By Vera Rodriguez,

The world witnessed the Vietnam War and the atrocities in Rwanda, and now it is not batting an eye at the illegal claim of Palestinian land by the Israeli government. The United Nations has repeatedly failed to act when atrocities were being committed, and even when it does say something, states seem not to listen. Given this situation, one could ask: what is International Criminal Law for? This article aims to reflect on that question through the Indonesian massacres, a silenced story that took years to be told.

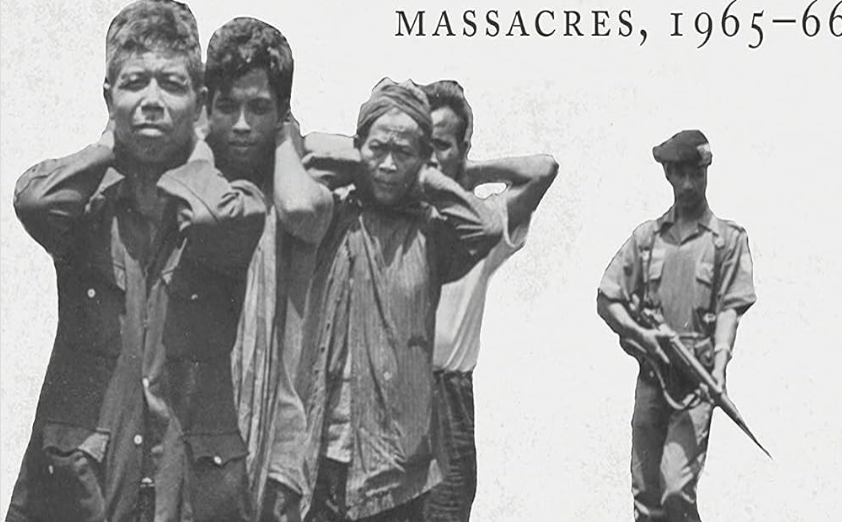

During the Cold War, Indonesia experienced a significant political upheaval in 1965 when a coup brought General Suharto to power. Under his regime, there was a brutal campaign against individuals associated with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). According to Geoffrey Robinson, one of the few scholars who has extensively studied this massacre, the killings were neither spontaneous nor random. They occurred systematically across various regions from the outset. The methods of execution were primitive, relying on basic tools such as knives and clubs, and the use of technology was limited to radios, guns, and motor vehicles. “In short, the vast majority of those killed were not targeted for anything they had actually done, and certainly not for any criminal act, but rather for their membership in lawful political and social organizations.”

The violence was brutal; estimates ranged from 78,000 killed to 3 million victims. Religious and ethnic tensions overlapped with political affiliation, which resulted in the targeting of lower-class and Chinese-descent Indonesians. The world saw it happening; however, there was not much conversation about it. Reports of the killings were studied with skepticism and sometimes even celebrated. The New York Times reported on the Indonesian situation under the headline “A Gleam of Light in Asia.” The US ambassador to Indonesia at the time explained the killings with the following statement: “The bloodbath visited on Indonesia can be largely attributed to the fact that communism, with its atheism and talk of class warfare, was abhorrent to the way of life of rural Indonesia, especially in Java and Bali.”. Lastly, recent reports revealed that the US was aware of the numbers. Despite this, they did not act in the UN to prevent the massacres from happening.

This absence of international action explains why Indonesia has no international ad-hoc tribunals such as Rwanda or Yugoslavia. The prosecution of international criminal justice is inherently political and closely linked to the post-World War II order. During the Cold War, many crimes went unjudged to avoid provoking tensions between the opposing superpowers. Furthermore, in the case of Indonesia, the persecution of individuals affiliated with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) aligned with the US’ broader geopolitical objectives of the time.

Today, the killings are hardly studied due to the inherent permissiveness of the acts by both the International Community and the regime itself. Suharto, Indonesia’s dictator at the time of the massacres, remained in power until the 90s. This led not only to the complete denial of broad Human Rights violations in the country but also to a scarred society. The perpetrators remained free of punishment and the victims did not receive closure due to the lack of national or international prosecution. Besides, political prisoners were unjustly retained for years. Nationally, the massacres remain a silenced tragedy. On the global sphere, this “killing season” remains yet another tragedy that the world was watching but failed to intervene when it was due.

In 2012, a film by Joshua Oppenheimer, “The Act of Killing,” gave light on the massacres and led to a Human Rights report that same year. A few months later, activists successfully initiated judicial procedures in an International Court in the Hague. Historians such as Geoffry Robinson and numerous NGOs also contribute to the reconciliation process, giving voice to the silenced. Despite these efforts, many of the victims are afraid to speak up about their experiences, fearing reprisals.

This article might convey a pessimistic message. However, it does not have to. If the Indonesian example teaches anything, it is that human rights violations without prosecution are not permissible. With time, activist groups took the Indonesian case to court. Although not as much has been achieved, it shows the impact and outreach a group of coordinated action can have. Similarly, as political and as convenient as the International Criminal Law judgments may be, there needs to be a critical analysis of the story and a fight for fair judgment and the end of violence.

Many of us criticize international law as inefficient, and understandably so. Why make International Law if it is not enforceable? An important reason is that the law reflects and contributes to a general socio-political tendency. Things might seem impossible until they happen, but announcing them, even in non-enforceable documents, makes them more achievable. Indeed, there are many criticisms to be made, yet falling into a narrative of complete pessimism is not the answer. Political activism, whether in academia, social circles, or institutional structures, cannot stop believing in a better world and pushing for a fairer future. Ultimately, I am writing about the Indonesian massacres thanks to activism and the refusal to let this story be forgotten. International Criminal Justice works sometimes, yet organized collective action must always be present.

References

- Robinson Geoffrey. “The killing season: A history of the Indonesian massacres, 1965-66”. Princeton University Press.

- Donnedieu de Vabres Henri. “The Nuremberg trial and the modern principles of international criminal law.”Oxford Academic

- Geoffrey Robinson Presents on the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66. USC Dornsife. Available here

- Indonesia, Documenting Violence in Indonesia. Yale University. Available here