By Carmen Chang,

Having clarified the definitions of various types of artificial languages in our previous articles, it is pertinent to present some examples from these constructed language families. We will begin with a priori languages, which are further divided into paraphrasias and pasigraphies, and the latter may have a philosophical nature. These were the most successful based on logical patterns, but there are also empirical and practical ones:

“As an example of the former [philosophical], we highlight the first project for a universal system by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (Dissertatio de arte combinatoria, 1666). An example of the latter is the work Polygraphia nova et universali, ex combinatoria arte detecta (1663) by Athanasius Kircher. […] The most significant example of non-philosophical languages [paraphrasias] is Solresol (1886), by Jean-François Sudre, who based its primary elements on the seven musical notes […] These [philosophical] systems flourished in the 17th and mid-18th centuries. Examples include projects created by George Dalgarno and John Wilkins, which laid the foundation for subsequent constructed languages. However, philosophical paraphrasias can also be found in the 19th century, such as Grosselin’s Universal Language (1836) or the Universal Language Project by Sotos Ochando (1851)” (Leticia Gándara Fernández, 2017: 12-13) .

In particular, the case of Solresol, whose name means “language,” was created based on music, characterized by its antiquity and universality. Communication could occur by “singing, playing an instrument, or even with gestures.” The musical tones would correspond to the eight syllables or basic symbols of a universal language, making it easier to memorize. Its difficulty lies in its monotonous nature, but its grammatical advantage is that it facilitates word combinations: misol/solmi.

Secondly, we mention the case of constructed languages corresponding to “mixed” systems: As an example of “mixed” systems, we cite Volapük (world’s speak), created in 1880 by German priest Johann Martin Schleyer as an auxiliary language project aimed at facilitating relations between peoples. Despite initial success, Volapük soon faced failure due to the creator’s refusal to accept proposed linguistic modifications by his followers (Leticia Gándara Fernández, 2017: 13) .

It has been considered by some specialists in artificial languages as the first universal language project. Its slogan, “Menefe bal, püki bal,” meant “one language for one humanity.” Its creator, a religious figure, had an altruistic aim: to promote understanding between nations, thus breaking down cultural and linguistic barriers. Initially, around twenty-eight Volapük clubs were formed across America, Australia, and Europe, where courses were taught, diplomas were issued, and magazines were published. At its peak, it had about one hundred thousand speakers; however, at its third international congress in Paris:

“Irreconcilable differences emerged. Paradoxically, it was the first meeting where only Volapük was spoken. Its grammatical complexity, Schleyer’s claim that Volapük was “his” property, and the rise of a serious competitor, Esperanto, contributed to its downfall” (Alejandro Agostinelli, 2021).

Finally, we will focus on the case of artificial languages created a posteriori. Among all the constructed languages using a posteriori methods:

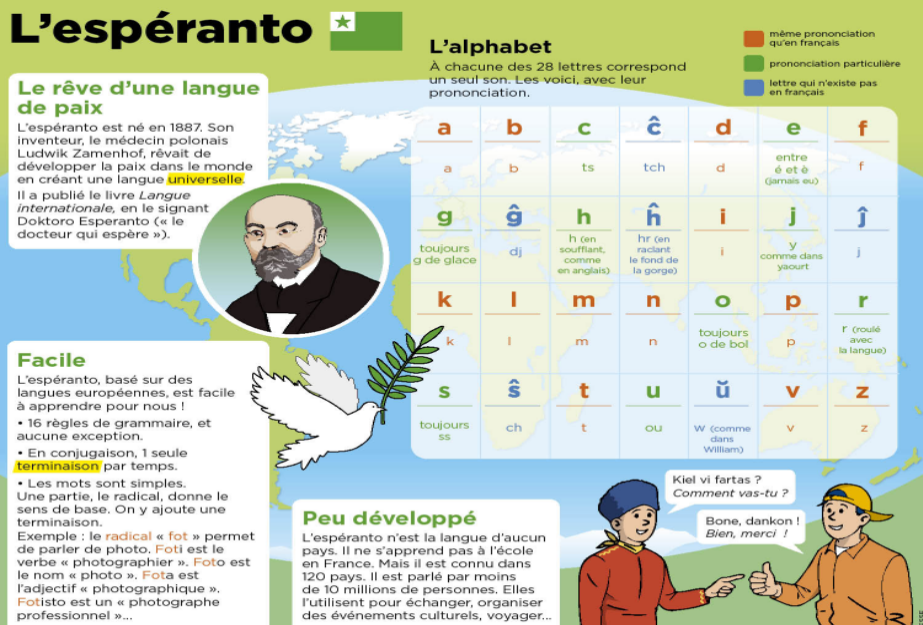

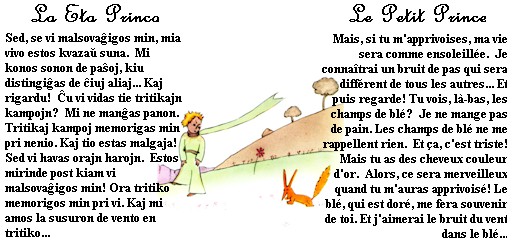

“The most well-known project is undoubtedly Esperanto. This language was created by Zamenhof in 1887 with the goal of ensuring peace and unity among peoples. To create it, the Polish linguist based it on the roots of Indo-European languages, especially Russian and Latin. The institutional and social support Esperanto has received has enabled it to become one of the most recognized artificial languages, with speakers from all around the world” (Leticia Gándara Fernández, 2017: 14)

According to Iván Olsen (2018), in his article “What is Esperanto? The Most Spoken Planned Language in the World,” Esperanto is “an artificial language that aspires to become the international language par excellence,” for multiple reasons, as it can express thoughts with great precision, it is not tied to any nation, and it is easy to learn.

“Some scientific studies have shown that Esperanto is up to ten times easier to learn than any other language […] Esperanto has an Indo-European-type grammar, simple and logical (only sixteen grammatical rules). It can generate thousands of words from a few roots. The international character of Esperanto’s vocabulary. It was extracted from many languages and adapted to the typical endings and pronunciation of this new language. Much of its vocabulary originates from Latin and Romance languages, primarily Italian and French; German, English, Russian, Polish, and Greek to a lesser extent. You can even find words from Hebrew or Japanese!” (Iván Olsen, 2018)

Umberto Eco (1932-2016), author of The Search for the Perfect Language (1994), in his interview “Esperanto and the Pluralism of the Future,” conducted by István Ertl (Universala Esperanto-Asocio, Rotterdam) and François Lo Jacomo (Paris), concluded that, although imposing an artificial language would have been impossible until then, with Esperanto, the situation could be different:

“As for me, before having clearer ideas about Esperanto, its artificial nature did disturb me, but after studying it, I could have believed it was a natural language, so that Esperanto’s artificiality weighs on its history and origin, but not necessarily on its grammar. We always think that an artificial language is a minor one, like the type ‘Me Tarzan, you Jane’; this is not the case with Esperanto” (István Ertl and François Lo Jacomo, 1996).

Once we have processed the various types of constructed languages, these have also been promoted in artistic, cinematic, and literary fields. We believe it is appropriate to mention some examples:

“Fiction literature is not alien to the movement of creating artificial languages. The linguistic theme thus plays a very important role in both the utopian stories of the 17th and 18th centuries and in the dystopian novels of the 20th century. Nowadays, constructed languages created purely for artistic purposes have taken center stage. In line with the writers of fictional works from earlier centuries, contemporary science fiction authors have found in invented languages one of the best options for creating imaginary worlds, fictitious and parallel universes in which anything is possible. An example of this is the language láadan (Haden Elgin, 1984), the elvish languages (Tolkien), or Dothraki and Valyrian (Peterson, 2009).”

“Lastly, we also highlight other projects created for other fields, such as cinema, that have gained great popularity. Examples include the Klingon language (Okrand, 1979) from the Star Trek saga and the Na’vi language (Frommer, 2005) from the film Avatar. In the case of private languages, it is interesting to distinguish between languages that are products of a culture, such as Klingon (specific to the Klingon race) or Dothraki (a differentiating feature of the Dothraki people), and languages intended to create a particular culture, such as láadan in the Native Tongue trilogy (Leticia Gándara Fernández, 2017: 14-15).”

In conclusion, the motives that inspired the inventors of these artificial linguistic codes or systems present their particularities, and it is easy to see their different perspectives and visions depending on the prevailing mentality of each era, discipline, and academic, artistic, or scientific field. In a constant search for a language characterized by its harmony, beauty, and perfection, this difficult linguistic project has not received the importance it deserves. In fact, to date, the history of artificial languages has not met the success expected by their inventors. As Umberto Eco (1994: 28, cited by Leticia Gándara Fernández, 2017: 15-16) remarked: “Although it was the history of invincible obstinacy in pursuing an impossible dream, it would still be interesting to learn about the origins of this dream and the reasons it has remained alive through the centuries”.

References

- 7 lenguas artificiales: la imaginación tiene la palabra. Yahoo Noticias. Available here

- Ertl István et Lo Jacomo François. “L’espéranto et le plurilinguisme de l’avenir. Entretien avec Umberto Eco”. Universala Esperanto-Asocio, Rotterdam, 1996. p. 24/27.

- Gandara Fernandez Leticia. “Origen y evolución de las lenguas artificiales”. Revista Tonos Digital. V 33, 24 de junio de 2017.

- ¿Qué es el esperanto? La lengua planificada más hablada del mundo. Infoidiomas. Available here