By Dimitris Kouvaras,

It requires little imagination to assume that a few days ago, on the cusp of December and January, every one of you would—in some way, festive or relaxed—have found yourselves welcoming the new year, 2024. Some of you would have celebrated the moment outside, participating in public festivities; some would have seen the fireworks from the comfort of your sofa; maybe a very few would have fallen asleep. What is certain, though, is that, sooner or later, you would have been aware of the fact that something has changed, at least as far as calendars are concerned, and a new year has begun.

In many cases, these changes of time that come and go are experienced with a sense of unambiguous self-evidence, as if they were woven into the very fabric of reality. After all, considering the case of the change of year, calendars are everywhere and determine pretty much every aspect of daily life, so it’s impossible to miss or not interiorize their count. However, what time is has nothing to do with the specific and contingent chunks we tend to divide it into, such as years, months, days, and hours, which figure in calendars and annual agendas. These aren’t but conventions that our civilization has developed for our orientation in the often-chaotic mix of senses and changes that make up our world.

Since the very beginning, the chunks that helped humans conceive of time were intimately related to astronomical phenomena, whose alteration had an obvious and repeated impact on the conditions here on Earth. Time after time, day and night succeeded each other in an apparently constant sequence. A colder period, during which land was underproductive, was repeatedly followed by a more fertile and then a hotter one until temperatures began to fall again and leaves started to fall anew. Nevertheless, the regularity of these changes remained unwarranted throughout most of the prehistoric period, which entailed acute existential anxiety. Rituals were used to tame and soothe it as a means of making sure nature behaved as expected. However, during historic times, the presence of calendars reveals that these changes have been inextricably integrated into our way of experiencing life as markers of an ordered and periodic change. The link with agricultural phases was especially important as a marker of their utility and, indeed, necessity.

Diverse types of calendars have developed throughout history. Their number of seasons, months, or days differed, and so did their starting point. For the Jews, it was the time when they believed the world was created based on scripture interpretation, estimated at around 3.760 B.C. Byzantine chronographers used a similar approach many centuries later. For ancient Greeks, the year one was when the first Olympiad took place, in 776 B.C., marking the establishment of a common cultural and religious identity. Specific dates would be noted based on the tenure of high-ranking officials, differing from city to city. Following a religious logic, the Muslim calendar starts with the Hijra, a pinnacle in the life of Prophet Muhammad, which corresponds to 622 B.C.

Despite their differences, these calendar systems had something in common. They relied on the motions of the sun and moon to define the above time periods and relate them to the agricultural circle and the seasonal weather changes. What’s more, they often missed the astronomical details, which caused them to slowly drift apart from the desired correspondence and created the need for adjustments. In many cases, this incompatibility was what rendered them obsolete. It was, in fact, what prompted the creation of the calendar we use today and with which we recently welcomed 2024.

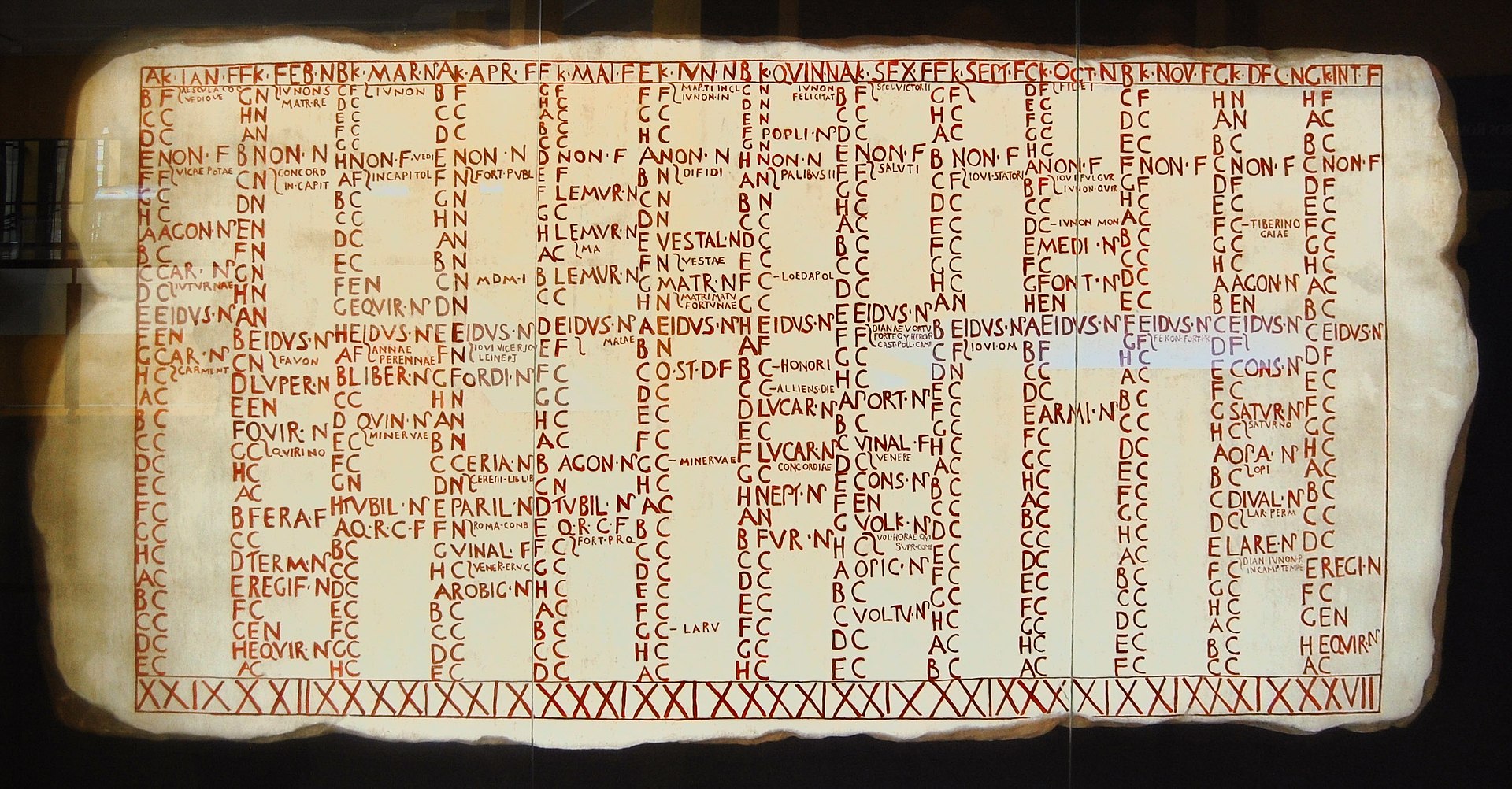

Its story begins with ancient Rome. The initial calendar was supposedly created by Romulus, the city’s mythical founder, and counted the years following the creation of Rome in 753 B.C. Again, it began with an important (but historically unconfirmed) date, consolidating Roman identity. What might sound weird about it is that it separated the year into 10 months, starting in March and ending in December. Some were named after gods, such as June, while others received names just based on their place in the sequence, like those from September (seventh) to December (tenth). Already in the 7th century, two new months were added: Januarius and Februarius, creating a new, extended lunar calendar, whose months except for Februarius would become odd-numbered in days since odd numbers were considered propitious. Still, this calendar drifted apart to an extent that required the periodic addition of an extra month to counter the deviation. Up to this point, each new year began in March.

Then came Ceasar. He demanded an ameliorated version, and Sosigenes of Alexandria, a renowned astronomer and philosopher, was his man. He devised the Julian calendar around 46 B.C., which included 365 days and a leap year every four years. It was now that January 1st was marked as the beginning of the new year, and the reason was practical. This adjustment served to align the year with the annual tenure of the two consuls, the highest-ranking officials of Rome’s executive government (until the period of the Principate). However, January 1st wasn’t celebrated as exuberantly as nowadays and neither became a universally accepted pinnacle, even within the Empire. It certainly did not become one for Christians, who preferred to celebrate the new year on certain feast dates. Yet the calendar stuck. It was, after all, impressively accurate astronomically, only deviating by 11 minutes every year.

Having in mind that the inception of the Julian calendar preceded both Christ and Christianity, one understands that it didn’t account for the birth of Jesus, let alone make it the pillar of its counting system. Still, it was adopted by the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 for the calculation of Easter in the recently Christianized Roman Empire. Until then, neither the mentioned chronologies nor the abbreviations B.C. and A.D. meant anything. That changed in the sixth century when a monk called Dionysius Exiguus created the system of counting years used to date, relying on a (mis)calculation of Christ’s birth. Even though his actual birth must have taken place before 4 B.C. (which makes the irony obvious) and the death of Herod, the convention was adopted. It remained in use along with the Julian calendar until 1582.

Remember those 11 minutes? By that time, they had accumulated to an extent that made important Christian holidays drift from their assigned dates. Pope Gregory XIII fixed this by encouraging the creation of the calendar we all use, which harmonises the year with the time it takes the Earth to complete a full rotation around the sun. The calendar was rejected by Orthodox Christianity for religious reasons until 1923 when it was finally adopted after certain modifications. Along with Western cultural and political influence, it has spread around the world and is now in use almost everywhere, although it often coexists with traditional calendars, such as in China.

Humanity finally has a universally standardised way of measuring time, but its story reveals its conventional nature. The fact that we live in a certain day of a certain month of 2024 is contingent, despite its immense grasp. However, it cannot be avoided easily. So, if you skip work tomorrow with the excuse that dates are conventions and it turns out bad, don’t blame that on me.

References

- “The new year once started in March—here’s why”, National Geographic. Available here

- “Why some people celebrate Christmas in January”, National Geographic. Available here

- “The Year One”, Essays, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available here