By Dimitra Gatzelaki,

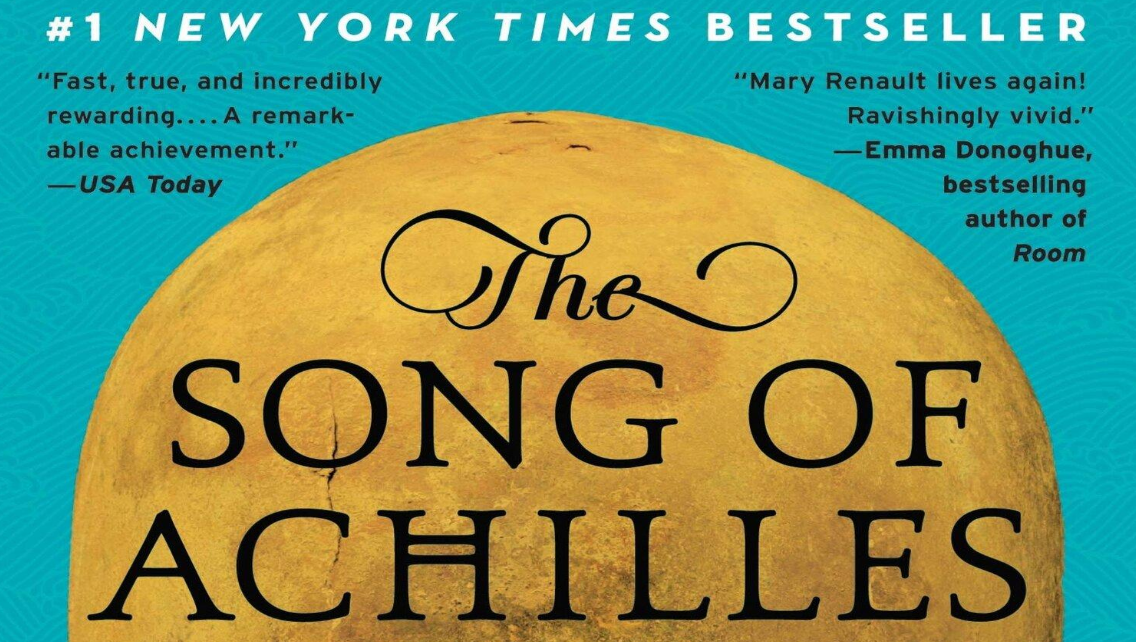

In 2011, Harper Collins publishes The Song of Achilles, a debut novel by an emerging author, Madeline Miller. Miller holds a BA and MA in Classics from Brown University, and had worked as a teacher and scholar until she made her literary debut.

As its title suggests, The Song of Achilles turns its gaze toward a figure both intimately familiar and well-sung in Greek myth, the warrior Achilles. Even though his place in Homer’s Iliad is central, his inner world, apart from his towering pride and wrath, is shrouded from the reader. In her novel, Miller grants Achilles a prominent voice and position —though not as the narrator. Rather, the storyteller is his cousin Patroclus. And this allows Miller to make of the narrative what she wants: a love story that reimagines, transforms, and is kindled by Greek myth.

“‘The Song of Achilles’ does not, in fact, belong to Achilles at all,” Daniel Mendelsohn writes in an article for The New York Times. And that rings true. It belongs to Patroclus, its narrator, as well as to Miller. In the Iliad he stands first and foremost a warrior, a hero forged in battle; in The Song of Achilles, Miller turns him into a lover. And although her novel doesn’t fit the traditional mold of an epic, it broadens the scope of the genre. Epics needn’t be limited to heroic deeds, spurred by love or pride; they can also encompass the complexities of love itself. Perhaps Miller wants to suggest that a love story, in its own right, can be as grand and worthy as any epic, and that the thrum of battle can, for once, be its background.

For the literary world, it looks like Miller did something right with her retelling of the Iliad, since The Song of Achilles was given the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2012. When I read it at 15 years old, after having been only briefly exposed to Homer’s epic at school, I was taken aback by Miller’s magnetic prose, of course, but also by her guts. Then, I told myself, it takes some courage to write about a homosexual romance between two epic figures etched in history, and to do it so beautifully. Now, I understand the implications of being a woman classicist (when, at the time of Miller’s studies in the early 2000s, the field was dominated by men) who chooses to transform a classic in such a controversial way so that, according to critics, “the result is a book that has the head of a young adult novel, the body of the ‘Iliad’ and the hindquarters of Barbara Cartland”. With how gatekept classics were (and still are), Miller’s thematic choice takes some guts indeed.

In her second novel, Circe, published in 2018, she continues with the theme of mythical transformations. This time she turns her attention to another of Homer’s epics, The Odyssey. Her inspiration for this novel is crystal clear; “the first time I read the Circe episode in the Odyssey, I hated it,” she writes in LitHub.

At 13, Miller was captivated by the endless trials of Odysseus, the lifelike portrayal of Gods, demigods, and monsters, the intrigue of Homer’s epic. In the episode with the witch Circe, where Odysseus got stranded in the wild island of Aeaea, she loved “the wolves and lions who draped themselves over Circe’s threshold … Odysseus’s buffoonish men being transformed to pigs by Circe’s drugged wine and magic”. As Odysseus confronted Circe, she anticipated a gripping duel, a true “battle of wits”; her fantasy was shattered at Circe’s swift, “feminine” submission at the sight of Odysseus sword (which is a phallic symbol). And so, the seed of her thirst to reshape Circe’s story was planted.

References

- Mythic Passions. The New York Times. Available here

- Restoring Power to the Women of Ancient Myth. LitHub. Available here