By Dimitris Kouvaras,

Since Putin invaded Ukraine in 2022, an undeclared war has been underway between Russia and the West. NATO is supplying Ukrainians with munitions and wartime technology. In parallel, sanctions have been imposed to starve the Russian economy of oxygen, and exclusion from international cultural events to challenge its parity in terms of political civility. Russia, on the other hand, fosters sabotage and propaganda to meddle with European arms production and American election results, attempting to alleviate military and diplomatic pressures and undermine its foes. The result is an alarmingly destabilized situation.

However, in the case of Russian-West relations, that is hardly a new thing; a macrohistorical perspective proves that tentative, if not directly, hostile relations between the West and Russia have been the rule rather than the exception. This begs the question of what sets these worlds apart and, most importantly, whether convivial relations can be achieved. Scoping events across the centuries may hint at answers, concerning the specific international relationship.

Our gaze through time will bring us back to the 15th century, when the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, the predecessor of Russia, established itself as a local power against the Mongol khanate of the Golden Horde, starting to incorporate competing Russian statehoods along the way. Bound geographically by the open planes to the West, and steppes to the east, it faced the threat of invasions by the immense Poland-Lithuania, on the one hand, and nomadic people on the other. To withstand the pressure and avoid dismemberment, Russian rulers from the 15th to the 17th century transformed agrarian, nobility-based Muscovy into an autocratic bureaucracy capable of participating in the European power diplomacy of the time. Non-isolation and centralization were the recipes for survival against a powerful, but incohesive, Poland-Lithuania and fearful but scattered Mongols. Therefore, Russia was forced to enter a dialectical relationship with the West from its inception. Soon, ties would grow even closer, but not necessarily stronger.

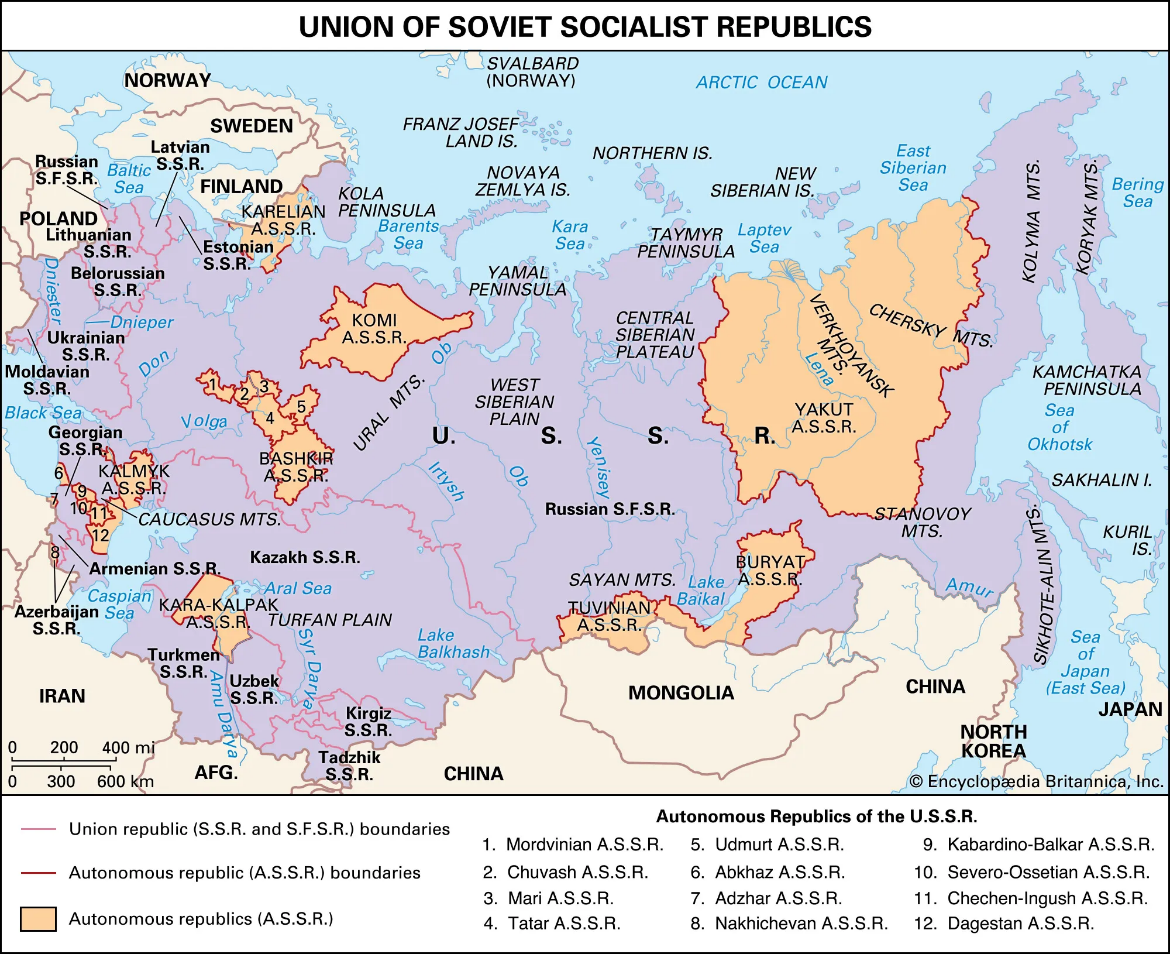

The 18th century brought an empire for Russia, in both name and form. In the first half, Peter I and Catherine II in the second ensured a great legacy by creating a greater Russian Empire incorporating Baltic, Polish, Ukrainian, and Caucasian territories. However, to become a great power Russia had to look like one, which meant modernization. Peter I created the sumptuous imperial capital of St. Petersburg, imported Western courtly fashion and trained professionals, and forged a Russian navy. Likewise, Catherine II expanded the country’s military capabilities and enhanced her legitimacy with a veneer of enlightened reforms. However, Western emulation as an empire-building tool never reached the bulk of agrarian Russian society, living under serfdom, and enhanced rather than mitigated Tsarist supremacy. Only England followed a constitutional path then, so Russia was no exception. But not for long.

The aftermath of the French Revolution, and the Vienna settlement of 1815, might have consolidated Russia as a great power (the Tsar was after all the leader of the so-called “Holy Alliance”) in diplomatic parity with Britain and France, but the liberal ideas and industrial production spreading in the West singled Russia out as backward. For the Western bourgeois imaginary, it was a quasi-civilized land, an antiquated feud. Efforts for reform, fatally contingent on tsarist personalities, did little to change that. Only by the late 19th century did Russia enter a path of urban industrialization through French investment and conceded some social freedoms.

Politically, it remained an autocracy, which is understandable given how dispersed and multinational its population was. Russia was, therefore, in many ways part of the West but also different. Their relationship was tentative, and alignment occurred only in the face of great geopolitical common danger, as the First and Second World Wars would show. Contrarily, in the 19th century, the Anglo-French didn’t hesitate to scold it in the Crimean War when it interfered with their eastern interests.

The First World War was a turning point. Russia entered a sworn Entente (great) power with ambitions on Constantinople and left a compromising rebel. Amidst severe economic disruption, food shortages, defeat, and foundering morale neither the tsarist nor the parliamentary Provisional Government of March 1917 acted on the social demand for ending the war by remaining committed to the Entente, i.e. the West. Thus, in November 1917 the radical Bolshevik element (a minor socialist faction with Lenin as a charismatic leader) took power and held on to it by promising and delivering peace, at the loss of most imperial territory. That was done to the dismay of European powers and the recently added but growing United States.

Tsarist generals (the “Whites”) with support from constitutional elements took to an incohesive counteroffensive from the Russian periphery with imperial borders in mind. They received military support from the Allies, who feared a westwards revolutionary wave –desperately promoted by Bolshevik propaganda– and despised Bolshevik illiberalism, in an undeclared war whose diplomatic duplicity oscillated between backing eastern European and Baltic nationalisms and resurrecting Russia intact as a bulwark to defeated yet fearful Germany.

In 1919, it was difficult to see shrunken, bankrupted, and civil-war-ravaged Russia as a great power. Instead, Allied intervention treated it as a malleable power vacuum, where Bolshevism, seen as a political anomaly breeding on wartime privation, would be liberalized through food relief or vanquished by force, and tsarist generals would supervise a constitutional reconstruction. Both estimations misjudged Russian reality and had the Allies trying to mold Russia into Western political standards with an incohesive quasi-imperialist policy that made compromise impossible. On humanitarian grounds, isolating Soviet Russia by effectively denying its great power status made sense due to Soviet totalitarianism and civil war atrocities. In terms of balance-of-power diplomacy, it made none.

With the Russian question unsettled by the Versailles Peace, leaving the borders of Eastern Europe undefined, numerous minor conflicts broke out, such as the Polish anti-Bolshevik crusade in 1921. Soviet Russia was estranged from the Allies and rapprochement with Germany came in 1922. When Lloyd George re-initiated trade relations with Russia following the Whites’ defeat, it was too late to reverse distrust towards the West, which aggravated interwar instability and led the Soviets to a secret pact with the German Nazis in 1939. Hitler’s foolish decision to attack Russia saved the day.

As the resumption of Allied-Soviet diplomacy starting in 1924 showed, ideological differences didn’t take precedence over power politics when Russia was consolidated and a common interest with the West existed. This was remarkably proven in the Second World War, whose end found Churchill, a fierce Bolshevik critic in 1919, sitting alongside Stalin, whose government meant terrible suffering for many Russians. Convivial, however hostile, relations continued in the Cold War, where a pragmatic approach to Russia, tolerating the U.S.S.R.’s territorial resurrection of (an expanded) Russian Empire with diplomatic contact and U.N. membership while creating NATO as a counterweight, averted European war.

Since 1991 Russia democratised and shed its imperialist buffer zone. Both were illusions dispelled in the face of Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer who exemplifies the resurgence of autocratic and expansionist drives in Russian politics. The West didn’t learn the lesson of 1919, with NATO and Western-influenced liberalism expanding eastwards with superfluous self-assurance, believing Russia (supposedly “democratic” and territorially shrunk) would acquiesce. It did not, as the war in Ukraine tragically proves. When strategically underestimated by the West, “the bear” still roars. Perceived agitation –even purely political– in its neighborhood is met with force, with the intermediaries paying the price. I believe history is enlightening, but conclusions are yours to draw.

References

- BUSHKOVITCH PAUL. «ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΡΩΣΙΑΣ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗ, ΟΙΚΟΝΟΜΙΑ, ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ, ΘΡΗΣΚΕΙΑ, ΤΕΧΝΕΣ ΚΑΙ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΕΣ ΑΠΟ ΤΟΝ 9ο ΑΙΩΝΑ ΕΩΣ ΤΗΝ ΠΕΡΕΣΤΡΟΙΚΑ». ΑΙΩΡΑ. Athens. 2016.

- Darwin John. :Post Tamerlan”. Patakis. Athens. 2017.

- Marks Sully. “The Illusion of Peace: International Relations in Europe 1918-1933″. St. Martin’s Press. New York. 1976.

- John M.Thompson. “Russia, Bolshevism, and the Versailles Peace”. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. 1967.