By Carmen Chang,

The “simplification” and “universalization” projects, typical characteristics of constructed languages, present a significant disadvantage, as they threaten the survival of historical languages, which are defined by the ancestral traditions of their speakers and constitute a historical legacy. Through these languages, each society shares its view of the world:

“This destruction in pursuit of supposed “simplification” follows absolutely petty political criteria: lack of funding for education; “ease” practices in educational plans that lead to the “elimination of foreign languages” (except English, of course) instead of adding indigenous languages to other foreign languages, even non-traditional ones; lack of awareness of new scientific findings in psycholinguistics that prove the human brain develops more cognitive abilities the more languages it learns. If the human species were to become monolingual, our brain would be affected and might lose part of its innate linguistic creativity (according to some psycholinguists)” (Silvia Helman de Urtubey, 2002: 2-5)

One of the greatest flaws of artificial languages is that they would encourage a simplified, unified, and monotonous way of thinking, which disregards the importance of linguistic diversity and human creative capacity. However, it cannot be denied that one of the dangers of natural languages comes from the shame and disrepute they generate among new generations regarding the preservation of indigenous and aboriginal languages:

“In Santiago del Estero, my homeland, the Quechua language has almost entirely disappeared as a spoken language, due to deculturation and the “contempt” for anything non-Hispanic (or European, at best). What is indigenous was (and for many still is, unfortunately) synonymous with “unculture, poverty, marginalization” “(Silvia Helman de Urtubey, 2002: 2-5)

On the contrary, speaking other languages promotes access to the most recent academic and scientific studies, as primary sources of knowledge. In this sense, this intercultural communication would facilitate “dialogue between cultures,” as it allows knowledge to be transmitted through discourses and sociocultural practices:

“In today’s world, the revolution of communications and the immediacy of information makes the need for “first-hand” communication increasingly important, not through translations or interpreters, who are not always available when needed and are not always guaranteed to be faithful to the author’s thought’’ (Silvia Helman de Urtubey, 2002: 2-5).

Moreover, learning various languages would improve our communicative competencies and facilitate intercultural understanding and the comprehension of different worldviews —something the inventors of artificial languages overlook:

“Studying a foreign language means, of course, acquiring basic communication competencies: reading, writing, speaking, and understanding both written and spoken interactions. But it is much more than that: it is approaching another culture, grasping a different way of seeing the world, engaging with texts, authors, and different ways of thinking, not —as some believe— with the intention of copying foreign models, submitting ourselves, or being “colonized,” but, on the contrary, with the intent to understand diversity, “otherness,” as some say, through a critical reflection on our own language-culture, that is, through our identity” (Silvia Helman de Urtubey, 2002: 2-5)

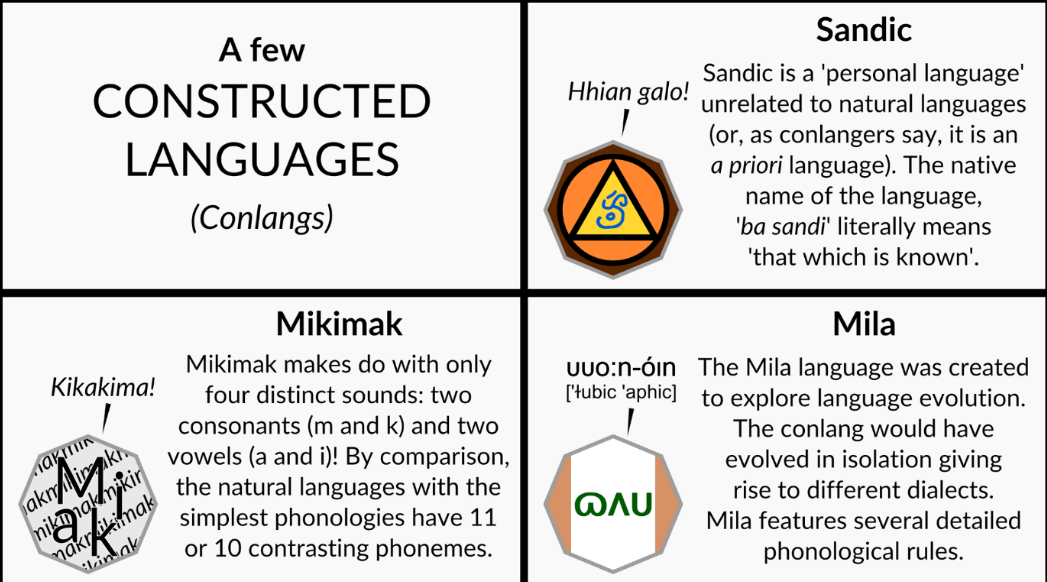

On the other hand, the failure of artificial languages lies in the fact that they are constructed languages that do not form part of the historical and linguistic heritage or the national identity of a people or society. They have been constructed from the perspective of one person or organization, which does not represent the speaking community of a territory and, therefore, does not meet regional needs. To these disadvantages, we can attribute the failure of constructed languages, especially those a priori, which, due to their scientific and philosophical nature, are not widely accepted due to the difficulty of their symbolism:

“In terms of practical use, a priori languages proved to be a complete failure. The main problem was that the natural boundaries between concepts, which were supposed to be determined by “science” or philosophy, proved to be elusive. The boundaries between the concepts agreed upon for the artificial language turned out to be no less arbitrary than those of conventional languages. Secondly, an a priori language required a prodigious memory for symbols. Learning the thousands of symbols necessary for such a scheme is a daunting task that few attempted or even succeeded in. By the 19th century, the idea of an a priori language was no longer in fashion” (Esperanto Kolombio, 2018)

As a result of the difficulties with a priori artificial languages, a posteriori linguistic systems emerged, whose grammar is more easily comprehensible as it resembles traditional languages:

“Artificial languages that have a pattern based on real languages —with phonemes, morphemes, words, and phrase patterns—belong to the second type of artificial languages, called a posteriori languages. These are real languages with grammars that follow a simplification pattern from existing languages” (Esperanto Kolombio, 2018).

In the case of a posteriori artificial languages, one of the main challenges is that, although they typically stem from the Indo-European linguistic branch, they are still difficult for many adults to learn:

“A person’s mother tongue is part of their identity and cultural heritage, something that is not willingly abandoned. Therefore, it is unlikely that an artificial language, lacking cultural prestige, would replace living, natural languages. Even if an artificial language were adopted as a global language, each nation would eventually develop local dialects based on the interference of their own mother tongue; these would eventually begin to diverge into separate languages, just as creoles based on English and French have in many parts of the world. There have even been riots among Esperantists. At the beginning of this century, a dissident group created Ido, a simplified version of Esperanto” (Esperanto Kolombio, 2018).

In reality, artificial linguistic projects could be useful in academic, scientific, and even entertainment fields because their learning is deliberate and requires certain aptitudes, knowledge, and complex linguistic skills. For this reason, they could not be adopted by the entire international community, and perhaps the most feasible option would be the use of lingua franca, which are considered the primary means of universal communication:

“Instead of using an artificial language as an international lingua franca, the world community seems to be moving toward the use of several widely spoken languages as lingua franca in different parts of the world. Mandarin Chinese has over a billion speakers. Hindi has almost the same number. Then come English, Spanish, Russian, and Portuguese. These languages, along with French, German, Japanese, and Arabic, can be used to communicate with the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants. Today, English is the closest language to being a global international language: more people speak English as a second language than any other language. Chinese and Hindi are primarily spoken in South and East Asia” (Esperanto Kolombio, 2018).

References

- Lenguajes Artificiales. Esperanto Kolombio. Available here

- Silvia Helman de Urtubey. “Globalización: ¿Empobrecimiento lingüístico o plurilingüismo enriquecedor?”. La Revista. n(4), 2002.