By Katerina Taxiaropoulou,

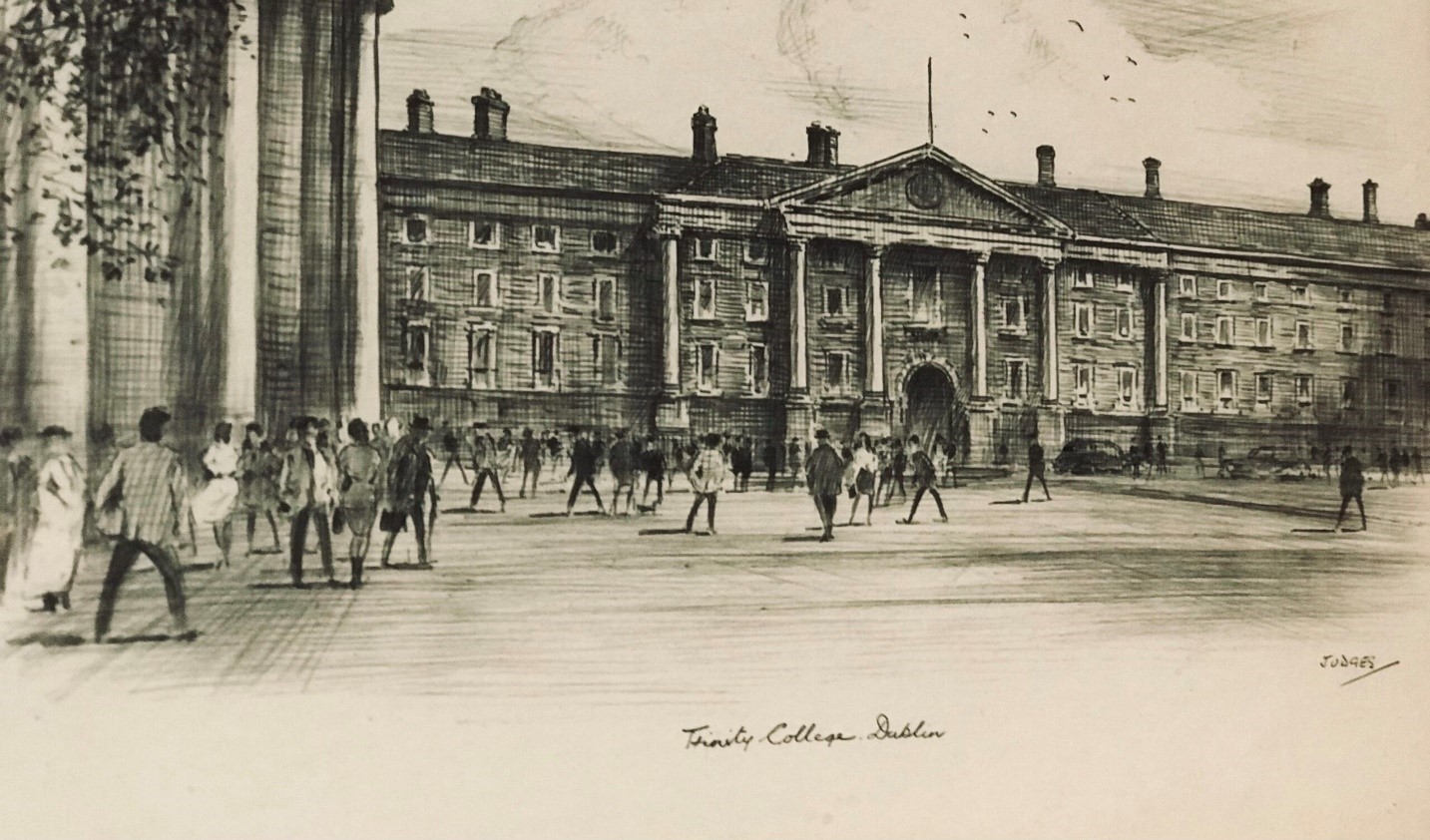

A capstone of the British rule over Ireland, Trinity College was founded by Queen Elizabeth I, who, in 1592, issued a royal charter for the establishment of an Irish college, modelled after Oxford and Cambridge. The name contained in the original charter was “The Provost, Fellows, Foundation Scholars and the other members of Board, of the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin” and it is used to this day in all legal documentation relating to the college (“Legal FAQ”). The new foundation was grounded in the lands and the dilapidated buildings of the Monastery of All Hallows, which, at that time, was laid outside the city walls, hence the title ‘near Dublin’.

During the first fifty years from its foundation, the community of Trinity grew, as more and more land endowments and fellowships were secured. Statues were framed, books were acquired, and a curriculum was formulated. This rapid advancement however was halted during the two civil wars. In 1641, the provost fled, fellows were expelled by the Commonwealth authorities in the following years, and finally, in 1689, the college was “turned into a barrack for the soldiers of James II” (“The History of Trinity College”).

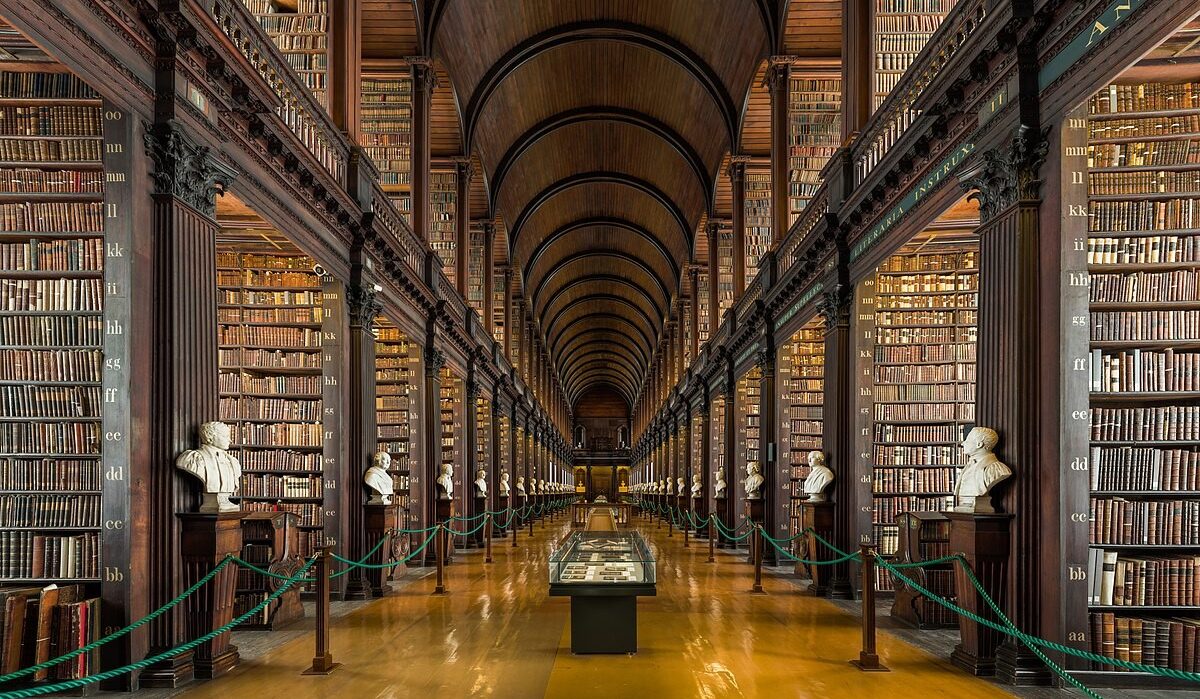

The 18th century was an era of peace for Ireland and so of great expansion for Trinity. As it was a university “of the Protestant ascendancy”, parliament viewed it with goodwill and made “generous grants” for building (“The History of Trinity College”). In 1712, the Library was built, and then slowly followed the Printing House, the Dining Hall, the Parliament Square, and, in the early 19th century, the Botany Bay. The most distinguished Irishmen who graduated from Trinity during the 18th century are philosophers and writers Jonath Swift, George Berkely, Edmund Burke, and Oliver Goldsmith.

During the 19th century, Trinity underwent a number of important changes, applied by Provost Bartholomew Lloyd. As a “determined if conciliatory reformer”, Lloyd introduced the modern system of honour studies, providing Trinity undergraduate students with the opportunity to specialize in mathematics, ethics, logic, and classics (“The History of Trinity College”). Within the second half of the century, a moderatorship in experimental and natural science was added, including physics, chemistry and mineralogy, geology, zoology, and botany. Finally, in 1856, a moderatorship in history and English literature was established. The most outstanding Trinity graduates of the 19th century were classical scholars Palmer and Purser, and, in mathematics and science, Rowan Hamilton, Humphrey Lloyd, Salmon, Fitzgerald, and Joly. Irish novelist, poet, dramatist, and critic Oscar Wilde also attended Trinity from 1871-1874.

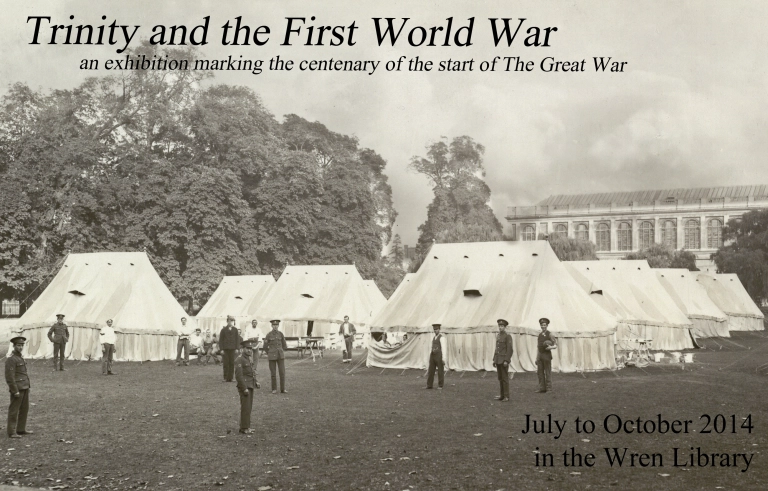

The start of World War I marked the end of an era of peaceful academic development for Trinity. As a part of the United Kingdom, Ireland entered the war in August 1914 along with France and Russia. These new circumstances of course led academic activity to a halt, as more and more students joined the army forces. During the Great War, “military khaki took the place of academic dress as the student population fell and the Colleges hosted officers in training, military conferences, and wounded soldiers” (“Trinity and the First World War”).

Just one year after the end of World War Ⅰ and as Trinity was slowly recovering from the major trauma, the Irish War of Independence started. According to official documents, 2.346 people died as a result of the conflict. Among the casualties were “919 civilians” and “491 volunteers” of the Irish Republican Army, which recruited many young Irishmen (“The Dead of the Irish Revolution”).

So, by the end of the Irish Revolution, Trinity found itself in a newfound Irish state, independent from the British rule, as well as grants. Lacking the necessary resources, the college struggled hard to maintain its position. It was not until fifteen years later that Trinity secured an annual grant from the State. This grant now represents “53 per cent of total recurrent income”, without considering research grants and contracts (“The History of Trinity College”).

Within the second half of the 20th century, Trinity became an increasingly international university, welcoming students from seventy countries, spread over six continents. This led to important changes, including “an increase of the representative element on the Board, in a radical recasting of the arts curriculum, in the erection of new buildings and the adaptation of old buildings to new needs” (“The History of Trinity College”). A leading figure in the field of Arts was experimental poet, short-story writer, dramatist, and director Samuel Beckett, who attended Trinity as a student from 1923–1927 and became a Doctor on July 2, 1959. Soon after, however, Becket “became despondent” and realized that he was “not suited to lecturing” (Samuel Beckett 1906-1989). Despite his distance from the college, Beckett’s work remains a steady component in the curriculum of Literary Studies.

Finally, the 21st century has been so far an era of adaptation to a rapidly changing world. Trinity College remains a prestigious highly competitive and research-leading institution. Whether one aspires to study there or not, it would be a great idea for them to visit the place and tour around the college’s campus and the historic library.

References

- The History of Trinity College. Tcd.ie. Available here

- Samuel Beckett (1906–1989). Tcd.ie. Available here

- Legal FAQ. Tcd.ie. Available here

- Trinity and the First World War. trinitycollegelibrarycambridge. Available here

- Eunan O’Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin. The Dead of the Irish Revolution. Yale University Press. Connecticut. 2020. p.544