By Dimitra Gatzelaki,

It was during the 20th century, the age of technological advancement, that the concept of the uncanny crept more and more inward, toward the recesses of the human psyche. Simultaneously, it also became subject to the cold, clinical gaze of psychology.

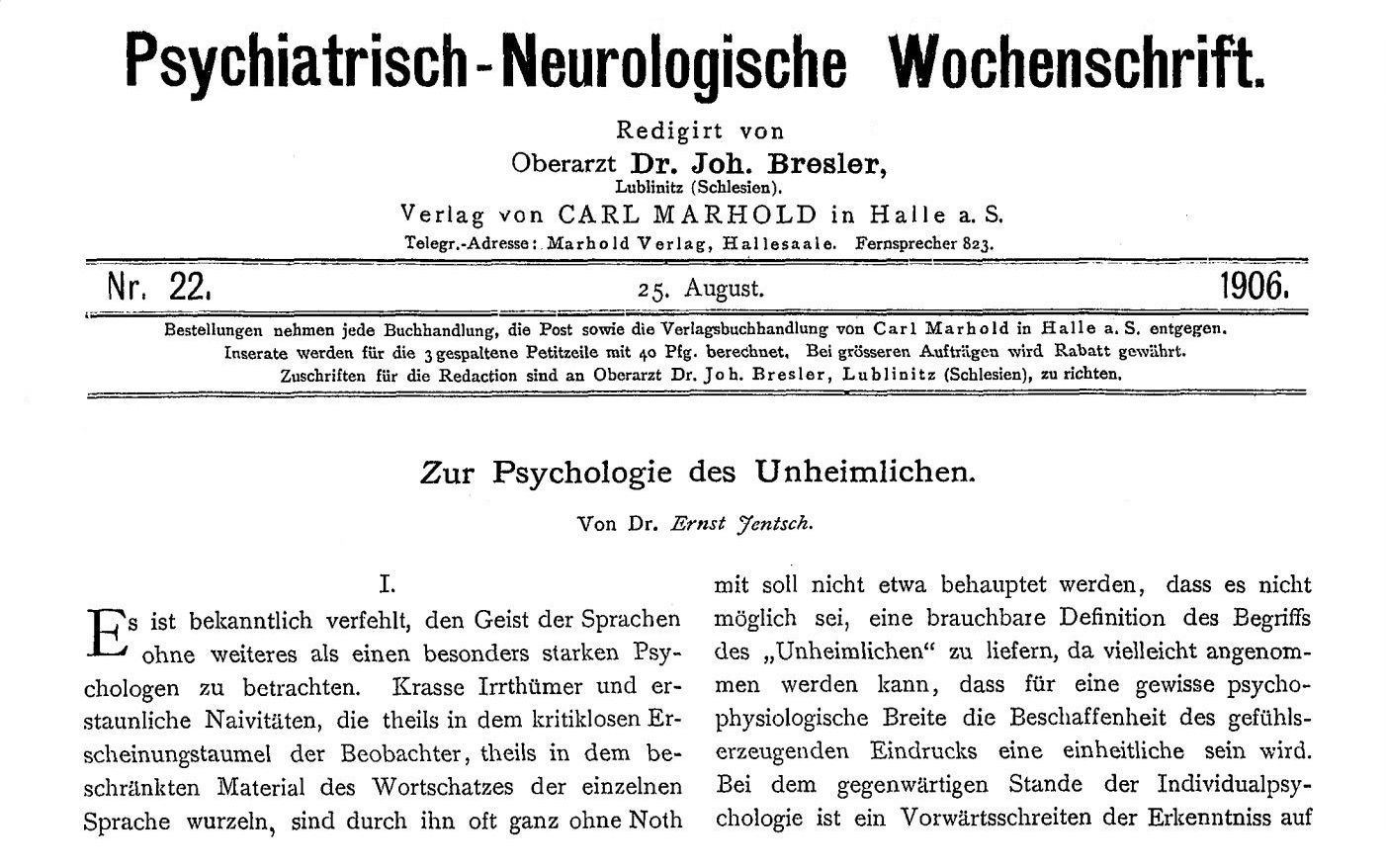

German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch is considered the pioneer in shedding a psychoanalytical light on the term in his 1906 essay On the Psychology of the Uncanny. Jentsch melded psychoanalysis with fiction, attempting to explain the latter scientifically. He delved into the horror of E.T.A. Hoffman’s short story The Sandman (1817) and concluded that, when narrating a story, one of the most successful devices for easily creating an uncanny effect is to “leave the reader in uncertainty whether a particular figure in the story is a human being or an automaton”, referring to the lifelike doll in Hoffman’s story, Olivia (qtd. in Freud). Generally, however, Jentsch saw the uncanny as being born from “intellectual uncertainty.” This does indeed tread close to today’s definition, where the uncanny is seen as the unfamiliar, the uncertain, that infiltrates the safe and familiar.

This “groundbreaking” distinction between familiar and unfamiliar was initially laid out by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. In his 1919 essay The Uncanny (Das Unheimliche), Freud expanded upon Jentsch’s (and others’) views, ultimately coming to popularise and redefine the term. Notably, he partially based his analysis on linguistics, drawing from the word’s etymology in German (his native language). Delving into German semantics, he uncovered the duality latent in the word “uncanny”, or “unheimlich” in his native tongue. “Unheimlich”, he writes, “is obviously the opposite of heimlich, meaning ‘familiar’, ‘native’, ‘belonging to the home’ “; thus, the uncanny is by definition the antonym of the familiar, the homely.

Through this linguistic excavation, Freud discovers a dormant yet fundamental truth: he says, “what is heimlich comes to be unheimlich.” More simply put, what was once comforting and familiar to us suddenly turns strange, and unsettling. Let’s consider for instance, our house, our family’s home, or somewhere where we feel at home; someplace familiar, homely, conjuring cherished memories. Well, one night, there’s a power outage there without warning, and we find ourselves in thick, enveloping darkness. Without light, without a means by which to see and recognize our home, the site of the familiar, this comforting familiarity fades into an unknown that is strikingly unsettling. Our home becomes unfamiliar, unhomely, and uncanny.

Rooted in the views of Jentsch, Freud, and others who have grappled with the concept of the uncanny (i.e., Jacques Lacan), the term has recurrently undergone (and is still undergoing) a series of evolutions and redefinitions, adapting to the anxieties and concerns of the contemporary moment. Recently, this evolution has thrown a new light on the uncanny. Today, the feeling is most often conjured in relation to technological advancement, particularly in the realms of AI, humanoid systems, and robots.

Listening to Siri on our phone can sometimes feel uncanny: despite lacking a physical body, it gives us the notion that we’re speaking to a living entity. In our minds, this blurs the boundaries between the real and the artificial, human and machine, muddling our understanding. This is closely related to Masahiro Mori’s concept of the Uncanny Valley. As technologies like Siri or even human-like robots (the Actroid, for instance) evoke human-like qualities in their responses and interactions with us, they fork an eerie path through the Uncanny Valley. As these responses can never be perfect, can never precisely replicate human behavior, we get a discomforting, uncanny feeling from them. In a sense, we can indeed view ourselves in them, yet that similarity takes on new, unfamiliar characteristics. Art produced by AI can also be viewed as uncanny: sometimes, its creations diverge from the normal output of the human mind, are bizarre beyond explanation, beyond understanding.

The uncanny, then, has been around us for a very long time, under a plethora of guises. Instead of disappearing, it evolves and migrates, aiming to unsettle the human mind to the greatest extent. As society progresses, the uncanny finds new issues and anxieties to latch on to; it thus disturbs and will disturb us perpetually, under different conditions, as any timeless phenomenon does.

Reference

- Cursed Images: A Short History of The Uncanny. Artland Magazine. Available here