By Elena Basati,

In Greek mythology, Death is personified as Thanatos, a masculine figure. However, in languages like French, Death takes on a feminine form (La Mort). Norse mythology presents a goddess of Death named Hel, while Roman mythology has Pluto, the god of the Underworld. The gender of Death varies across cultures, raising an intriguing question: Is Death female or male? While Death’s gender remains ambiguous, one thing is certain: it is primarily a woman’s domain. From ancient Greece to modern times, women have played crucial roles in death rituals and mourning. They prepared the deceased for burial, took an active part in the funeral, were hired as professional mourners, and continued grieving long after the ceremony. This article explores women’s participation in burial rituals and lamentation, how these practices challenged patriarchal ideals, the consequences of their suppression, and their influence on the perception of death. It also examines modern women’s attempts to revolutionize the death industry and foster a positive attitude towards the inevitable.

Women’s Historical Role in Death Rituals

The Greek tragedy “Antigone” by Sophocles centers on the dead body of the protagonist’s brother, Polynices. Deemed a traitor of Thebes, Polynices is denied a proper burial, unlike his sibling, Eteocles. Creon, their uncle and the king, declares that anyone defying his law will be punished. Despite this, Antigone buries Polynices and ultimately takes her own life while imprisoned.

From ancient Greece to the present, women have been central to death rituals and mourning. The Greek verb “κηδεύω”, meaning to bury, also signifies tending to a bride or corpse, highlighting the connection between death and femininity. Women were the primary caregivers of the deceased, ensuring they were well-prepared for the afterlife. In western Macedonia, professional mourners —mainly women— sang for the deceased, displaying rhythmic movements, beating their breasts, tearing their cheeks, and loosening their hair or scarves. These practices were not unique in Greece. In Ireland, women engaged in keening (Caoineadh), where in Gaelic it translates to “crying”. A ritual where they lamented and sang for the dead, ensuring the soul’s eternal peace. Keening women played a crucial role in preserving tradition and enriching culture.

Keening was more than an expression of grief; it actively challenged traditional gender roles. Judith Butler argues that gender is not innate, but a series of performed acts. In keening, women resisted stereotypes of passivity and silence, asserting their presence and agency in public. Lamentation was not only about caring for the deceased; it was an opportunity for women to be heard and respected in their communities. Keening women, perceived as embodying a “divine madness,” allowed individuals to express collective grief through their voices and bodies. The Lament for Art Ó Laoghaire, composed by his wife, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, in honor of her murdered husband, is widely regarded as one of the greatest poems of the 18th century. In a striking and symbolic gesture, she depicts herself drinking his blood from her palms.

The Roman Catholic Church, threatened by these practices, labeled them as witchcraft and advocated for “silent” wakes. In the 19th century, keening faced severe suppression, labeled as pagan and targeted by Christian and Victorian values. Lamentation wasn’t perceived only as a pagan ritual but a woman’s practice as well, and keeners were even whipped by priests, when they were seen in graveyards lamenting the dead. The decline of the Irish language further diminished keening.

The Shift to Medicalized Death

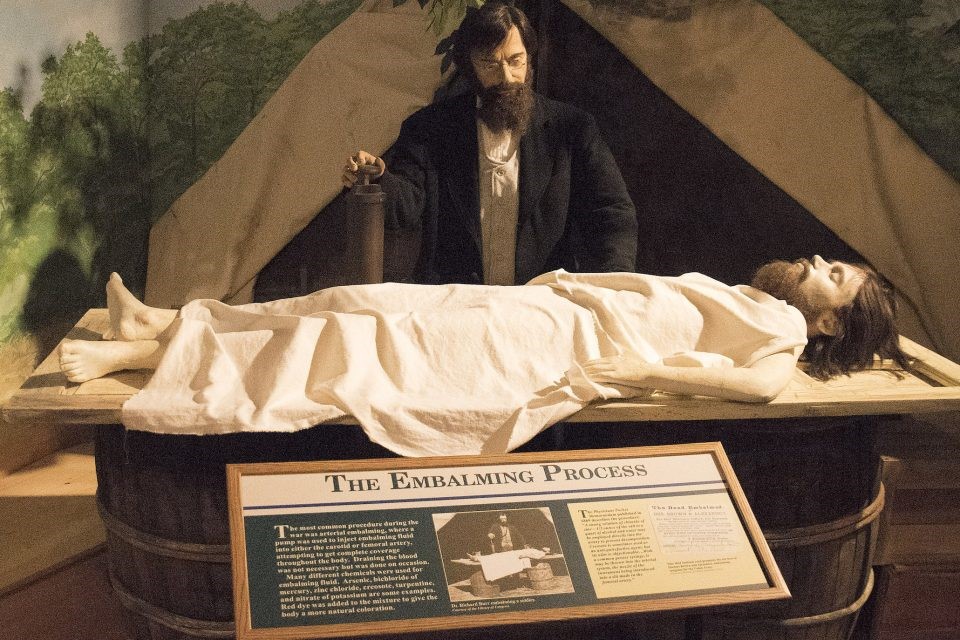

The 19th century American Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in American history, marked a significant shift in how the dead were treated. With thousands of soldiers dying, the practice of embalming emerged to preserve bodies for transportation. This shift from ritualistic to medicalized burials fundamentally changed our perception of death and the dead body.

The Modern Death Positive Movement

Today, most people die in hospitals rather than at home. Death is seen as a medical failure, and many have never seen a dead body. In contrast to the 1800s, when Parisians visited graveyards to observe unidentified bodies for entertainment. Over the past 150 years, death has become a male-dominated field with most doctors, embalmers, and morticians being men.

Recently, women have begun to reclaim their place in the death industry, suggesting alternative burial procedures and enrolling in mortician classes. The percentage of female mortician students has risen to approximately 57%. The “Death positivity” movement aims to remove the stigma from death, encouraging acceptance and a more humane approach. By openly discussing what happens to our bodies after death and who takes care of them, women are reclaiming their role in the industry.

Caitlin Doughty, a leading figure of the “Death positivity” movement, challenges the “culture of death denial” in her book “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes“. She embraces the temporality of our bodies and advocates for ecological burial practices that protect the environment. Doughty argues that a “good death” involves accepting the inevitable. This movement, reminiscent of the keeners, promotes a less medicalized view of death, encouraging a return to more natural and traditional practices.

Exploring women’s roles in burial rituals and mourning reveals the intersection of gender roles, tradition, and the perception of death throughout history. Acknowledging this past sheds light on women’s significant contributions to culture and tradition despite centuries of suppression. Samuel Beckett’s phrase, “Women give birth astride of a grave”, reflects the duality of life and death that women embody. The Death positivity movement opposes the notion that death must remain concealed, redefining death in a holistic and less sterile manner. By doing so, women are challenging long-standing anthropocentric views and proposing a more inclusive and natural approach to death.

References

- Margaret Alexiou. “The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition“. Rowman & Littlefield. Maryland. 2002.

- Bourke, A. (1988). “The Irish lament and the grieving process”. Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15(1-3), 187-200.

- Butler, J.. “Antigone’s claim: Kinship between life and death“. Columbia University Press. USA. 2000.

- Danaher, K.. “Ireland: Folklore and tradition“. Mercier Press. Cork. 1981.

- Doughty, C.. “Smoke gets in your eyes: And other lessons from the crematory“. W.W. Norton & Company. New York. 2014.

- Guthke, K. S.. “The gender of death: A cultural history in art and literature“. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1999.

- Macintosh, F.. “Dying acts: Death in ancient Greek and modern Irish tragic drama“. Cork University Press. Cork. 1994.

- Ó Tuama, S., & Kinsella, T. (Trans.). “The lament for Art O’Leary“. Dolmen Press. Dublin. 1981.