By Elena Basati,

Thomas Hobbes, in his work, Leviathan (1651), delves into the darker aspects of human nature, society, and governance. According to Hobbes, human beings are inherently selfish, cruel, craving for power and driven by desires that, in a state of nature, lead to chaos and anarchy. To escape this brutal existence, Hobbes argues that individuals must relinquish their freedoms to a powerful ruler —whom he famously calls the “Leviathan”— to establish order and prevent societal collapse. But Hobbes’ vision raises a critical question: What happens when obedience to authority becomes absolute?

To truly understand the effects of obedience, we must revisit one of the darkest periods in human history —World War II. During this time, the world witnessed how ordinary people could be driven to commit unimaginable atrocities under the influence of an authority figure. When Nazi soldiers were brought to trial after the war, many defended their actions by claiming they were simply “following orders.” The horrific events of the Holocaust forced society to grapple with unsettling questions: were all Nazis inherently evil, or can ordinary individuals be compelled to do terrible things when commanded by an authority figure? These questions lie at the heart of understanding the psychology of obedience.

Stanley Milgram was a Jewish-American psychologist, whose parents immigrated from Eastern Europe to the United States prior to World War II. However, like all Jewish families, his was deeply affected by the events of the war. With the support of his graduate advisor, Solomon Asch, Milgram decided to give an explanation of the Holocaust and investigate whether people could conform to orders even though the possibility of harming others is likely.

Milgram’s experiment was conducted at Yale University, using members of his community as participants. Upon arriving at the lab, each participant was seated next to another supposed participant, who was actually a confederate. They were then introduced to the experimenter, a professional in a white lab coat, who informed them that they would be participating in a study on the effects of mild punishment on memory. The roles of “learner” and “teacher” were assigned by drawing a note from a bowl, though the drawing was rigged so that the real participant always became the “teacher.”

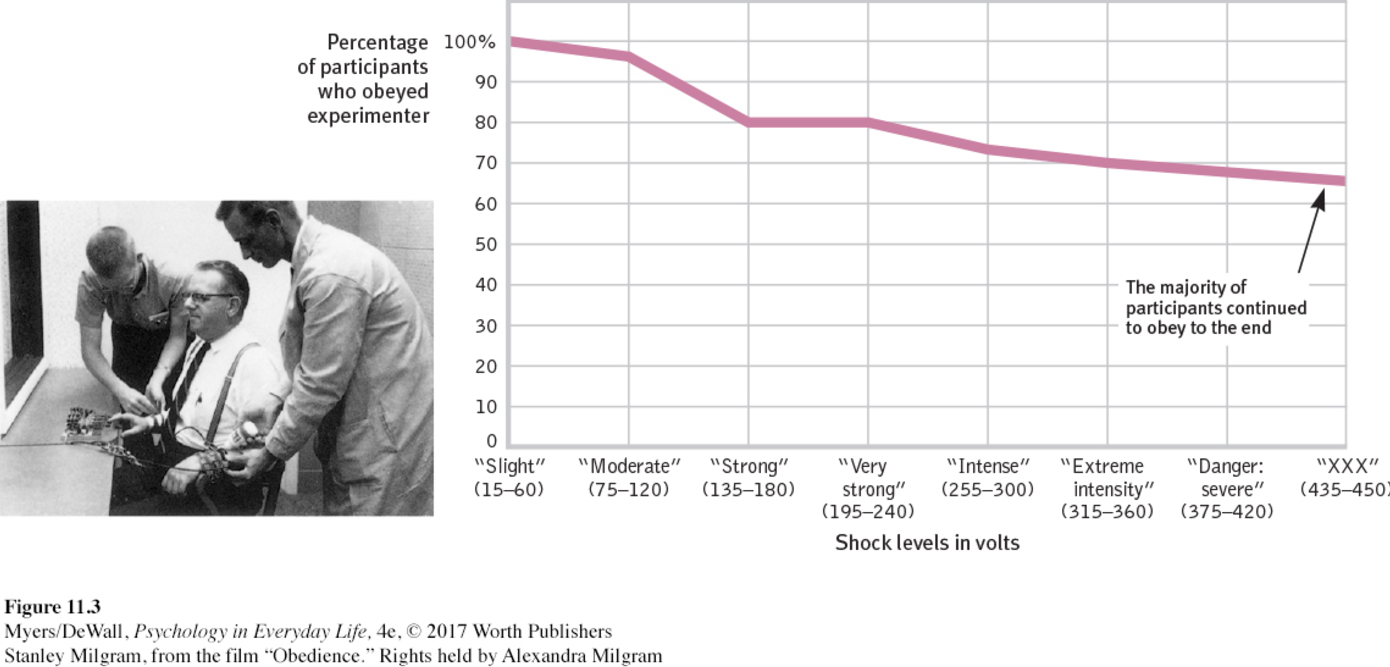

The “learner” (the confederate) was escorted to another room to begin memorizing and repeating lists of words. Each time the learner made a mistake, they would receive a mild shock from the teacher. The teacher, to simulate the learner’s experience, received a very low shock —this was the only real shock administered during the experiment. The teacher was then placed in a room with a table and a panel of switches labeled with voltage levels ranging from 15 volts (mild shock) to 450 volts (“XXX”).

As the learner began making mistakes, they received low-level shocks without much response. However, as the shocks increased in intensity, the learner reacted with yelps of pain. At this point, many teachers questioned the experimenter, who insisted, “The experiment requires that you go on”. Before the experiment, a group of psychiatrists predicted that only 30% of participants would administer shocks above 150 volts, less than 4% would reach 300 volts, and only 1 in 1,000 would go as far as 450 volts. Were the predictions accurate?

The actual results were far more shocking, leaving scientists astonished. At 150 volts, where the learner screamed, “Get me out of here! My heart is starting to bother me! I refuse to go on! Let me out!” obedience dropped from 100% to 83%. Despite their visible discomfort, most participants continued. Alarmingly, 65% of participants ultimately delivered the maximum shock of 450 volts, with both men and women equally likely to reach the highest level.

Milgram’s experiment shows that ordinary and reasonable people are able to do things that are cruel and cause great pain to others, in the presence of social influence. Even though many “teachers” protested when the experimenter urged them to continue, they simply obeyed. If asked “who is going to be responsible if that guy gets hurt?” the experimenter would reply “I have full responsibility”. Therefore, who is in the end responsible, the person that gives the order or the one that executes it? While Milgram’s findings do not fully explain the Holocaust, they offer valuable insights into the nature of obedience. They prompt us to ask: How far can an ordinary person be pushed to act against their moral judgment under authoritative pressure? What does this mean for our own capacity to resist unethical commands? How can we safeguard our personal ethics and responsibility in the face of powerful social influences? These questions challenge us to reflect on our own potential for obedience and the moral choices we face in everyday situations.

References

- Feist G. J. & Rosenberg E. L. “Psychology: Perspectives and connections” (5th.ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. New York. 2021.

- Hobbes T. “Leviathan”. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 1996.