By Dimitra Gatzelaki,

One could very well claim that, in the 21st century, there is not truly any “new” story left to tell. All narratives, from classic to contemporary ones, are visited and re-visited by authors, until every story has been told in a myriad different ways. This is a point that has for a long time been hotly debated in the field of philosophy, as well as, in literary and cultural theory. Until Roland Barthes, in his 1967 essay “Death of the Author”, set forth the idea that texts should be treated as separate entities and thus, set the groundwork for the term intertextuality, which was later coined and popularized by the philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva. Intertextuality as a concept lies in not viewing a text as self-sufficient, but rather as a complex web of influences past and present, of allusions, as a constant interaction.

If we adopt the concept of intertextuality, we notice, rather than a ceaseless narrative recycling, a mutual and vibrant relationship between texts. Today, texts don’t just build on other written texts, but allude to art, film, music, any product of our culture. This is the case of David Lowery’s 2021 film The Green Knight, adapted from the medieval (late 14th c.) chivalric romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by Unknown; besides the obvious borrowing of plot, The Green Knight is a beautiful example of intertextuality in general, where its creator speaks to other texts centuries apart.

Watching Lowery’s film, one of course understands its plot to be adapted from Sir Gawain and The Green Knight, while Lowery also chooses to utilize similar themes: first and foremost, the overarching theme of a mythical, haunting quest of supernatural nature, but also the interplay between temptation and the code of chivalry, as well as the challenge of maintaining one’s integrity and honor when their life’s on the line. Nevertheless, Lowery opts for placing Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in a more modern context when it comes to its characters and especially Gawain (who in the film is not a knight and thus, doesn’t deserve to be addressed as ‘Sir’). Sir Gawain of the 14th c. chivalric romance is knightly in every possible aspect and shows this from the beginning. When he volunteers in front of King Arthur’s (his uncle’s) court to fight the Green Knight, he does so not with arrogance but with humility:

“I am the weakest, I am aware and in wit feeblest,

and the least loss, if I live not, if one would learn the truth.

Only because you are my uncle is honor given me:

save your blood in my body I boast of no virtue;

and since this affair is so foolish that it nowise befits you,

and I have requested it first, accord it then to me!

If my claim is uncalled-for without cavil shall judge

this court.” (354-361).

On the contrary, The Green Knight gives us a more modern version of Gawain, which once again highlights the film’s intertextuality, as traces of characters from other texts speak through him. Lowery’s Gawain is just Gawain. He’s not particularly virtuous or outstanding in any way: he’s beset by self-doubt, almost crippled by unmet expectations looming above his head, “humanized almost to the point of being unlikeable” (E Temple). Perhaps what Lowery ultimately had in mind was to turn knight Gawain into your average modern Everyman, so simple and recognizable that he becomes relatable. Hence, The Green Knight takes some steps away from its source material to become wrapped up in an intertextual web and does so with success. Lowery’s film “absolves” Gawain of the knightly code of chivalry and transforms him into your average everyday guy, exposing him as someone with wants, fears, little cowardices. This Gawain is someone we all have come across before; even within our own selves.

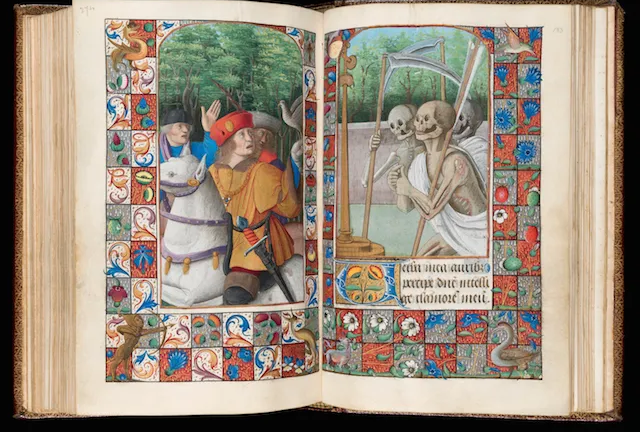

Yet, intertextuality in The Green Knight isn’t restricted to aspects of plot and characters: it abounds in the film’s visuals. Lowery and his cinematographer Andrew Palermo built scenes on color, shrouding the film’s ambiance sometimes in ochre, sometimes in red, blue and chiefly in green, painting a vivid color palette. Besides the obvious color symbolism that is in a sense intertextual (as it is imported from other texts and practices), The Green Knight’s visuals draw on medieval art and more specifically on illuminated manuscripts. Most often, these were religious texts handwritten by scribes and artists, intricately decorated with borders and illustrations whose vibrant colors (and fonts) have clearly inspired The Green Knight’s cinematography; it isn’t difficult to pinpoint the intertextual relationship there.

Lastly, Lowery himself has shed light on one of his major inspirations while directing his film: La passion de Jeanne d’Arc from 1928. He’s stated that Dreyer’s film used “incredible sets of medieval France … yet [Dreyer] chose to largely ignore them until the climax of the film and to tell the story entirely in close-ups” (N Marrone). This is something that Lowery emulated in filming The Green Knight to capture greater emotional depth, thus, initiating a relationship of intertextuality between the two films made almost a century apart.

All in all, intertextuality in The Green Knight succeeds at weaving a rich tapestry bridging past and present. Lowery’s inspiration, deeply rooted in medieval myth and art, classic cinema and modern visuals and archetypes, grafts a complex mosaic of inferences that transcends temporal boundaries. It is both wistful and ancient, while its modern elements simultaneously allow the viewer to resonate. Ultimately, The Green Knight leaves an indelible mark, with a cultural and emotional impact that can’t be ignored.

References

- J.R.R. Tolkien. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Barnes and Nobles. UK. 2021.

- The Green Knight Unmakes a Classic—to Unsettling and Glorious Effect. Lit Hub. Available here

- The Green Knight Director Reveals Which Movies Inspired His Adaptation. Screenrant. Available here