By Mariam Karagianni,

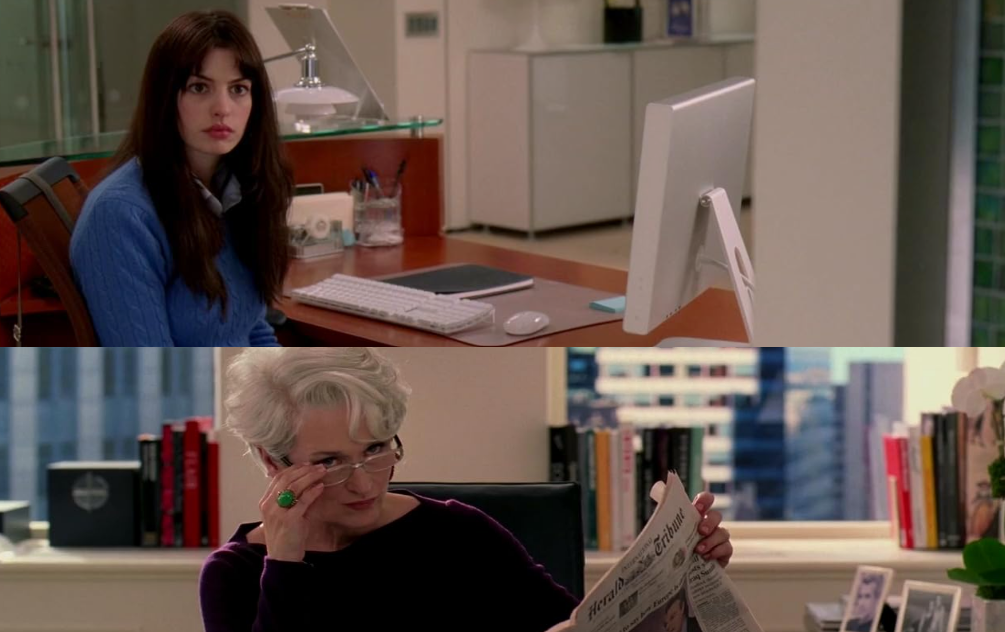

If you’ve seen the movie The Devil Wears Prada, you remember Miranda Priestley’s (played by Meryl Streep) iconic speech on the cerulean sweater Andy wore. In particular, she said, “…You’re also blithely unaware of the fact that, in 2002, Oscar de la Renta did a collection of cerulean gowns, and then I think it was Yves Saint Laurent, wasn’t it? Who showed cerulean military jackets?” Indeed, there was a period in the fashion world when designers inspired other designers, and the influences on the runway derived from within. But now, as fashion trudges through this tyranny of algorithmic approval, it sets the question of whether personal style is something of an extinct species and if the art of craftsmanship has been impaired permanently.

Why is it that people consistently dwell on the refined and timeless elegance of Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy’s style? What makes the likes of Jane Birkin, Jacqueline de Ribes, and Anna Piaggi stand out from this plethora of well-dressed people? You’ve guessed it. It’s the strong sense of personal style, a confidence that leaves others curious as to whether they want to be the person in question or follow them around and steal awed glances at them. As Iris Apfel said, “Style is something inherent. You must know who you are first and proceed from there, and that’s a lot of work that most people want to avoid”. To put it simply, it does not require renewed couture wardrobes but simply the existence of good taste.

Unfortunately, it seems that day by day the essence of personal style is hanging by a thread in this digital playground of performative aesthetics, in which Pinterest boards, Instagram feeds, and our TikTok For You pages guide us into wearing the same trite microtrends. People, and especially the younger audience, try to find their personality in their style as opposed to finding their style in their personality. This is why the outfits put together as a result of this have a rather cosplay-esque vibe; and TikTok’s obsession with “core” and coring everything (whether it’s Barbie, being a coastal grandma, or living in a cottage) does not help at all.

Don’t get me wrong. Trends (and their ephemerality) are not derivative of social media. They existed 24 years ago when everyone was obsessed with Juicy Couture tracksuits, they existed in the 70s when flared jeans took over the market, and even in the Middle Ages when women would chalk up their faces to appear pale. They are a natural part of the fashion cycle, especially for such visual and nostalgic beings as humans are. But with the quarantine of 2020 and the rise of TikTok’s prominence, trends (and especially microtrends whose lifespan lasted a few scrolls down the FYP page) became just another source of content creation. There’s no logical sequence between the emerging aesthetics; if anything, it seems like we swing from one direction to the other violently. How does, for example, the clean-girl Matilda Djerf aesthetic replace itself with the dark-feminine mob-wife core that emerged right after? Well, it’s easy to know why once you realize that those trends that tend to nothing but a one-day virality chance on the platform find their roots in consumerism and pay no genuine homage to any subcultures behind it.

And who’s a better architect of fleeting obsessions than your average influencer? It’s been noted, as dictated by the behavior of many brands, that they are not really looking into people who have a distinct sense of fashion. Rather, they prefer those who are far more basic in their sartorial choices, as they represent a blank canvas, making them malleable for those brands to commercialize and monetize. Keeping this in mind, perhaps the problem isn’t even bad or repetitive style. It’s the complete nonexistence of it. And the continuous exposure of young adults to this interchanging succession of aesthetics deters them from finding sartorial stability.

But the fashion houses, the grand Maisons of craftsmanship, are not unaffected by this. David Graham, back in 2012, wrote that fashion critics have been lessened and replaced with bloggers who were untrained in the art of criticism. And a decade ago, no blogger had the following or the influence an average TikTok star has now. The coveted front rows are no longer a space for editors, buyers, and acclaimed celebrities draped in the industry’s cultural lexicon. The backstage of runways is not just for designers, models, and makeup artists but also for filming GRWM videos, TikTok dances, and awkward, staged interviews.

When once John Galliano would look at 18th-century French history and Rococo art to get inspired for his 2000 Spring/Summer collection at Dior, Miu Miu looked at the countless “Black Swan” edits and the rise of balletcore for their 2022 Summer/Spring collection. A fashion executive once told Cathy Horyn, “When you think of young designers launching their own brands, it’s been a long time since we’ve been shocked, thinking, wow, there’s a new designer coming”. Even with Coperni’s innovative spray-on dress on Bella Hadid at the 2023 show in Paris, controversy arose as to whether that was a sartorial novelty or a publicity stunt aiming for marketing virality.

At the end of the day, despite the aforementioned, it’s wise to remember that the fashion industry is quite a sanitized space, and establishing even the slightest credibility has turned into a Herculean feat. Perhaps, the infiltration of such an ivory tower is not inherently bad if approached thoughtfully; it could push the industry’s boundaries and force it to leap forward with novel concepts and other ways of connecting with their audience, promoting more inclusivity. But the key point is that the answer to your next clothing choice does not lie in the next viral aesthetic that will pop up on your feed; it’s within yourself. By all means, take inspiration from the web, but try to experiment with that vision by using other colors and textures that attune to your personality. Do that unapologetically, without the need to conform to online validation, as your wardrobe should not be a chronological accumulation of passing trends but your intimate celebration of your individuality.

References

- Lost in the Machine. The Cut. Available here

- Fashion Week: The beleaguered art of fashion criticism. The Star. Available here