By Dimitris Kouvaras,

History can be many things. The most common of its perceptions is, perhaps, that of a continuous narrative in a schoolbook, often excruciatingly difficult to memorise in its innumerable details. However, such an isolated image obscures rather than illuminates its actual dimensions, even in its context as a science.

Suffice it to say, besides a scientific discipline, “history” generally conceived can encompass or relate to different types of narratives or representations of the past, from medieval legends to national celebrations. In this article series, I will delve into history based on a basic epistemic distinction, encapsulated in two latin terms: res gestae, i.e. past events, and historia rerum gestarum, i.e. writing about past events. Both aspects of reference to the past are interlinked and have diachronically shaped our views and interpretations of it, consciously or not. To better understand the formation of history as a concept signalling a process of past events and, by now, a scientific discipline, I will be looking at it through the lens inherent in the term itself: time. In other words, I will be examining what is known as historiography: the study of how history has been written and, at a later point, how it reflected upon itself throughout time.

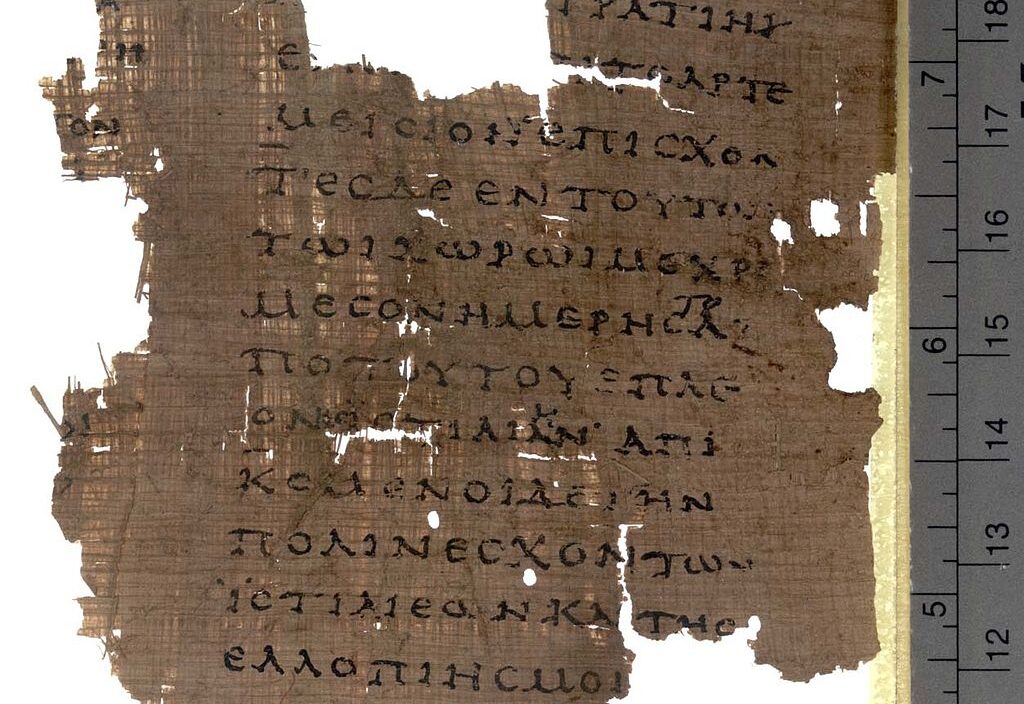

The first rudimentary forms proximate to historical writing originate from the ancient Near Eastern civilisations, such as the Egyptian, the Assyrian and the Babylonian. No coherent concept of history had yet emerged, although the need for the establishment of continuity through time, corresponding to bureaucratic, dynastic and, also later, literary purposes, is evident through the surviving kings’ lists, inscriptions, annals –collections of references to wars and other important events–, and chronicles, even in the third person. However, such “chronographic” texts, involving sequences of events situated in time, lacked consistency and, in the case of chronicles, factual backing. In the Hebrew Bible, the Tanakh, written in the first millennium BCE, by contrast, one finds a continuous narrative of Israelite history towards a divinely devised end, which contains some information that can be deemed historical and a clearer conception of time as a field where (the Israelites’) God’s will unfolds. Nevertheless, its religious character precludes its classification as historical.

The Greeks are the ones most often credited with the invention of history. However, as we saw, history is not something that can be invented at once or appear out of the blue. What can be said is that ancient Greece had a strongly developed historical culture, a certain sensitivity towards the notion of time as an organising axis for narratives, already from Homer’s epics and Hesiod’s Theogony. Herodotus’ Histories (which meant investigations at the time) is considered by many the first proper historical work, in the sense of a concise narrative of the past written by a distinctive author. In it, Herodotus traces the history of Graeco-Persian relations from its mythical origins to reach an explanation of recent Persian Wars while embarking on extensive ethnological, geographical and anecdotal references. Synthesised through the material he collected in his travels, the Histories involve a first attempt, although basic, to ascertain the truth of what is written. Nonetheless, Herodotus is anxious to include material from dubious sources and references to myth, which could be explained given the fact that the work was intended as a source of pleasure for the reader, a charge made by Thucydides.

The latter is stereotypically known, at least in Greece, as the first “scientific” historian, despite the blatant anachronism of the statement. It is true that he refined the methods of Herodotus concerning truth-finding and excluded supernatural causes, while employing a nuanced distinction between pretextual and actual causes of events, but he included numerous speeches in his work, which he admits are his own synthesis and aim at reproducing the gist of what was said without necessarily being true to facts. His ideological partiality has also been challenged to a degree. Unlike Herodotus, who writes an ecumenical history, Thucydides focuses on the political and military history of his contemporary Peloponnesian War, which he intends as a “possession for all time”. This points to a cyclical conception of time by the ancient Greeks, who believed in the existence of patterns and immutable elements in human behaviour. Another crucial element in their thought was that of Tyche, which means fortune and was believed to influence the fate of historical subjects.

In the Hellenistic period, under the influence of Isokrates, history and its genres became tied to rhetoric and persuasion took precedence over the conveyance of verified facts. Meanwhile, the globalised world of Alexander the Great and his successors created new imperatives for historical writing, which undertook the task of explaining such an interconnected reality. This trend continued in Roman times. The Greek historian, Polybius, who had witnessed the fall of Carthage and the rapid spread of the Imperium Romanum, is especially noteworthy. Having Thucydides as a role model, he set to write a universal history of Roman expansion emphasising in ascertaining the truth of facts. It was a political and military history of great men, intended to convey policy lessons through time. History became didactic, still in a framework of cyclical time, with Latin Tyche, or its Latin counterpart Fortuna, as a governing factor. In the Roman era, the concept of history, as a narrative on the past, was crystallised for the first time, while time was, by some historians, seen as a vehicle of decline rather than progress.

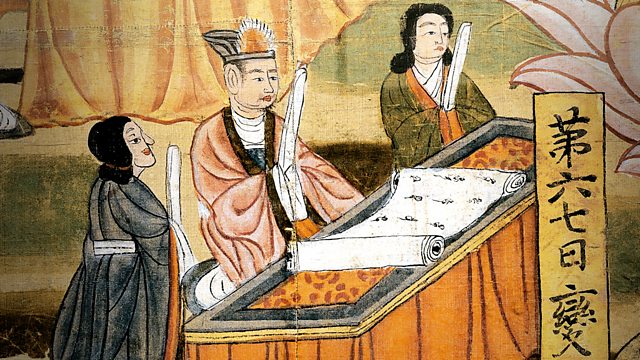

Of course, any analysis of ancient historiography would be incomplete without reference to China. Often omitted due to a Western-centric approach to history, Chinese historiography effectively matches the Greek one in terms of antiquity. However, its conception of time is entirely different. Time in ancient Chinese thought was an actor of change rather than the vessel in which the latter happens, while distinct periodisation was preferred over tracing time to its origins. The annal was considered not rudimentary, but the highest form of writing, as a distillation of the most important aspects of sources. Tradition played a crucial role, and direct copying of esteemed sources was not treated as indolence, as often was in the West, but precision to the truth. The writing of history was intertwined with the Confucian doctrine and the needs of imperial bureaucracy, which was its primary source, unlike the distinct historian personas of the West.

Ancient historiography shows how diverse human conceptions of time can be, as well as how the elements composing historical thoughts varied from time to time and from place to place. Above all, though, it is a testament to how people were always actively engaged with the past. With the advent of Christianity, its conception would take a completely novel turn…

Reference

- Woolf, Daniel. A Concise History of History: Global Historiography from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.