By Katerina Taxiaropoulou,

A torrent of the senses and spirituality, revolution and imagination, passion and death, euphoria and melancholic madness. Such was Romanticism when it first appeared in Europe towards the end of the eighteenth century. A literary movement that placed emotions over reason, Romanticism emerged as a reaction against the philosophy of the Enlightenment, which promoted “a mechanistic understanding of the universe” and prioritized a form of art that was more of an aesthetic than a political value (Partridge). Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) is the epitome of the Romantic political poet, as he used those elements of overflowing emotion and idealized revolution in his work to raise a polemical voice against the crimes of the British authorities. His sonnet, England in 1819, perfectly reflects Shelley’s liberal ideas.

Before attempting any analysis of the poem, it would be beneficial to provide some information about the heavy atmosphere in which it was produced. The English Romantic era was a “turbulent period” since it “saw social and economic changes” of great importance for people’s everyday lives (Attila 28). The Industrial Revolution came to overthrow the home industries of rural environments and create a new class of people, the laborers, who moved to mill towns. As a result of this shift, villagers without land property struggled really hard to make ends meet, while laborers were severely mistreated and exploited by their employers. Soon, a great division was formed between the capitalist and the laboring class, along with a widening gap between the rich and the poor. In this context, the less privileged ones gathered to demand their rights, leading to the escalation of the conflict on August 16, 1819, in Manchester, where the Peterloo Massacre occurred. According to Elma-Dedovic Attila, on that day “the authorities exercised control over people by violently killing and wounding the unionists protesting against the exploitation” (28). The title of Shelley’s sonnet alludes to this political tragedy.

The Peterloo Massacre affected many Romantic writers, among them, of course, the always radical Percy Bysshe Shelley. In response to the event, he wrote England in 1819 to make a vigorous attack on all British authority figures. In this fourteen-line poem, emotion overwhelms language, the latter being loaded with pejorative terms. First, Shelley addresses the king as a “blind, despised and dying” madman (l. 1), thus painting a picture of decay rather than a powerful monarchy. He then moves down a level on the hierarchical scale to attack the princes by referring to them as “dregs” and associating them with mud, thus indirectly commenting on their spoiled and corrupted nature. By using such derogatory words to criticize authorities, Shelley fulfills what Blazer considers an important requirement for a poem to be regarded as romantic: putting emphasis on emotion “over reason and rules,” and this in combination with a “tendency toward revolutionary politics” (3). Let us not forget the danger of directly attacking powerful men like Shelley did at the time.

The speaker moves on to compare rulers in general with leeches: “Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know/ But leechlike to their fainting country cling” (ll. 4-5). Here leeches, a type of blood-sucking worm, stand for those rulers who are blind to their subjects’ problems and profit out of their misery, sucking their blood to the point of them fainting. Next, Shelley accuses the army of killing people’s liberty instead of protecting it. Right before the climax of this harsh political criticism, the speaker comments on laws, which he characterizes as “[g]olden and sanguine” (l. 10). Golden because they serve only the rich and sanguine because they are killing the poor. Last but not least, the speaker attacks the institution of religion, which he characterizes as “Christless” and “Godless” (l. 11). This phrasing would be considered heavy blasphemy, without a doubt.

Notably, all these harsh and unforgiving words are put one next to the other with little use of punctuation, thus giving the impression that the speaker is running and cannot stop, a sense of breathlessness. John Keats who belonged to the second generation of Romantic poets together with Shelley, held that the poet is “only a vessel through which emotion flows” (Blazer 6). Indeed, Shelley’s exasperation here comes out as torrent. And it is unstoppable.

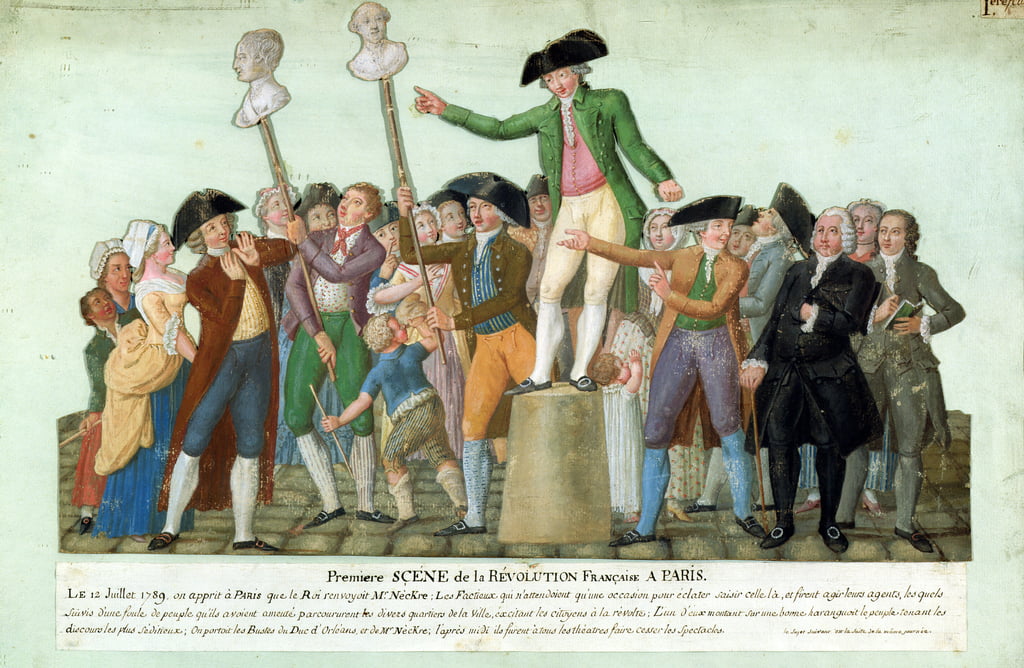

In this atmosphere of fury and despair, the readers are surprised by a sudden and unexpected turn to optimism. Shelley chooses the closing couplet to present what he considers the ideal remedy for the chronic disease of tyranny: Revolution. It is widely claimed that even though the poets at the time did not think of themselves as belonging to the same literary movement, which later came to be called Romanticism, they did share a common source of inspiration, which was the French Revolution and its ideals (Kipperman 188). For Shelley, the greatest ideal of all was that of social rebellion, which he introduces in the sonnet through symbolism:

- “A senate Time’s worst statue, unrepealed-

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day” (ll. 12-14).

Here, “Phantom” with a capitalized P stands for revolution and is considered “glorious” since it comes to “illumine” the tumultuous day of social uprising. Shelley associates revolution with light and, therefore, with a brighter future when the people will finally overthrow authoritarian political figures and institutions. These last two lines are quite explosive in their energy, contributing not only to the dynamic nature of the closing couplet as a kind of ‘volta’ in terms of tone but also to the force of the spirit of revolution.

Shelley was inspired by the rebellious uprising of the unionists who gathered on August 16th, 1819, in Manchester to protest for their rights. He saw an immediate link between revolution and political change. For this idealization of revolution, however, he was criticized. According to Kipperman, “Liberals as much as Conservatives could agree on the ‘impracticality’ of Shelleyan utopianism” and how “other-wordly” the alternative reality he suggested was (190).

All in all, Percy Bysshe Shelley was undoubtedly a revolutionary poet. Whether viewing his work as a powerful resistance to tyranny or as a futile idealization of revolution, one cannot deny neither the force of the emotion that overflows England in 1819 nor the radicality of the poet’s ideas.

References

- “Spontaneous Overflow of Emotion: The Blurred Heteronormativity of English Romanticism and Subsequent Necessity of Mary Shelley.” semanticscholar.org. Available here

- “Byron’s and Shelley’s Revolutionary Ideas in Literature.” semanticscholar.org. Available here

- “Absorbing a Revolution: Shelley Becomes a Romantic, 1889-1903.” jstor.org. Available here

- “Exploring the Inspiration for Romanticism: Was it a Counter-Enlightenment?”. review.gale.com. Available here