By Dimitris Kouvaras,

A prestigious political position opens up after an unexpected death. An outsider is thrust onto the vacancy without direct public approval by a “political machine” controlled by an industry tycoon, only to be controlled himself as a docile frontman. Upon entry to the high echelons of power, the newcomer is disillusioned to discover a world of corruption, where esteemed statesmen are proved to be nothing but irresolute pions. What from without seemed as an institution serving democracy, from within seems a pretentious farce.

You might have guessed that the above is a description from a film, and in that case you are correct. However, these (imaginary) circumstances don’t concern a fictional dystopia, but one of the most celebrated institutions of the United States: the Senate. Surprisingly, if one considers the institution’s history and procedure, Frank Capra’s satire in “Mr. Smith goes to Washington” appears not so distant from reality. For, although the U.S. government is supposed to be “of the people, by the people, for the people”, as Lincoln proclaimed victorious in his Gettysburg Address, its persistent flaws, exclusions and procedural hindrances render such a claim euphemistic at least. The Senate, in parts of its tumultuous history, is a prime example of how politics can go rogue against public sovereignty and democratic principles when so vast and heterogeneous a state has to be run amidst geographical and ideological splits.

Speaking of splits, let’s turn to the Senate’s history first. Its origin lay in a compromise for a bicameral Congress reached in the Philadelphia Convention. In the 1780s the U.S. was no more than a nascent conglomerate of 13 states corresponding to the British American colonies, held together by the Articles of Confederation. Under this scheme, and due to the ideological correlation of centralised government with London’s oppression, states’ interests prevailed in the first Congress, which consisted of one representative for each. Small ones, like New Jersey, were favoured by equal representation and pressed for it to continue undue the new Constitution. The result was no other than the Senate. Combined with James Madison’s Virginia plan for proportional representation, embedded in the House of Representatives, it formed Congress as we know it. Yet, the Senate had the upper hand.

As a less populated body, the Senate was framed to be a highly deliberative institution involved in contemplating complex policies, thus entrusted with enlarged debate margins. The six-year terms of senators were intended to bolster stability, opposite to the House’s fluctuations. Besides, it was granted the privilege of approving the numerous civil office appointments made by the President. However, the downside was that from the very start it was an elitist institution. Until 1913, its members were elected by state legislatures rather than popular vote, while still in many states the governor can appoint new senators if unexpected vacancies occur, just like in Capra’s film. No public consultation. No fair representation either, as all states get two senators. California’s almost 40 million citizens count the same as Wyoming’s mere 600,000. Of course, the historical federal structure of the U.S. explains this discrepancy, yet at the framer’s time population differences were considerably slimmer and states non-partisan. The framers likely didn’t expect parties to develop at all.

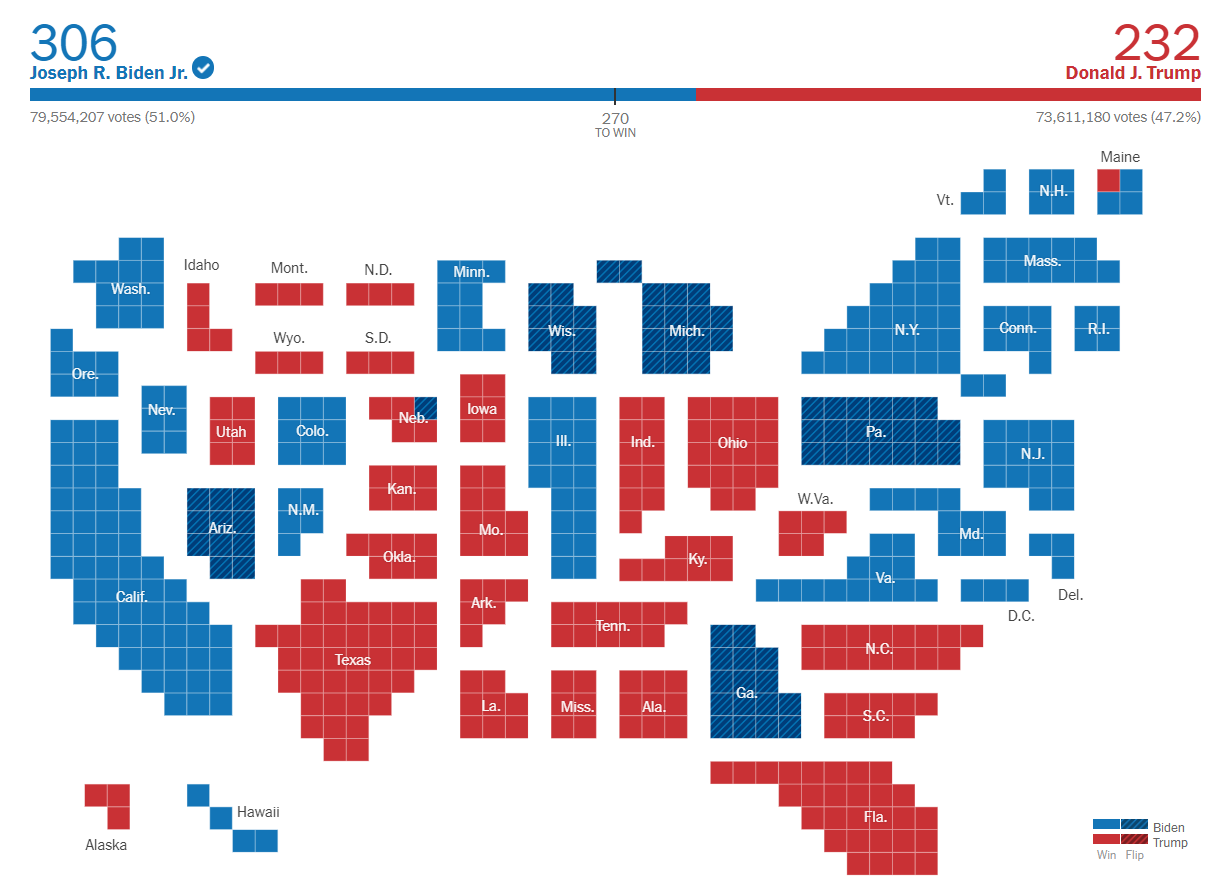

Now, however, the situation is different, aggravating existing shortcomings in the institution’s structure and procedures. Bipartisanism prevails in the modern US, operating across maleable yet distinguishable geographical and ideological lines. It is also unapologetic as never before. In this context, the Senate becomes a prime partisan battleground, often to the detriment of policy making. After all, it’s small numbers and expensive candidate campaigns mean that diverse or dissident voices have less of a chance to be heard and party discipline is enhanced. Split delegations are rare, while the majority and minority leaders reign supreme, most often being those who debate and propose bills. Still, there is more to it.

Consensus over bills and nominations has also been harder and harder to reach, hindered by procedural obstacles, namely the practice of filibustering. What was framed as a guarantee of free speech –as in Capra’s “Mr Smith”– enabling a senator to hold the floor indefinitely so long as they don’t sit down or yield, turned into a tool of minority obstructionism since the 19th century and is employed with redeemed rigour today. As a filibuster prolongs debate on a bill, it necessitates a vote of “cloture”, i.e. the end of debate, before the bill can be voted on. This raises the passing requirement from a simple majority to a supermajority, currently set at 3/5 or 60 senators. However, such a number is difficult to align in a partisan duopole, where a party rarely gets 60 seats, which effectively kills out the filibustered bill. Pointedly, this practice was historically used by southerners to defend slavery in the 19th century and racial discrimination in the 20th, in what was termed the “Jim Crow” era. It is astonishing that due to such Senate workings no substantial minority rights bill passed until 1957.

Today, both parties use the tactic, when a minority. Nevertheless, it is still Republicans whom it mostly favours and who exploit it the most. Their Senate leader Mitch McConnell, for example, is notorious for imposing deadlocks on Obama legislative efforts, including welfare schemes. Upon examination, a historical trend appears in which the Senate gives conservative minorities a chance to hinder the majority’s policy making. For both Southerners of the past and Republicans of the present have had (in most cases) minority support, population wise. Sadly, what pays the price is American democracy itself, and many of the disadvantaged within it. Even though there are reasons to support mitigating mechanisms ensuring sufficient state representation in the federal system, the current state of affairs is evidently problematic. Deadlocks produce no solutions; debate in the senate has lessened, often substituted by background party leaders’ discussions; filibustering itself has become efficient even as a threat or a phone call. The conclusion is easily deduced: the Senate malfunctions and ways out are necessary. Although this doesn’t imply that it is a worthless institution or that it doesn’t carry out important political work, it does imply that it has a biased structure, contrary to the myth of the US as a beacon of democracy, and revealing of the inequalities and exclusions present in the vast state.

References

- Capra, Frank, et al. “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington”. VRT TV 1. 1939.

- Adam Jentleson. Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy. Liveright. USA. 2021.

- A history of the United States Senate. The Collector. Available here