancient times, children were brought up reading and being familiar with stories, is proof of how important literature was (and still is), not only as a part of childhood itself, but more than that, as a means of entering public life and knowing how to act appropriately and according to the time’s norms.

Reference

- Children’s Literature: A Reader’s History from Aesop to Harry Potter. Brittanica. Available here