By Maria Koulourioti,

“Strength is the best aphrodisiac” he used to say and he acquired so much power that to this day he has managed to escape the wrath of the people despite his many misdeeds in Vietnam, Bangkok, East Timor, Bangladesh, Chile, Indochina, and any other part of the universe had the misfortune to become the object of his interest. He provided advice to twelve presidents, ranging from John F. Kennedy to Joseph R. Biden Jr., or over 25% of those who have had the position. Widely known as Henry A. Kissinger, he possessed a lifelong Bavarian accent that occasionally gave his statements an unintelligible quality, a deep reservoir of insecurity, a scholar’s grasp of diplomatic history, and the determination of a German-Jewish immigrant to thrive in his new home. As he passed away in November of 2023, it is interesting to view parts of his achievements, as well as his ambiguous roles in the tragedy of Cyprus.

To be particular, a scholar turned diplomat, Henry A. Kissinger oversaw the US’s opening to China, mediated its withdrawal from Vietnam, and used guile, ambition, and intelligence to reshape US-Soviet power relations during the height of the Cold War—sometimes at the expense of democratic values in the process. Kissinger passed away on Wednesday at his Kent, Connecticut, home. He was one hundred years old. Few diplomats have elicited such passionate admiration and revilement as Mr. Kissinger. Hailed as an “ultrarealist” who reshaped diplomacy to reflect American interests, he was also denounced for abandoning American values, particularly in the area of human rights, if he believed it served the interests of the country. He was regarded as the most powerful secretary of state in the post-World War II era.

Nixon’s most well-known foreign policy achievement was Mr. Kissinger’s covert discussions with what was still known as Red China. Originally intended as a decisive Cold War maneuver to isolate the Soviet Union, it cleared the way for the world’s most complex relationship—between the United States and the second-largest economy—which at the time of Mr. Kissinger’s death were completely intertwined and yet perpetually at odds as a new Cold War loomed.

The first significant nuclear weapons control accords between the two countries were the result of the détente talks in that he persuaded the Soviet Union to participate. He succeeded in deposing Moscow as a significant player in the Middle East through shuttle diplomacy, but he was unable to bring about a more comprehensive peace in the area. Furthermore, he shared the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for his work brokering the peace agreements that brought an end to US involvement in the Vietnam War, which he did over several years of talks in Paris. He referred to it as “peace with honor,” although thousands of lives were lost in the conflict, and detractors claimed he could have struck the same agreement years earlier.

On the other hand, we have a supporter of realpolitik (politics of power and oriented to realistic goals rather than ideological concepts and free from moral barriers), Kissinger did not hesitate to use secret communication channels and bypass the democratic processes of his own country, to create conditions of rivalry and exploit them in the interest not only of his country but also of his own. In a polemical piece written a year before Henry Kissinger’s passing, Michael Rubin, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, urged Kissinger to express regret to Greece and Cyprus for his part in the invasion by the Turkish forces in 1974.

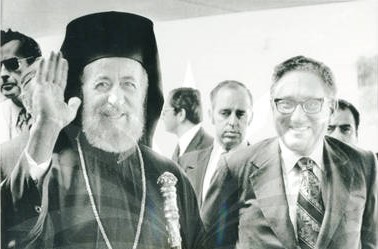

When Ioannidis attempted a coup in Cyprus, he must have felt confident of the outcome, not only because he had the support of the Greek Cypriot National Guard but also because he had the support of America (whose foreign policy had replaced British as the dominant one in the region), under the direction of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. But he failed to kill Makarios, only driving him into exile and replacing him with the far-right Nikos Samson. Turkey reacted by invading the island 5 days later, on July 20, 1974, occupying 3% of the territory. The junta in Greece collapsed with the second invasion in August where the Turkish force captured 40% of the island and Makarios returned to his shrunken territory. Population exchanges, acts of violence, disappearances of citizens, and the establishment of the Turkish Cypriot pseudo-state followed. James Callahan, the British foreign secretary, reports that Kissinger vetoed at least one proposal for British intervention to prevent a Turkish invasion.

Kissinger regarded Makarios as too independent and feared that if he expelled the military men responsible for the coup against him, communist influence would be too strong in Cyprus and he might turn to the Soviet Union to deal with the Turkish element. In his book “Years of Renewal,” he describes him as “the cause of all the tensions that will be caused in Cyprus”. It is also known that he regarded Makarios as the “Fidel Castro of the Mediterranean”.

Former Pentagon employee Rubin said in a piece for the Washington Examiner that Turkey is “now more of a liability to Western security than it is an asset.” Turkey is “now more of a liability to Western security than it is an asset,” according to Rubin, a former Pentagon employee. He added that Turkish aggression affects Greece, Cyprus, Iraq, Syria, and Armenia. Both domestically and internationally, Turkey persecutes religious minorities, and ethnic cleansing persists. In 1974, Kissinger deceived Greece and Cyprus and placated Turkey. Among other universities, Rubin has taught history at Yale, Hebrew, and Johns Hopkins. He disagrees with Henry Kissinger, whose efforts to pacify Turkey resulted in the invasion and occupation of Cyprus. He said that the choices he took back then “have greater consequences today than those surrounding the Vietnam War.” While hostility in Southeast Asia subsided over time, Kissinger’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean at best put an end to a situation that could have been resolved and at worst may have resulted in fresh hostilities.

Rubin recounted the tale of Kissinger’s efforts to placate Turkey both before and during the invasion of Cyprus in 1974 in an essay for the Washington Examiner. Kissinger’s actions demonstrated to the Turkish elite as a whole that aggressiveness is effective. Turkish authorities now think that Washington will bow to their size and ignore any smaller nation, regardless of how provocative they may be. Erdogan now thinks that using force may enable him to seize control of Greece’s Aegean islands, in addition to the fact that the northern portion of Cyprus is still the last area in Europe to be under occupation, he continues.

Rubin conceded, “Kissinger was wrong, and to right historical wrongs and deter new conflict, it will take crippling sanctions on Turkey, an end to the Cyprus military embargo, and further U.S. deployments in the Eastern Mediterranean.” Kissinger ought to apologize to Greece and Cyprus in the interim. The American historian argues that there is no better way to let Turkey know that its era of imperialism is coming to an end.

As he memorably stated: “The illegal we do immediately. The unconstitutional takes a little longer.” At peace may he rest. Greece however cannot afford to let her guard down and rest, and peace is a far from achievable conquest in a pile of “casus belli”. And for us, may we consume critically what is left behind us, to build ourselves a future.

References

-

Kokkinidis, T. (2023). Kissinger Owed an Apology to Greece and Cyprus – GreekReporter.com. GreekReporter.com. Available here

-

Sanger, D. E. (2023). Henry Kissinger, Who Shaped U.S. Cold War History, Dies at 100. The New York Times. Available here

-

Σαπαρδάνης. (2017). Ο ρόλος του Κίσινγκερ στην τραγωδία της Κύπρου – Ερανιστής. Ερανιστής.