By Carmen Chang,

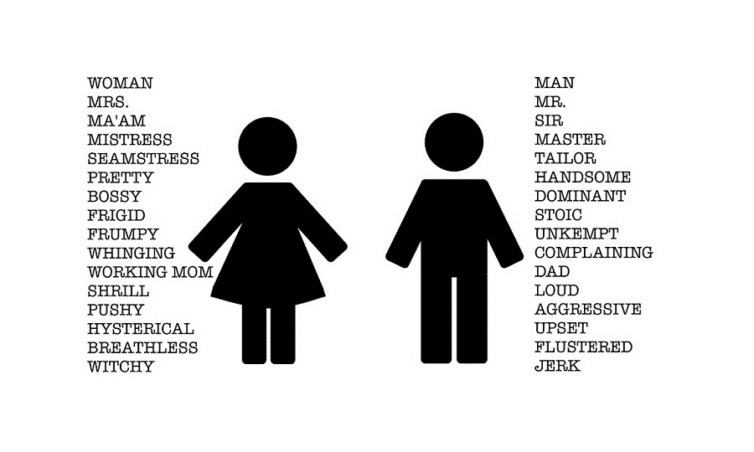

Linguistic sexism is applied both in the grammatical and ideological fields and in lexical terms. In my next article we will focus also on ideological issues. In the field of grammar, this phenomenon has to do with the exclusion of women when the generic and universal masculine is used, thus making invisible the feminine collective and perpetuating the masculine domain. As for the lexicon, certain sexist traits can be highlighted, since some terms in masculine highlight the superiority and qualities of men, while in its feminine sense, they have a pejorative and discriminatory connotation towards women.

In this regard, Leonardo Gómez Torrego, specialist in normative grammar and advisor to the Fundéu (Fundación Del Español Urgente), quoted by Mayte Rius (2014), insists on the distinction between lexicon and grammar:

“The lexicon must be politically correct, and changes can be promoted from society, especially by politicians, Tertullians and relevant people who can favour and promote changes in the use of words; but the grammar is aseptic, has some rules of masculine and feminine gender, of singular and plural, of verbal times, etc., that we cannot change by force, but evolve over time, slowly,” he says. Therefore, both Gómez and Bosque reject the proposals of non-sexist language guides that violate grammatical or lexical aspects of the linguistic system”.

According to Sandra Roubin (2017), sexism is also impregnated in the French language and this is visible in its operation, its grammar “male absorption of the feminine“, its semantic asymmetries “inequality of meaning between a masculine word and its feminine counterpart“, her contempt for women “see the plethora of abusive terms used to designate women“, the social identification she attributes to women “defined by the father or husband” and, in the case of dictionaries reflecting sexism, in terms that devalue women:

“During the 17th century, a wave of grammatical rule changes appeared, which in many cases favoured the male gender over the female gender when grammarians suddenly decreed that the male gender was more noble than the female. These sexist French language reforms were part of the power relations between the sexes at the time. In grammar, the rule «the masculine prevails over the feminine» resonates in us since our early childhood. It is the one we learned at school and that we apply mechanically in all our turns of phrase”.

To conclude this section, we can add what María Márquez (2013: 49) said in her book Grammatical Gender and Sexist Discourse:

“In the burning social controversy about linguistic sexism, certain academics, who speak in the name of “grammatical, or lexical aspects firmly established in our linguistic system” (Bosque, 2012), discourage intervention in the language for political purposes, such as ensuring equality in the symbolic representation of speakers regardless of their sex. Apart from the fact that the councils of the Guides on a non-sexist use of language are not directed to the everyday language, but to the administrative sphere (cultivated language, not natural language, as Moreno Cabrera points out, 2012), academics seem to forget their own conviction, that language cannot be changed by decree. That being the case, there are no reasons for fear or catastrophism, nor for ridicule, parody and even insult, which are noticed in certain criticisms of the guides who are accused of “ignorance” or lack of “deep knowledge of the referential act” (Manifesto of support for I. Bosque, 2012). But it does not meet our objectives to reveal only the argumentative fallacies that are used against the aforementioned guides in documents […], which use arguments such as presenting their own ideas as “unobjectionable” and “absurd” the contrary principles before having reflected on the subject (petitio principii, Lo Cascio, 1998); relying on the authority granted by the academic representative (argumentum ad verecundiam); or converting the defense of a thesis into that of a person (argumentum ad personam) strategies more typical of a television talk show than of an academic discussion. From the outset, I would like to point out a prejudice underlying all these criticisms: it is forgotten that the language, in addition to an object of study, is above all an instrument of communication created by a speaking community to satisfy its communication needs”.

Linguistic sexism: grammatical aspects

We will begin this heading by defining what gender is, since, according to the RAE, words have gender, but not sex; instead, animated beings have sex, but not gender:

“In grammar it means ‘property of nouns and of some pronouns by which they are classified into masculine, feminine and, in some languages, also in neutral’: ‘The pronoun he, for example, indicates masculine gender’ (Casares Lexicography [Esp. 1950]). Spanish nouns can be masculine or feminine. When the noun designates animated beings, the most common is that there is a specific form for each of the two grammatical genera, corresponding to the biological distinction of sexes, either by the use of distinctive gender suffixes or disinfections added to the same root, as in gato/gata, profesor/profesora, nene/nena, conde/condesa, zar/zarina; or by the use of words of different root according to the sex of the referent (heteronym), as happens in hombre/mujer, caballo/yegua, yerno/nuera; however, there are many cases in which there is a unique form, valid to refer to beings of either sex: this is the case of the so-called ‘common nouns in terms of gender’ ( a) and the so-called ‘Epicene nouns’ ( b). If the referent of the noun is inanimate, the normal thing is that it is only masculine (cuadro, césped, día) or only feminine (mesa, pared, libido), although there is a group of nouns that have both genders, those traditionally called ‘ambiguous nouns regarding gender’”.

In the case of Spanish, we can add what María Márquez (2013: 38-49) said in her book Grammatical Gender and Sexist Discourse:

“In the case of gender, from the origins of our language [Spanish], the tendency to the appropriateness of grammatical gender and the trait of ‘sex’ in the case of personal reference nouns is visible. Along with a worker, infanta, parturient or president, who did not exist in the first centuries of our language, have also emerged steward or couturier. But one thing is the spontaneous use of speakers, and another is the recognition of certain linguistic structures as correct, or the acceptance and entry of certain voices into the dictionary, facts that belong to another plane: the act of institutionalization that establishes the uses and sanctions them as correct. Three aspects that should not be confused: research on the functioning of the system, the ‘correct’ or normative application of that system decided by certain institutions, and the spontaneous use of speakers, creators, and users of a language whose ultimate objective is to satisfy their communication needs”.

In this regard, we can mention the highlights of the Cervantes Institute (2011: 136) in the Guide to non-sexist communication:

“This first part of the guide focuses on the use of language at the grammatical level and therefore addresses the language forms themselves. The aim is to highlight how it is possible to avoid ambiguous or sexist uses in the Spanish language in the words referring to women and the activities they perform. To this end, the general rules for the formation of the feminine gender in Spanish in nouns referring to persons are first recalled […]; secondly, reference is made to the so-called «generic masculine», grammatical form that constitutes the most criticized linguistic discrimination procedure, and both the non-sexist contexts of the generic masculine are observed […] as well as the sexist uses and contexts of the generic masculine and the general recommendations that allow to avoid it […]. To do this, all the graphic and morphological alternatives appropriate to the standard and use are collected. The suggested solutions to avoid linguistic sexism or ambiguity are intended to be natural and coherent, aim to reflect the most widespread forms among speakers and try to avoid forced or inappropriate formulas”.

In the case of the French language, for example, we can observe what Sandra Roubin (2017: 5-7) argues in the analysis “Sexism in the French language”, where she specifies that in grammar the masculine predominates over the feminine:

“In grammar, the rule «the masculine prevails over the feminine» resonates in us since our early childhood. It is the one we learned at school and that we apply mechanically in all our turns of phrase. As has just been said, it was therefore introduced in the seventeenth century, like a plethora of others to which we will return in the following points: the invariability of the present participles, the imposition of the masculine in the case of the attribute pronoun in the singular, the ‘adverbialization’ of adjectives (or less roundly called masculinization), as well as a certain conception of the formation of female nouns (which “would flow from the masculine”). The rule that the masculine prevails over the feminine prevailed in the 18th century. Today, despite the disappearance under the Third Republic of its hierarchical formulation in grammars following the demands of the feminist movement of the time, it is still used by teachers and is still very present in the representations and discourses of users. [… ] In the seventeenth century, the will of the reformers (especially Maupas in his French Grammar) to impose the masculine in the case of the pronoun attribute to the singular (the), while the female form exists (the). We still speak that way today”.

References

- El sexismo que ocultan las palabras. LA VANGUARDIA. Available here

- Le sexisme dans la langue française. agir par la culture. Available here

- María Márquez. Género gramatical y discurso sexista (Perspectiva Feminista). Editorial Síntesis, S. A. Madrid. 2013.

- Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. Real Academia Española. Available here

- Instituto Cervantes. Guía de comunicación no sexista. LENGUA VIVA. Queensbridge. 2021.

- Leopoldo Valiñas and MÁRQUEZ María. La Evolución del Lenguaje (1a parte). Editorial Síntesis. Madrid. 2013.

- Le sexisme dans la langue francaise. FSP. Available here