By Phaidra Chrysostali,

Up until 1974, Greece had experienced a long period of political upheavals. Examining Greece’s historical evolution, we can understand that there was evident political dependency since 1832, when the boundaries and the monarch of the new state were determined over the heads of the Greek people by Britain, France, and Russia. This dependency was created due to Greece’s geographical position as well as its vulnerability due to its economic and political weaknesses. Therefore, given Greece’s vulnerability to foreign intervention, the instability that persisted in the international community between 1914-1949 turned out to be intensely disruptive for Greece. Greece’s participation in both World Wars caused internal conflicts that evolved into civil conflicts, which shaped domestic politics in various ways. Junta was the starting point from which Greece faced many difficulties, including the Turkish invasion in Cyprus in 1974, which provoked radical changes in its foreign policy during the Cold War years.

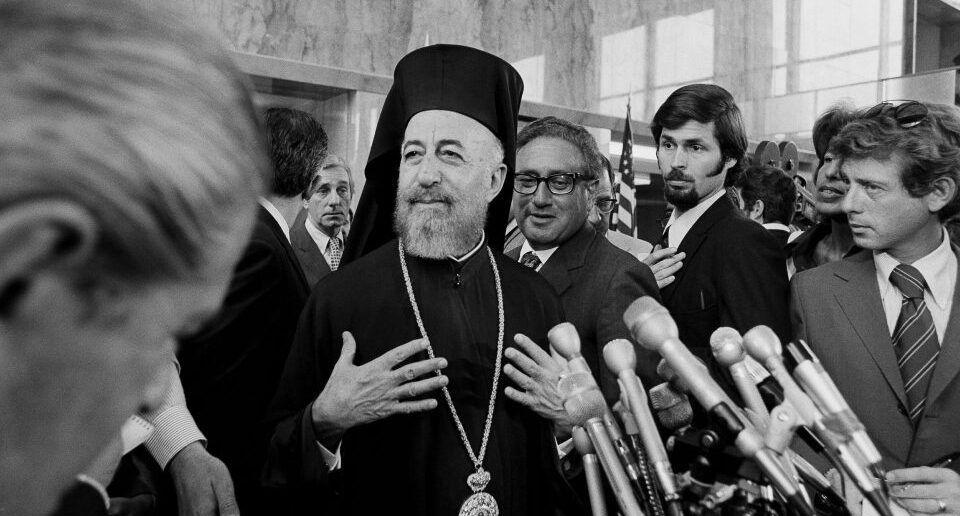

As we mentioned before, the 6-year period of the Junta is a period that most Greeks who experienced it would like to erase. The most horrific part of this dictatorship is considered to be the thousand fatalities and the invasion of Cyprus by the Turks. For the evolution of the events, we cannot blame anyone but the Greeks, since the Greek military dictators in Athens staged a coup in Cyprus in order to remove the Greek-Cypriot leader, Archbishop Makarios, which led the Turks to retaliate and seize a large part of the island. The Turkish invasion came as a surprise to the Greeks who had always believed that Cyprus would eventually become part of Greece and the irredentist ideology, Megali Idea, would be completed. The Cyprus humiliation led to the fall of the military regime, which marked a national disaster for the Greeks and also led them to the beginning of a remarkable renaissance.

During this time, we observe a state that has experienced a terrible loss of territory, developed strong anti-American sentiment, and realized the need to become an independent, from foreign invasions, state. Greek newspapers were describing Greece as a lonely state. More precisely, the newspaper Eleftherotypia stated: “We have always been alone. Without real allies, without loyal friends. Alone we have to face our enemies, alone we have to fight, alone we have to be sacrificed.” It is evident that the Greeks laid the responsibility for the events to other countries instead of realizing that they were to blame for the consequences of their actions. The removal of responsibility for past negative events from the Greek government and laying it to other countries creates a xenophobic environment and behaviors.

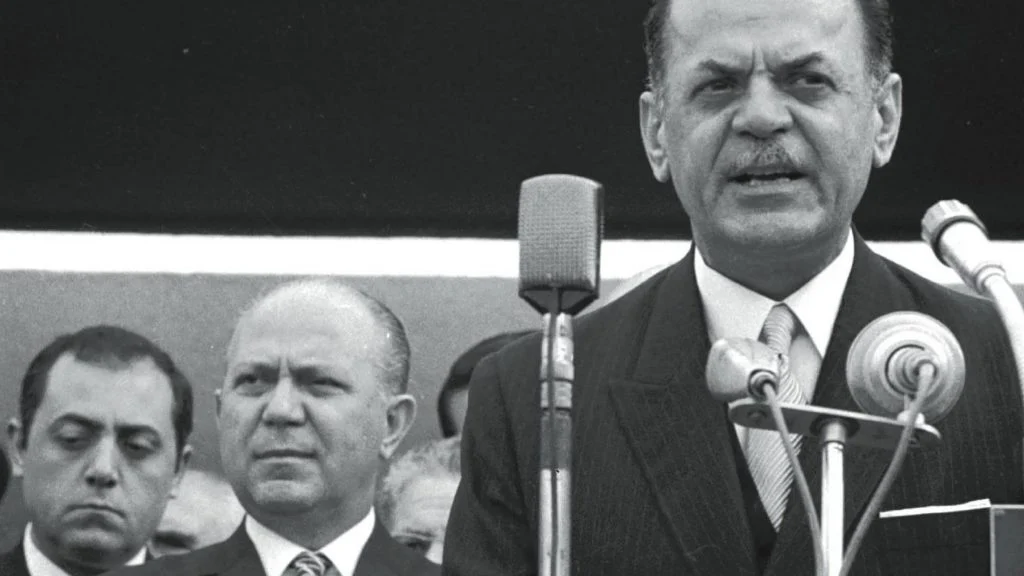

Accordingly, when in July 1974 Konstantinos Karamanlis came back to power to restore democracy (metapolitefsi), he had to deal with enormous problems, such as the restoration of democracy, confrontation with Turkey as well as uniting the Greek community. For the part of uniting the Greek community, his first action was the legalization of the communist party, which brought huge internal relief since they had been treating communists as if they were criminals. In addition, by legalizing the communist party, he made Greece a democratic regime where people had the right to vote the party that best suited their beliefs.

On the other hand, Karamanlis was in a difficult position regarding Greece’s relations with the U.S., because he had to satisfy the needs of the public opinion. Therefore, after the second offensive operation in Cyprus by the Turkish government, with no reaction from NATO nor the U.S, Greece withdrew from the military structure of NATO, even though its participation in the political activities of the alliance was continued. This reaction was an act of revenge against Greece’s allies, but in the long-run, it’s safe to argue that it was a dangerous decision for Greece’s security since NATO provided protection to Greece against dangers from the Warsaw Pact.

References

- Close, D. H. The originis of the Greek Civil War. Routledge. Oxfordshire. 1995.

- Brendan O’Malley, Ian Craig. The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion. Bloomsbury Academic. London. 1999.

- Reclaiming the Unredeemed: Irredentism and the National Schism in Greece’s First World War. CHARLOTTE. Available here

- James Edward Miller. The United States and the Making of Modern Greece: History and Power. Univ of North Carolina Press. USA. 2009.

- Greek Cold War anti-Americanism in perspective. OCLC. Available here

- Klapsis, A. “From Dictatorship to Democracy: US-Greek Relations at a Critical Turning Point (1974-1975)”. Mediterranean Quarterly. 22(1). 61–73.