By Katerina Taxiaropoulou,

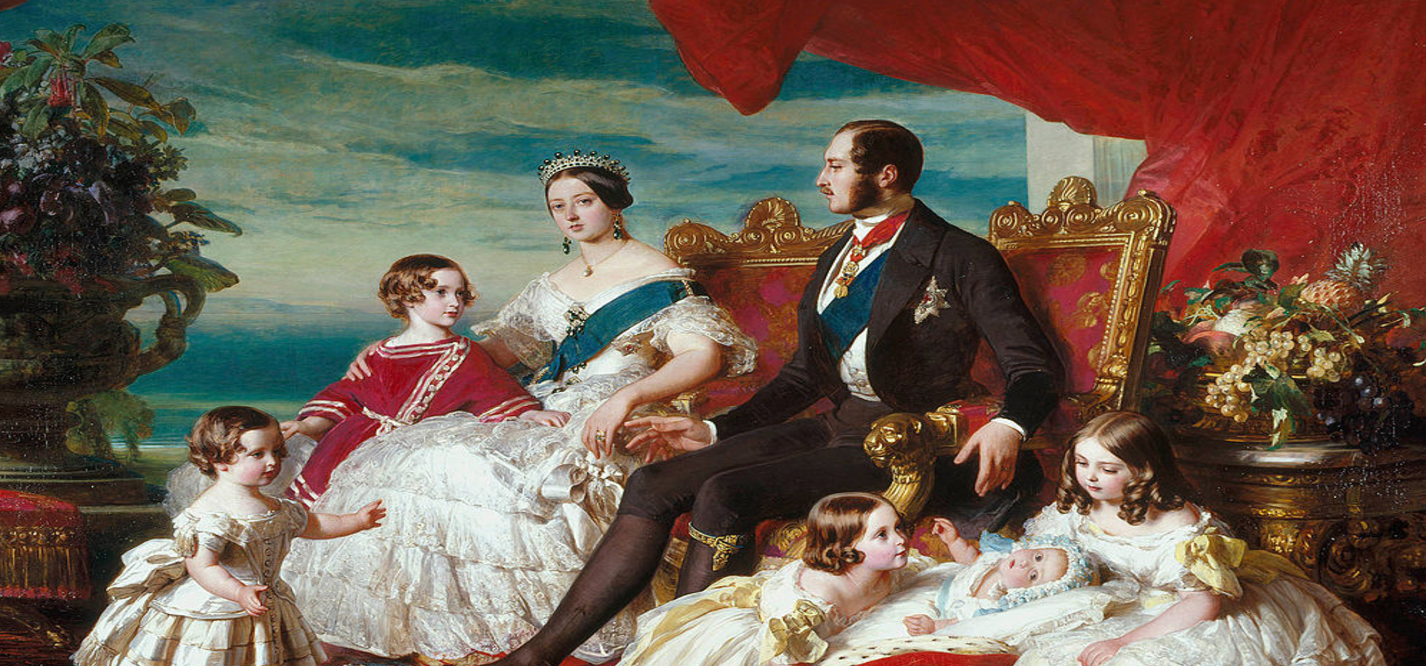

During the Victorian years, women’s place in society was a rigid one. With the emergence of the notion of the “separate spheres”, the woman was kept more than ever away from the public sphere and her domestication as a wife and a mother, in contrast with her husband’s occupation outside the house, was perceived as the natural course of things. And how could it not be so, when the ruler of the nation after whom the era was named was the absolute representative of true femininity: “centered on the family, motherhood and respectability”, “the mother of the nation”, Queen Victoria was a role model for every woman of the time (Abrams, 2014).

Concerning domesticity, everywhere, in domestic novels, in advertisements and newspapers, the idea that women’s place was in the private sphere of home and hearth was underlined. The ideal woman of that time was supposed to be entirely devoted to her husband and her God, accepting in this way her place in sexual hierarchy. She had to be pious, respectable and busy. She would achieve all these by devoting her life to the service of other people. The fulfillment of this cause was not regarded too much of a burden on women’s shoulders, since, according to the evangelical belief, the true woman was by birth innately good and morally superior.

For her husband, she was expected to take care of the house in such a way as to create “a haven from the busy and chaotic public world of politics and business” (Abrams, 2014). To achieve this she would have to undertake strenuous work. “It is a fallacy that most middle-class women were able to afford sufficient servants to allow them to spend their lives in idle leisure”, remarks the historian and professor at the University of Glasgow, Lynn Abrams (2014). In fact, most of these women could not afford more than one servant. They had to perform harsh physical labor, completing tasks like fetching and boiling water, washing and ironing clothes, scrubbing the floors with sand, even repairing underclothes, since most middle-class houses did not have flushing toilets.

Apart from managing the household however, women had one more very important cause to fulfill: motherhood. Motherhood in the Victorian times exceeded its association with just reproduction and acquired a symbolic meaning. In other words, motherhood came to mean more than just giving birth in that it was regarded as “the zenith of a woman’s emotional and spiritual fulfilment” (Abrams, 2014). The ideal Victorian woman would spend most of her time with her children, breast-feeding them, playing with them and educating them. And of course this reaction to motherhood was what deemed a woman, a true woman; motherhood was then the affirmation of her identity. On the contrary, childless, single women were considered “abnormal”, “inadequate” or “a failure” to their families, creatures “to be pitied” (Abrams, 2014). Childless women were also encouraged to take up a job as governesses or nursery maids to compensate for the loss.

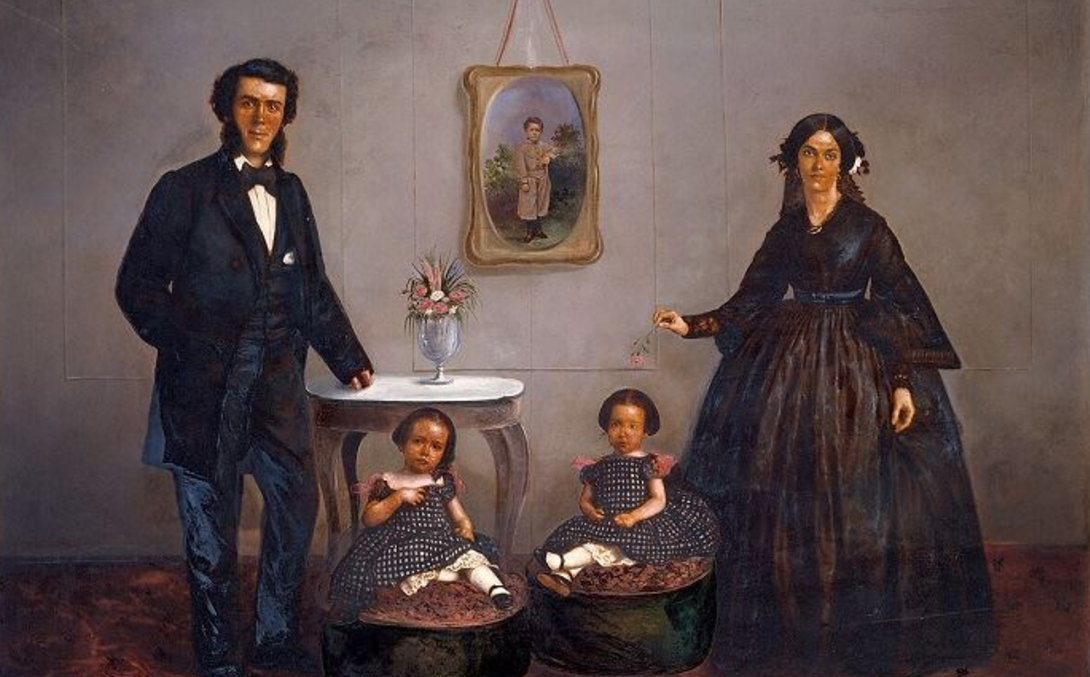

Motherhood however was also a full-time job, and a job bounded with much responsibility. Becoming a mother meant taking up a great “social responsibility” and “a duty to the state” (Abrams, 2014). Given this, becoming a mother put much more pressure on women of the working class, many of whom had to combine their duties as mothers with paid work. Yet, even for more privileged women, the psychological pressure coming with motherhood was no less. Indeed, according to Abrams, “responsibility for the appalling death rate amongst infants was roundly placed on the shoulders of mothers” (20014). A virtuous mother had to be present for her child 24 hours a day. Had she gone out in the labor market she would have been characterized as “irresponsible” and “neglectful”, a fact that inevitably led most women to a commitment to domesticity (Abrams, 2014). With that being said, the argument of this essay has reached full circle.

All in all, it seems that the Victorian ideas of gender were indeed patriarchal, restrictive and illiberal, leaving women with the very narrow space of a house to work on their personalities and evolve. Yet it should be mentioned at that point that many women during this era left in a way their homes to engage in philanthropist activities, mainly in poor people’s homes. Even though this occupation did not liberate women from the constraints Victorian society put on their sex, it provided women with “a little excitement, maybe even danger, and a means to self – discovery” (Abrams, 2014). It was this charitable activity that gave women a mission other than motherhood, and that inspired the formulation of many female associations. This philanthropic movement was where the first-wave feminists were born.

Reference

- Ideals of Womanhood in Victorian Britain. BBC- History. Available here