By Elena Basati,

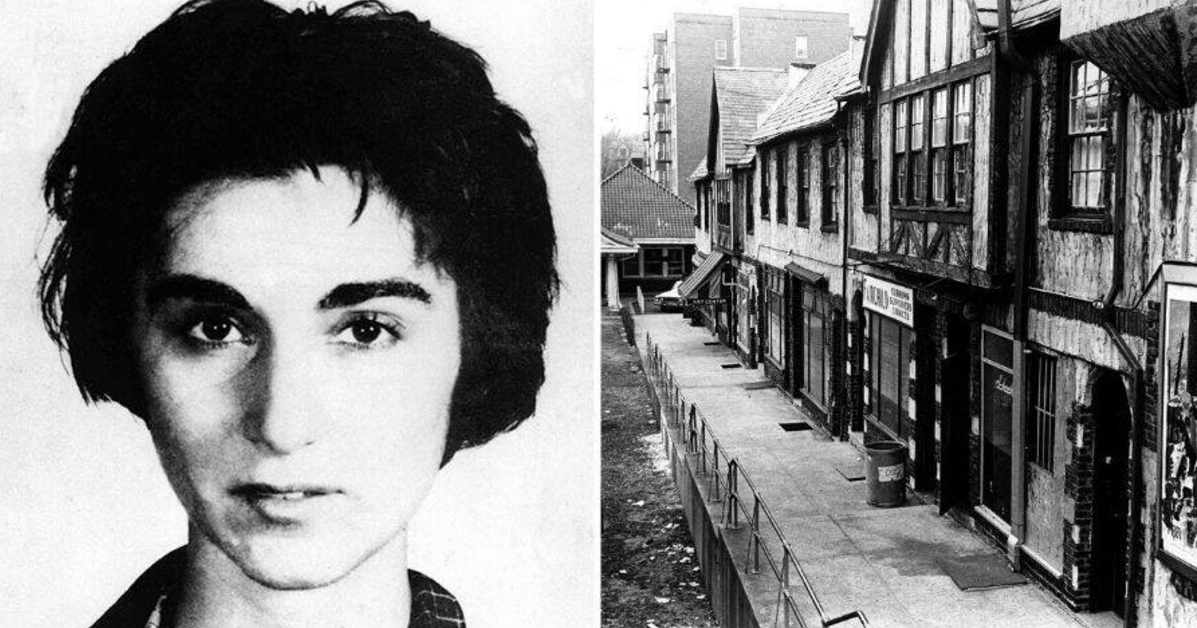

Late one night, Kitty Genovese was returning as usual from her work to her home in New York City, but that night she was stabbed to death. While she was approaching her building, Winston Moseley went behind her back and killed her. Was she alone in the parking lot? Didn’t anyone listen to her screaming, “Oh my God, he stabbed me! Help me!”? Moseley, afraid of her yelling and having in mind the possibility that someone could hear her, escaped. Indeed, he was right, people did listen to her crying for help since lights went on in the apartment buildings nearby. At least two people saw the attack, but no one called the police or went down to help her. Moseley, noticing that no individual reacted, returned to the spot and stabbed her 10 more times. Now, numerous people witnessed the act, but still no one responded. Only a friend and neighbor of Kitty finally approached her and held her, while she was dying. At this moment, the police were summoned by a witness.

How could so many people remain actionless when a fellow individual screams for help while bleeding? To most of us, such an act is absurd and cruel. We’d probably doubt the good nature of the individuals surrounding Kitty. Most likely we’d imagine ourselves being there and helping her. If we were there, she would have been alive now. Or maybe not? How much can we rely on the kindness of strangers?

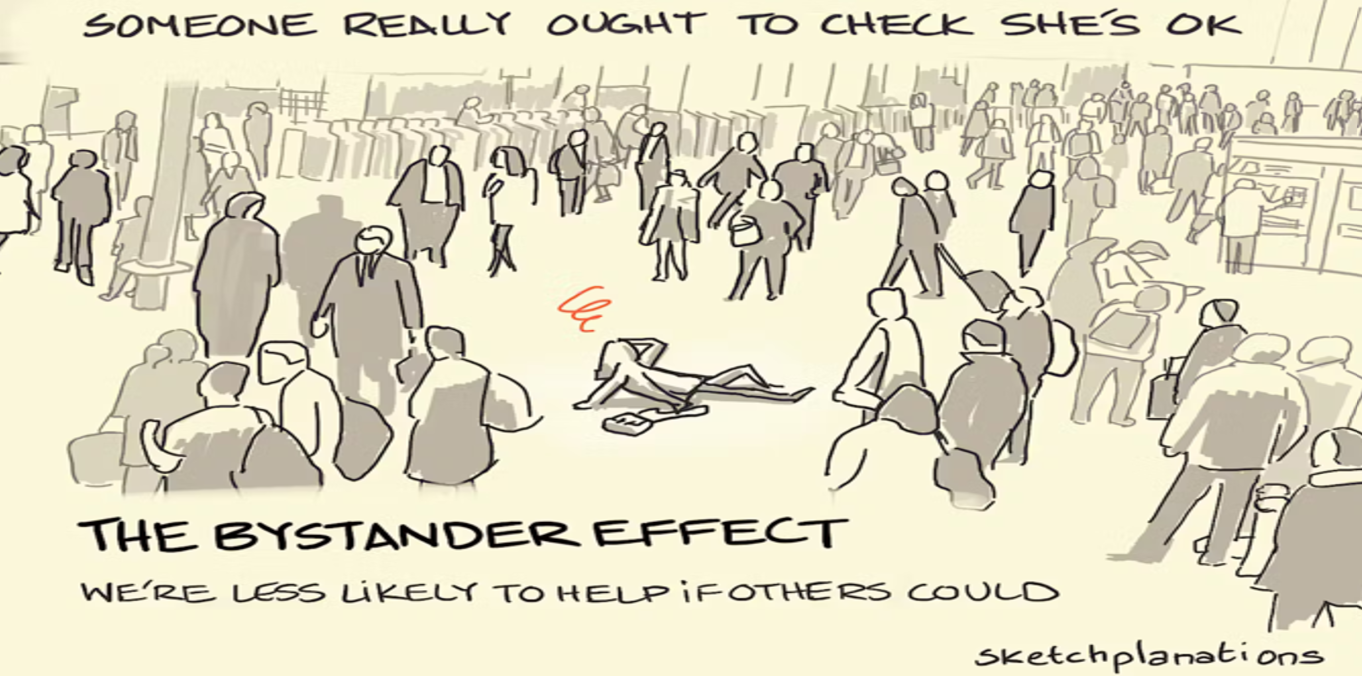

The Kitty Genovese case gained great popularity and it even became the reason the 911 phone call system was established. It also caused a huge stir in the scientific community and spurred a vast amount of research in social psychology. Attempting to explain the Kitty Genovese case, John Darley and Bibb Latané (1968) performed an experiment. They would play an audiotape of someone choking while speaking on the phone with the research participants. The researchers led one group of participants to believe that they were the only ones to witness the event and the other group thought that many people could hear them. Of the participants who thought they were hearing someone choking, 85% tried to help. However, of those who thought many people could listen to them choking, only 62% tried to help. The researchers came to the conclusion that the greater the number who witness an emergency the less likely any one of them will help. Darley and Latané named this phenomenon the bystander effect.

One explanation of the phenomenon involves diffusions of responsibility; that is when many people are around to witness an emergency, the individual’s perceived responsibility decreases. Imagine you are the only one to witness an emergency, you realize that you are also the only one that could help. However, if several people are around, you may not consider it your responsibility to provide aid. You’d most likely think that someone else can do it instead. This mindset probably was the reason Kitty Genovese died because people assumed that “somebody else must have called the police”.

The diffusion of responsibility isn’t the only possible explanation of the bystander effect. Other factors in addition influence whether or not people will take action to save another individual. Darley and Batson noticed that when someone is in a hurry, they are less likely to notice an emergency. Moreover, when many people are present doing nothing, one will look for social clues in others, this is an example of informational social influence. If they notice that no one provides any help they are more likely to act the same. Apart from the latter, the cost-benefit analysis claims that people will measure whether or not helping is worth the cost.

Altruism, in its simplest form, refers to actions taken to help others at a cost to oneself, often without any expectation of personal gain. From a purely evolutionary standpoint, this behavior appears puzzling. Richard Dawkins, in his book The Selfish Gene (1976), argues that altruism doesn’t make sense from an evolutionary perspective because natural selection favors behaviors that increase an individual’s survival and reproductive success, not the well-being of others. This creates a paradox: if evolution is supposed to promote selfish genes, why do humans — and even animals — often engage in selfless acts?

One explanation for this paradox is kin selection (Hamilton, 1964), which suggests that individuals are more likely to engage in altruistic behaviors when it benefits their genetic relatives. By helping kin, an individual indirectly ensures the survival of shared genes, even if it comes at a personal cost. For example, studies of macaque monkeys have shown that a dominant macaque will often share food with subordinates (Kay, Lehmann & Keller, 2019). This behavior might seem altruistic, but it may be driven by the fact that these subordinate monkeys are kin or group members who contribute to the overall success of the community. In this way, what appears as altruism might still serve an evolutionary function.

Ultimately, the psychology behind the bystander effect and altruism challenges our assumptions about human nature. While we like to think of ourselves as inherently helpful, the reality is that various psychological and social factors can hinder us from stepping up in moments of need. Even as altruism seems to defy evolutionary logic, concepts like kin selection and reciprocal altruism suggest deeper, often unconscious motivations behind our actions. But when faced with the choice to help or stand by, the question remains: will we rise to the occasion, or will we let others take responsibility?

References

- Dawkins, R. (1976). “The selfish gene”. Oxford University Press.

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). “Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. V 8 n(4), 377-383.

- Feist, G. J., & Rosenberg, E. L. (2021). “Psychology: Perspectives and connections (5th ed.)”. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Kay, T., Lehmann, L., & Keller, L. (2019). “Kin selection and altruism”. Nature Human Behaviour. V 3 n(4), 284-291.