By Mariam Karagianni,

Conversations about mental health and people that were likewise ill used to be a taboo in older societies. This new wave of openness about it is pretty much a congratulatory moment, as the irreversible stigma attached to it was somewhat reduced. Unfortunately, this shift was not delivered without its shortcomings. Open your TikTok app and search the hashtag #sad, #depressed, or #mentalhealth. The chosen songs, the blatant misinformation, and the carefully curated Sofia Coppola/Mitski aesthetic make it look like a perfume commercial, and not the abnormal reality of an actual person.

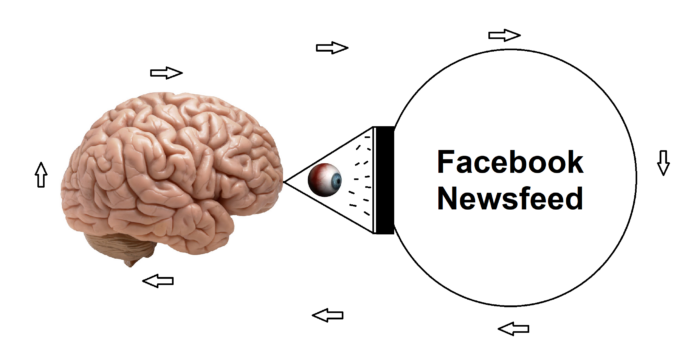

In Sapiens, Yuval Harari touches on the subject by saying that individuals are born with certain biological baselines for happiness, which obviously differ from person to person and can be affected by factors such as genetics, wealth, relationships, circumstances, and our daily influences. As far as the last one is concerned, a favorite example to bring up is the infamous “Facebook Emotional Contagion Experiment”, conducted in 2014 by A. Kramer, J. Guillory, and J. Hancock.

The premise of the experiment was the notion that emotions can be spread from person to person just like a disease. Thus, they wanted to test if overexposure to positive/negative media altered the user’s emotional state, even if that happened from their device’s screen and not an actual interaction. In a week-long period, the Facebook feed of 689,000 people was manipulated, with some getting more positive content, while others’ emotionally negative content was increased. The changes, while not drastic, were statistically significant, as it was concluded that depending on the consumption of the media, it was entirely possible for it to dictate our emotions.

Now, imagine the effects of social media a decade later, when it’s more prevalent than ever. When a young person opens their TikTok and comes across a video titled “Signs you have…” (enter the illness of your choice: ADHD? Anxiety? Depression?). The so-called indicators are, of course, a series of repeated generalizations. These can apply to a large group of people and also sound utterly ridiculous. How is listening to a song on repeat a sign that I have OCD? Maybe I just like the lyrics.

Through this very vague online behemoth, the creators’ aim is for their misinforming posts to perform well through relatability, making them shareable, but not at all informative. But a young adult’s mind absorbs this presented information and takes it as gospel. Remember how the Tumblr era of diet culture and eating disorders affects people until now? That wasn’t even as widespread an app as TikTok or Instagram. And it’s a given, unfortunately, that the reduction of mental illness into a merely quirky trend will strain the new generations for many years to come.

If you think that romanticization of an illness is a trait millennials and Gen Z are to blame for, you’d be widely inaccurate. In the 19th century, tuberculosis was often depicted in literature and art. The symptoms of it (fatigue, weight loss, coughing up blood) gave an air of physical fragility and noble suffering that was linked to many famous poets and writers suffering from it. Thus, it added more to the trope of the “tortured artist”. On top of that, the so-called “faded flower” aesthetic was desirable, as young women purposefully tried to appear thin, frail, and pale.

But what is the cause of the obsession with appearing ill, whether that’s physical or mental?

Nietzsche has his explanations. In Genealogy of Morality, he explains that individuals are not born with a set of morals. We do not punish someone just because our moral compass tells us they are a bad person. In fact, to label someone as deserving of punishment is a far advanced concept, for which we need to intellectualize that they intentionally committed a series of actions that are deemed wrong.

While it had been an ancient habit to display torture as entertainment in history (e.g. gladiator fights or French Revolution executions), as we entered civilized society, to afford peaceful coexistence, those cruel pleasures had to be subdued. This was the root of guilt: people became ashamed of their primal instincts and thus turned this torture inward. Therefore, the cruelty that satisfies us now is the one we inflict on ourselves.

Abrupt as that sounds, the psychology behind it is fascinating. Sadness and suffering are inevitable parts of life, and causing that to ourselves gives us a sense of control over the pain. Call it self-mastery, if you like. Also, there’s moral value attached to feeling guilty and shameful, which makes us, in consequence, feel like good people. Thus, there’s a meaning to it. As Nietzsche mentions in the book, “the meaninglessness of suffering, not the suffering, was the curse that lay over mankind so far”. So as long as there’s reasoning behind suffering, all is good.

For someone that doesn’t know anyone with a mental illness in real life, a movie will play a decisive role in how they perceive it. But to make the movie appealing to a younger audience, the execution must fall within certain aesthetic expectations: attractive cast, a romantic interest, interesting plot, and memorable (if not quotable) lines. All this is quite unrealistic and takes away from the seriousness of the topic.

At the same time, this provokes a certain desire in the mind of the young to want to experience this aestheticized depression (and such), because it gives them a mentally complex persona with deep insights on life —quirky personality traits that will make them stand out amongst their peers. As if being happy and healthy makes someone boring and ignorant of life’s harsh realities. Because of this, they choose to consume sad and vulnerable art, as only that feels authentic and intellectual.

There’s a safety in knowing who we are. People are motivated to constantly experience emotions that confirm and add to their self-concepts, even if they’re negative. Even if sadness is not a constant in one’s life, listening to sad music when one is gloomy encourages the said feeling, and even induces a sort of subconscious masochistic pleasure. Or perhaps, this romanticization is the human’s testimony: a comforting coping mechanism that beauty can be found in something as ugly as pain itself.

What is important to take away from this article is that everyone can and will, at some point, experience symptoms of various disorders. That does not mean you have it. Anxiety, mood instability, irritability, and sadness occur naturally every once in a while, especially when living in such a fast-paced environment as today’s world. But correlation isn’t always causation; until those habits interfere with your daily life, it’s not a disorder. Don’t listen to what social media creators have to say to you. It’s actually more than okay to be okay.

References

- Friedrich Nietzsche. “On the Genealogy of Morals“. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. California. 2012.

- Yuval Noah Harari. “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind“. Harper. New York. 2015.

- Facebook Manipulates Our Moods For Science And Commerce: A Roundup. NPR. Available here