By Phaidra Chrysostali,

Karamanlis decided that Greece belongs to the West and was looking forward to a closer relationship with Western European countries, as he was aware of the political and economic benefits of integrating into the European Economic Community (ECC). This shift in Greece’s foreign policy was evident after the Cyprus invasion, as demonstrated by the visit of the President of the European Parliament, Cornelis Berkhouwer, to Athens, whose purpose was to examine the conditions and possibilities of reviving Greek relations with the ECC. From Karamanlis’ actions we can realize that he wanted Greece to be more autonomous regarding its foreign policy and, out of fear of the events with Turkey, he sought multilateral agreements with European countries. He also attempted to restore Greece’s relations with the West, and rebuild them on a trusting ground from which both parties could benefit.

A point that we must not overlook is the fact that Greece’s request to become a member of the ECC was delayed until 1981. Why did it take so long for Greece to become a member state? From my point of view, the ECC had a set of values and principles that were very different from Greece’s reality during the 1970s. Greece did not only have to prove to be a trusting country and to comply with those values, but also to become an economy that would be considered as competitive in the international market, which was not the case during the 1970s. But in just a decade, Greece’s imports of goods and services marked a rapid growth from 2 billion to 14.36 billion, which until the 1990s kept growing. Similarly, Greece’s exports of goods and services grew from 1.04 billion in 1970 to 10.98 billion in 1980 and kept on growing for the following decades. It is evident that Greece had started becoming more similar to the Western countries after opening its economy to the outside world and changing its mentality from a nationalist and xenophobic country to a more open and outward looking one.

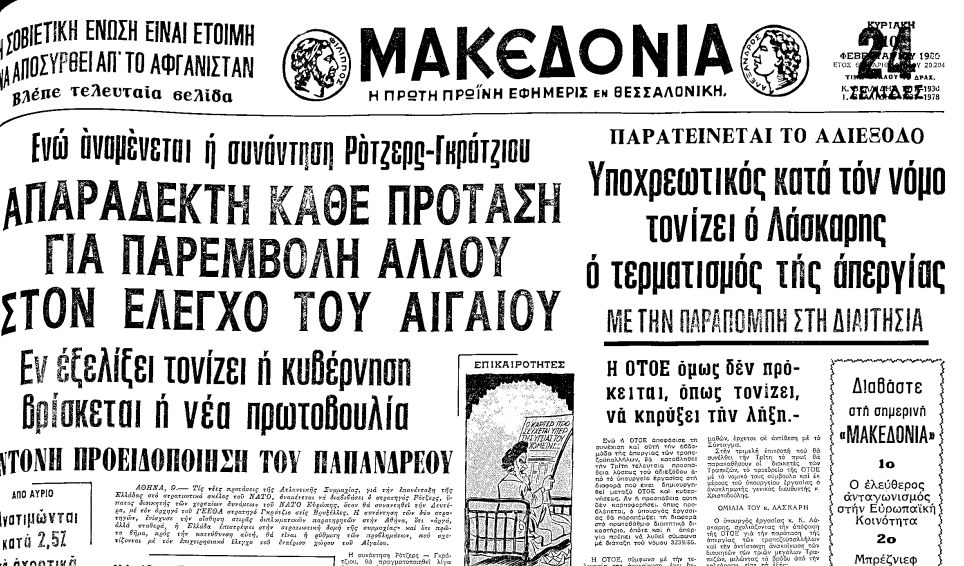

Another important dimension in the Greek foreign policy concerns its relations with the Balkan states, the effects of a patron-client system and cultural and educational changes. Regarding Greece’s relations with the Balkan states, in the analysis by Aristotle Tziampiris we understand that the partisan politics in Greece were proved to be contributory in the flawed handling of the Macedonian Question. But after Greece’s membership to the ECC there had been a policy shift which was more rational and pragmatic towards the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and other Balkan countries. By the end of the century, Greece has managed to become a reliable regional stabilizer and a developed civil society, even if its full realization is yet to be accomplished. Clientelism and corruption dominated Greece’s political parties as well as the society itself, a stance that differed from ECC’s principles. Even if Greece had evolved in many aspects of its foreign policy, corruption was a crucial aspect of Greek culture which held the country back from being on the same level with other Western countries.

In conclusion, Greece experienced dramatical changes during the Cold War years, which helped the state evolve to a crucial power. From the beginning of the Cold War, we can observe Greece being in a bad political position with many internal upheavals. It was a country accustomed to being “saved” from foreign interventions and ignored the reality that it could not survive as a state independently.

References

- Close, D. H. The originis of the Greek Civil War. Routledge. Oxfordshire. 1995.

- Brendan O’Malley, Ian Craig. The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion. Bloomsbury Academic. London. 1999.

- Reclaiming the Unredeemed: Irredentism and the National Schism in Greece’s First World War. CHARLOTTE. Available here

- James Edward Miller. The United States and the Making of Modern Greece: History and Power. Univ of North Carolina Press. USA. 2009.

- Greek Cold War anti-Americanism in perspective. OCLC. Available here

- Klapsis, A. “From Dictatorship to Democracy: US-Greek Relations at a Critical Turning Point (1974-1975)”. Mediterranean Quarterly. 22(1). 61–73.