By Elena Bassati,

The revolutionary feminist masterpiece, The Yellow Wallpaper, written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman and published in 1892, delves into the female psyche while critiquing societal norms and oppressive patriarchal structures. The story revolves around a young unnamed woman suffering from what appears to be postpartum depression, labeled as “temporary nervous depression”, and her physician husband’s futile attempts to treat her. In her private journal, the protagonist documents their retreat to a summer mansion, suggested by her husband John, who believes it will aid her recovery. This story exemplifies patriarchal medical practices, the stigmatization of mental illnesses, cases of misdiagnosis, and ineffective treatments proposed by male physicians.

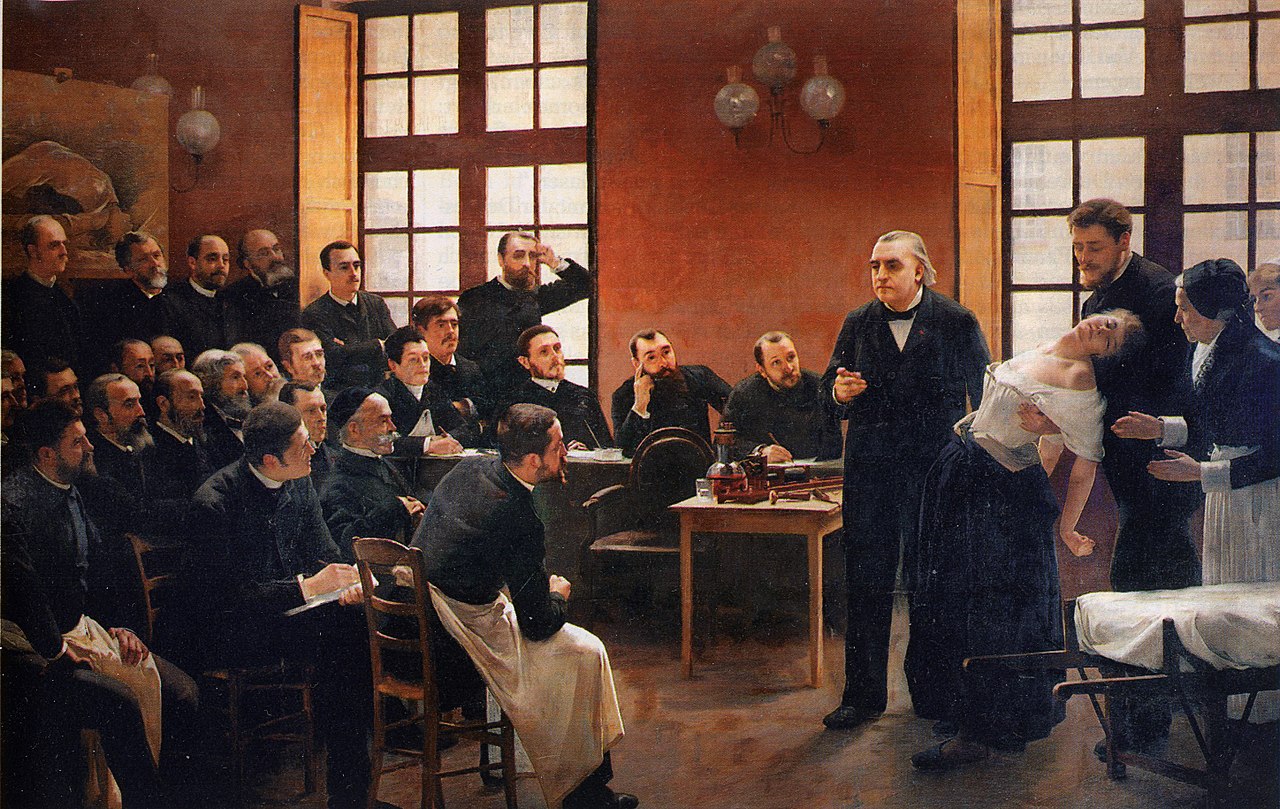

Understanding the medical landscape of the late 19th century, particularly in neurology and psychiatry, is crucial. In 1885, Jean-Martin Charcot, hailed as the “world’s greatest neurologist”, was renowned for his lectures on hysteria. Sigmund Freud attended these lectures and subsequently published his paper On Male Hysteria to the Vienna Society of Physicians in October 1886. Freud’s study elicited widespread reactions, with critics sarcastically questioning whether he knew the etymology of the word “hysteria”, derived from the Greek “hysteron”, meaning uterus. Until the late 19th century, the medical consensus held that only women could suffer from hysteria, due to the erroneous belief that they were more prone to mental illnesses. This notion traces back to Ancient Greece, where Plato in Timaeus suggested that hysteria was female madness attributed to a lack of normal sexual life. Hippocrates supported this view, naming the condition “hysteria”.

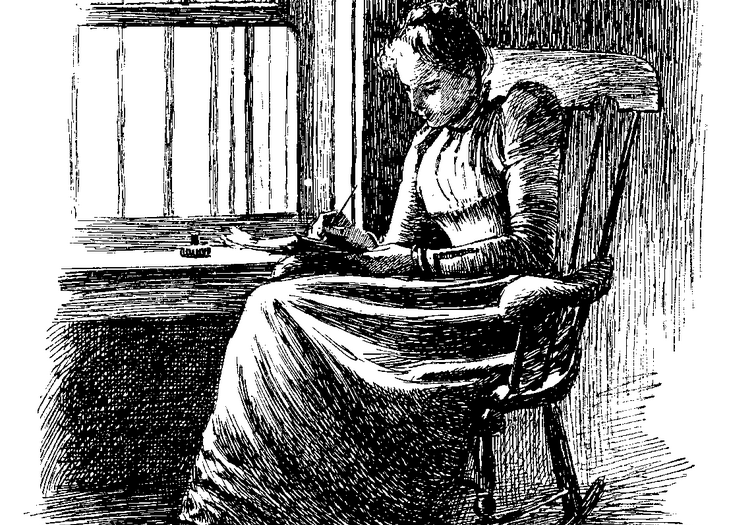

In The Yellow Wallpaper, society has made little progress from the era of Plato and Hippocrates, as medicine still relies on stereotypes and patriarchal ideas. A common treatment for hysteria at the time was the “rest cure”, promoted by American physician Silas Weir Mitchell, who advised women to avoid any mental or physical activity. Charlotte Perkins Gilman was prescribed this treatment when she consulted Mitchell for her nervous breakdowns and melancholic tendencies. In her essay Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper, Gilman describes her personal experience with Mitchell, who claimed that nothing severe was wrong and advised her to stop writing and simply rest. After three months of following his orders, Gilman found her condition worsening, prompting her to resume her work. With a friend’s help, she left her husband, moved to the States, and became a writer.

In The Yellow Wallpaper, Gilman draws from her personal experience, using the narrator to highlight the daily struggles women faced due to patriarchal silencing. The new mother is unable to fulfill the duties imposed on her by 19th-century society. Consequently, her “concerned” husband confines her to a mansion and forbids her from engaging in any satisfying activities. This irrational solution introduces two other female characters molded by patriarchy, unlike the deviant protagonist. Mary, symbolizing the Virgin Mary, is “so good with the baby”, and Jennie, whose name means female donkey, is “a perfect and enthusiastic housekeeper” with no aspirations beyond caretaking. These characters exemplify the limited roles of women in reproduction and caretaking. Meanwhile, John epitomizes male discourse, being controlling and dismissive of his wife’s health complaints, ultimately entrapping her in a room that exacerbates her condition.

Confined in the room with the yellow wallpaper, the protagonist’s mental health deteriorates. The wallpaper’s color isn’t coincidental, as yellow was associated with decay and illness in the 19th century and it symbolizes her worsening state. She becomes obsessed with the wallpaper, believing a woman is trapped inside it, an allegory for the actual feelings of women experiencing patriarchal oppression and confinement. At the story’s climax, she tears down the wallpaper to “free the woman”.

This short story is a powerful protest against a male-dominated society that silences, restricts, and abuses women. Despite its brevity, the word “but” appears 56 times, illustrating how the narrator’s speech is continuously interrupted and contradicted. She begins her sentences with “personally” (“personally I think that congenial work… would do me good”) to distance her opinions from her husband’s. In “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf addresses the increase in “insanity cases” in the 18th and 19th centuries, attributing it to women being confined indoors for millions of years, leading to depression. How many years must pass before women’s voices are heard and their ideas are not doubted and contradicted? How many wallpapers must be torn down before no woman is left captive?

References

- David Hothersall and Benjamin J. Lovett. History of Psychology. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 2022.

- Mark J. Adair. “Plato’s View of the Wandering Uterus”. The Classical Journal. Vol. 91, No. 2. pp. 153-163.

- Karen Ford. “The Yellow Wallpaper and Women’s Discourse”. Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature. Vol. 4, No. 2. pp. 309-314.

- Mikaella Demetriou. The Framing of Female ‘Disease’ in The Yellow Wallpaper and Jane Eyre. University of Reading, BA in English Language and Literature. Available here

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Why I Wrote The Yellow Wallpaper. The American Yawp Reader. Available here