By Dimitra Gatzelaki,

We are now traversing the first month of summer – and, like every summer, the reading mood changes. Every year around this time I find myself being drawn to the warm, transcendental feel of Japanese novels, their cruel winters and crueler summers, their idiosyncratic characters. Often small in length, contemporary Japanese novels have nevertheless much to say: about one’s elusive identity, their place in an orderless society, the meaning of life. When I’m in a mood to think deeply, they make for an exciting summer.

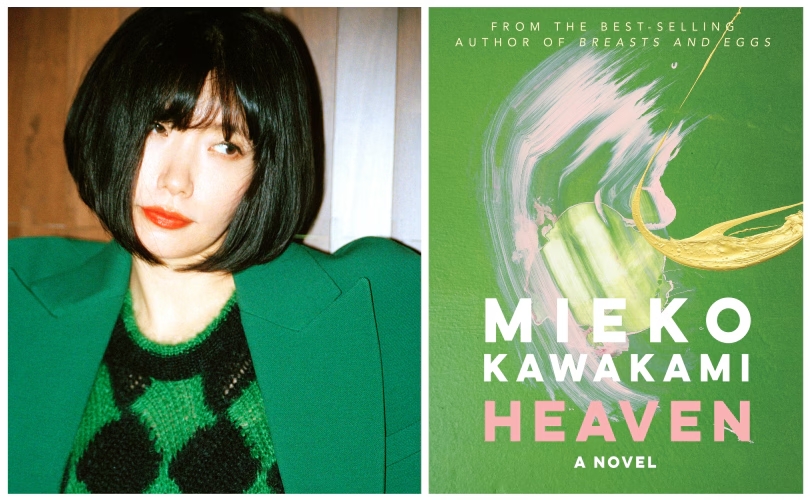

Heaven is Mieko Kawakami’s first full-length novel, published in Japan in 2009 and brought into the Western world in 2021 by the translators Sam Bett and David Boyd. The feel of reading Kawakami’s novel can be well encapsulated into one of its quotes: “the July sky was saturated with summer. Nothing moved over our heads.” The tight, stifling feel the novel induces comes as a combination of Kawakami’s writing style and the subject matter, which is bullying. Heaven deals with a 14-year-old boy who remains unnamed, and whose defining trait is his lazy eye, which subjects him to brutal bullying from his classmates. And so, his name, his only identifier, a nickname given by his bullies, contains the very thing he wishes to escape: “Eyes”.

And so, the novel’s title assumes an air of irony. The torments the narrator has to suffer without objection, from being stuffed into a locker to having his head kicked around like a soccer ball, are anything but heaven-like. Yet, perhaps in Kawakami’s novel, heaven isn’t a place or a state of living, but another person or an ideal. For Eyes, heaven becomes embodied in someone else: his classmate, Kojima, who is also bullied by the girls in their class. The two develop a strong relationship blooming from a shared bond, that of terror and suffering. During summer vacation, Kojima takes the narrator to the art museum to show him her favorite painting, “Heaven”. They don’t end up seeing it, but as they sit outside under the sun, Heaven for the narrator becomes contained in that very moment, and he reminisces about it throughout the narrative.

What draws the narrator closer to Kojima is that searching in her “lucid eyes” and dark face, he doesn’t see revulsion or cruelty, but kindness and understanding, even intrigue. “I really like your eyes”, she tells him, and he replies, “No one’s ever told me that before. Ever”. It’s like Kojima sees right into his core: “You’ve gone through so much because of your eyes. It’s a painful thing, I know, but it’s also made you who you are. … Because we’re always in pain, we know exactly what it means to hurt somebody else”. Her philosophy on what they’re both going through is that it has some meaning, that everything has meaning. Suffering, too, can lead to transformation. Her belief system is fleshed out through various striking monologues, one of which is found in one of her letters to Eyes:

“I felt sorry for them when they laughed in my face and called me names or came after me in the bathroom. But if I told them everything I’m telling you, they would never understand. … They need to learn about themselves from what they’ve done to me. That would be enough to justify my life.”

Yet what makes Heaven so riveting is that we get to hear the other side as well, that of the bullies. In the spur of the moment, entirely disoriented and on the verge of depression (“I started crying all night long. … Too many times to count, I sat paralyzed in bed and watched the night come to an end”), the narrator confronts one of his bullies, Momose, who he meets by chance at a relatively “safe” environment outside school, the hospital. Startling the reader with his newfound courage, which stems from somewhere unknown even to himself, he asks Momose why he and the others torment him. And the answer, raw and honest, startles the reader even more; “Nobody does anything because they have the right. They do it because they want to.”

A lengthy debate follows between them, one where Momose lays his own worldview bare. And it is the polar opposite of Kojima’s: he thinks that cruelty and bullying have no meaning at all. “None of this has any meaning,” he tells the narrator. “Everyone just does what they want. They have these urges, so they try to satisfy them. Nothing’s good or bad.” Intrinsically nihilistic, this view counters everything Eyes believes in, everything he’s been told by Kojima. But he can’t contradict it. To me, it seems just as valid. For the victim, suffering is bearable only if it has meaning; for the victimizer, inflicting pain is bearable only if it has none. Ultimately, Momose ends his part with the statement that “some people in this world can do things, others can’t”, and so brings the narrator face-to-face with his own helplessness.

Trapped in the center of what Kojima and Momose each represent, the narrator doesn’t know what’s right. At the end of the novel, after Kojima has severed ties with him for considering to get rid of his lazy eye through surgery (“But your eyes were a gift. Now you want to throw that away, the thing that brings us together?” she told him), he takes this thought and turns it into action. Is this a sign that he agrees with Momose, that he adheres to his bully’s convictions? Or is it simply a way to prove to himself that he can escape this loop of suffering by actually doing things? There is no answer.

Nevertheless, Kawakami’s prose in the last scene of Heaven is mesmerizing; she narrates the moment the protagonist first sees the world in its full-fledged, rich depth. “Everything was beautiful”, he keeps repeating. Rid of his defining trait, his lazy eye, the mystery of who he is turns full circle. Kawakami’s description gives the sensation that he’s reborn through tears, through light. And perhaps the end of one painful story is the beginning of another; one filled with hope and promise.

All in all, Heaven, although short, makes up for its length in depth and meaning. If you come across the book at a library or local bookstore, I’d definitely recommend giving it a go.

References

- Heaven. Harvard Review Online. Available here

- Mieko Kawakami. “Heaven”. Picador. UK. 2021.