By Vera Rodríguez,

Names are political and their use entails power. Although it is a seemingly trivial endeavor, describing a region is, at its core, a conscious and highly strategic choice. Trump was extremely aware of this when he chose to boost the term “Indo-Pacific” when referring to Asia. Before, it had always been “Asia” or “Asia-Pacific”. The shift to the Indo-Pacific was understood as a geostrategic construct to contain China. After a while, a few European states followed the trend, namely France, the Netherlands, and Germany. Finally, in 2021, the European Union published its first Indo-Pacific strategy. Why this shift? In short, the West has become increasingly worried about its overreliance on China, as it is a non-democratic state with a huge bargaining economic power. This article aims to give a comprehensive and brief guide to understanding the Indo-Pacific, its importance, and its complexities.

Although tensions with China had been latent since the early 2010s, a shift occurred after the COVID-19 pandemic. The realization that many essential products were being produced outside of the EU, and even the continent itself, made Brussels consider its overreliance on China. Besides, Beijing has had many other “red flags” that would make it an unreliable and untrustworthy partner, such as spying scandals in some European states or human rights abuses in the Xinjiang province. Furthermore, the security alarm is also a matter of worry. The Chinese navy is growing at a fast pace, and this is putting pressure on the already contested South China Sea. None of these issues were new, but a combination of Trump’s increasing antagonization of the country and the EU’s overreliance on an increasingly powerful state were the ultimate “red flags” for Brussels.

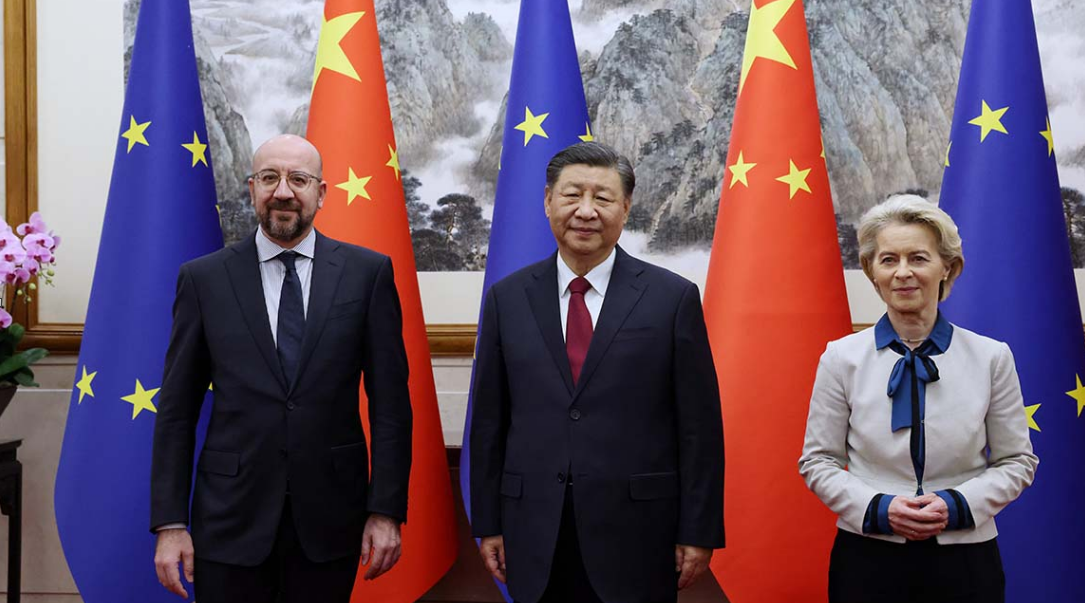

Since then, the EU has coined different terms to distance itself from Beijing. The clearest one is the replacement of Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific. However, the EU’s use of “competitor and systemic rival” or Ursula von der Leyen’s “de-risking” terms have not been well received by the Asian power. In contrast, this narrative remains at odds with the EU’s economic activities. In 2023, China remained the EU’s largest partner for good imports and third for exports. Considering this data and background, can the EU see beyond China? This question could be explored from many angles. This article will tackle it providing an overview of the countries that Brussels is talking to when it is aiming to engage less with Beijing.

In terms of Northeast Asia, the EU is looking at Japan and South Korea. These are the so-called “like-minded” countries. Therefore, cooperation does not only appeal to the economy but also to the EU’s favorite topic: values. Following this idea, Brussels has pushed personal data protection standards with both partners, as well as comprehensive economic agreements that make them also aligned in interests (i.e., digital partnerships). With the idea of re-arranging its source of semiconductors, which would otherwise be Taiwan, the EU has signed deals with Japan. The cooperation with these countries is straightforward, as they are allied with key Western powers such as the EU or the US.

In Southeast Asia, things are more complicated. The most important and interesting player is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). They are an international organization born during the Cold War, that throughout the years became more economically integrated. This group eventually grew to the current number of 10 members. This alliance is today’s most promising Southeast Asian economy. Many key regional players such as Japan, South Korea and China have engaged with them and formed “ASEAN+3”. The EU has also signed agreements and initiated cooperation with this alliance. They provide agricultural exports, raw materials, such as nickel from Indonesia, petroleum and coal from Malaysia and Brunei, and the list goes on. In short, a collaboration with them would be perfect to avoid overreliance on China.

Nevertheless, ASEAN countries are also involved with China. They participate in economic programs, the most important being the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This is Beijing’s most extensive strategy to gain influence in the world, not only in the region. Trading influence with money is something many international actors have done and continue to do to this day. However, this complicates things for the countries themselves, as China is also engaging in territorial disputes, performing naval exercises in their shared sea. This mixture of economic dependence and an increasingly tense security situation is not a good prospect for these countries. Lastly, ASEAN countries are not homogeneous in their political stances, some are more leaning toward China (Myanmar, Cambodia), while others confront it (Vietnam, Indonesia). This divides ASEAN’s joint political capacity.

Although a lot more could be said, the main takeaway from this article is that the EU needs to engage with the Indo-Pacific. In doing so, its challenges are many, although could be grouped into the following three. First, the structural design of the EU. The European Union lacks a strong security foreign policy, and some of the main worries of these countries, especially in Southeast Asia, are closely tied to this matter. Second, the war in Ukraine has understandably shifted the EU’s attention to its immediate borders. Third, the engagement of the US could make the EU’s interests in the region be seen as an “anti-China” coalition. If the EU wants to be strategically independent, it needs to be independent also, to a certain degree, from the US. This is not the case yet in the Indo-Pacific.

References

- Minghao Zhao. “Is a New Cold War Inevitable? Chinese Perspectives on US–China Strategic Competition,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics V 12 n(3)

- Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge. U.S. Department of Defense. Available here

- National Security Strategy of the United States of America. USNI news. Available here

- Sutter, Robert G. Chinese foreign relations: Power and policy of an emerging global force. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Reimagining EU-ASEAN Relations: Challenges and Opportunities. Carnegie Europe. Available here

- EU-China relations: De-risking or de-coupling − the future of the EU strategy towards China. European Parliament. Available here