By Mariam Karagianni,

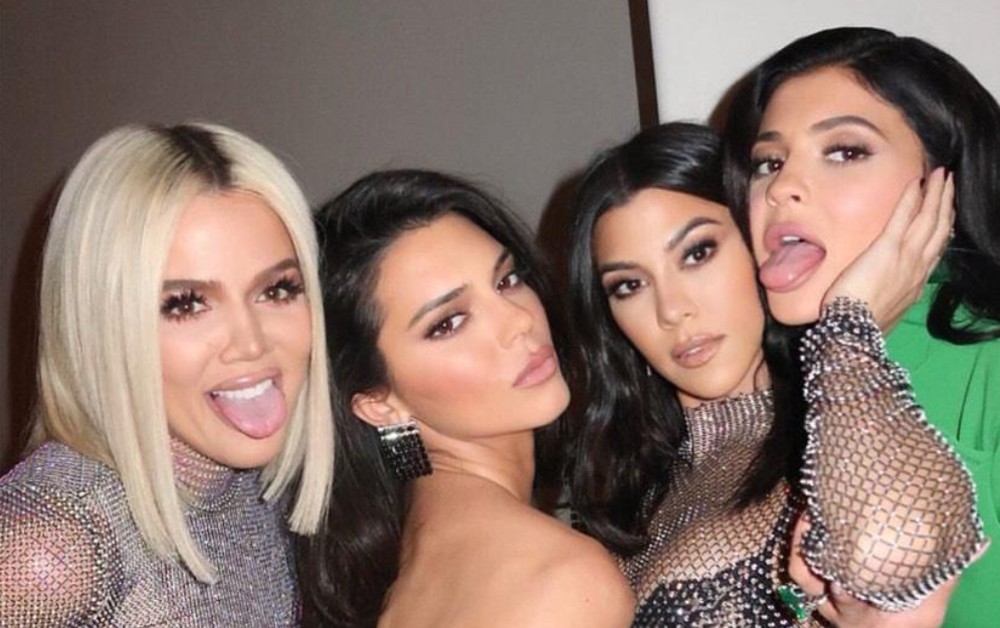

A perfectly chiseled nose. Overfilled, glossy, plump lips. High, almost elfish cheekbones. Cheeks without buccal fat. Lifted, foxy eyes. A pair of enlarged, perky breasts. A small, defined waist. A voluptuous and round backside. Endless long locks of extension hair. Do any of these terms sound familiar to you, or did reading them make you feel dizzy? If you’re struggling to decipher them, simply open Instagram to any influencer’s page, and you’ll notice that unless you recognize a specific one, they all look almost identical. Influencers, reality show personalities, models, and actresses —it doesn’t matter who.

In 2019, Jia Tolentino, in her New Yorker article, described this phenomenon as “The Age of Instagram Face.” In other words, it’s the emergence of a single, cyborgian face that women of all ages are actively mimicking. Tolentino discusses how women in today’s society are dooming themselves to a globalized, boring sameness. “Young women”, she writes, “try these procedures like clothes in a dressing room”. Almost five years later, this passion for everyone to look like watered-down versions of Kim Kardashian seems even more fervent. What once seemed like a simple anti-aging routine has transformed into an extensive and meticulous indoctrination about how even the most minor habit (e.g., drinking from a straw) can cause wrinkles. Plastic surgeons and aestheticians take advantage of a girl’s natural insecurity and subtly demonstrate that the ideal feminine beauty is only attainable through painful processes of physical manipulation.

The truth needs to be told: Botox makes young girls look old. And it’s not in the sweet, old-lady-handing-out-candy way, either, but rather in a bizarre phenomenon where younger and older women have started to look alike. It’s the homologous result of all ages getting the same work done to their faces, making it difficult to tell whether a woman is 24 or 44 years old. Injectables like Botox were originally created for women in their 30s and well into their 60s to eliminate existing wrinkles. But younger women were sold on the idea of preventative Botox, which ironically backfired.

But why are women so willing to drastically modify their natural features, even when the alteration does not suit them? It’s quite simple: we live in a hierarchically structured society in which the quest (and not just the attainment) of beauty is very much rewarded. In fact, it’s rewarded so highly that it almost converts to a form of currency. Remember the phrase “pretty privilege”?

All these surgical habits ultimately aim to reaffirm the archetype of the “ideal woman.” In her book, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion, Jia Tolentino defines the ideal woman as “someone conceptually overworked, an inorganic thing engineered to look natural. She steps into a stratum of expensive juices, boutique exercise classes, skin-care routines and vacations, and thereby happily remains.” The paradoxical femininity that society promotes is based on a highly refined, curated lifestyle. It involves time-consuming wellness routines and an exhausting engagement with one’s physical appearance, which only gets praised if the work done is invisible—natural and effortless. Otherwise, it’s considered vulgar and cheap. This creates a class division between women who can afford all of that untraceable work and those who can only attain a mimicry of it, which often ends up looking artificial. But women in both groups are actively manipulated into enduring these procedures with a smile on their face.

“Beauty requirements have escalated as women’s subjugation has decreased. One waste of time has been traded for another,” writes Naomi Wolf in The Beauty Myth. There is a deep, patriarchal logic embedded in our society that drives women to continually strive for higher levels of prettiness, as if compensating for no longer being legally or financially dependent on men. It’s a reshaped form of pressure, where the expectation of dependency has been replaced by an intense emphasis on appearance. Today’s mainstream liberal feminism has not eradicated the stronghold of the ideal woman but has instead aligned itself with it.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, yes. And the body acceptance movement, which values beauty in every shape, color, and age, and diversifies a previously predominantly white and thin industry, is truly a positive step forward. But it’s also double-edged. It’s wise to remember that this wave exists in a society where beauty is still of paramount importance. There’s even a moral —even political, I’d say—pressure to acknowledge everyone as beautiful, to allow anyone to infiltrate the beauty standard boundaries, and mold them around themselves to gain that “safety umbrella,” giving their lives a sense of meaning.

It’s quite sad to see that there have been few efforts by Western feminists to de-escalate the significance and imperativeness of beauty; to state that it’s not every woman’s life-long goal to affirm herself in this dystopian and obsessive cult of physical appearance. And even fewer have attempted to avoid conforming their branch of feminism to the same patriarchal and capitalistic structures that led to all this. While they may not encourage old habits under the same names, they have simply rebranded them: beauty work is now labeled as self-care and investment, which sounds progressive, doesn’t it?

Technology, on the other hand, not only meets the demands of the beauty market but greatly exceeds them, beyond imagination. Yet, it is used very little in researching why, for example, hormonal birth control pills have such negative effects on women globally, though this is a significant concern in gynecology. Issues like neglected childcare systems, wages, lost political representation, and gender-based violence are swept under the rug. And while achieving parity and justice in these areas seems an unthinkable concept, we’re assured it’s all well, because, after all, we have maximized our capacity as market assets by 101%. Why should mainstream feminism even bother to address any of the aforementioned, when it can market a brand new influencer for us to copy their looks?

References

- The Age of Instagram Face. The New Yorker. Available here

- Jia Tolentino. “Trick Mirror; reflections on self-delusion”. HarperCollins Publishers, 2019

- Naomi Wolf. “The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women”. Chatto & Windus, 1990