By Maria Koulourioti,

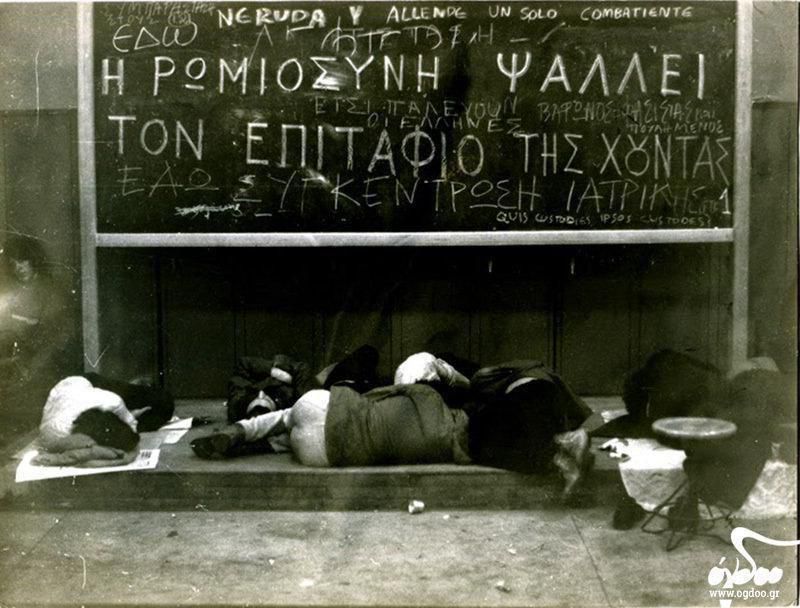

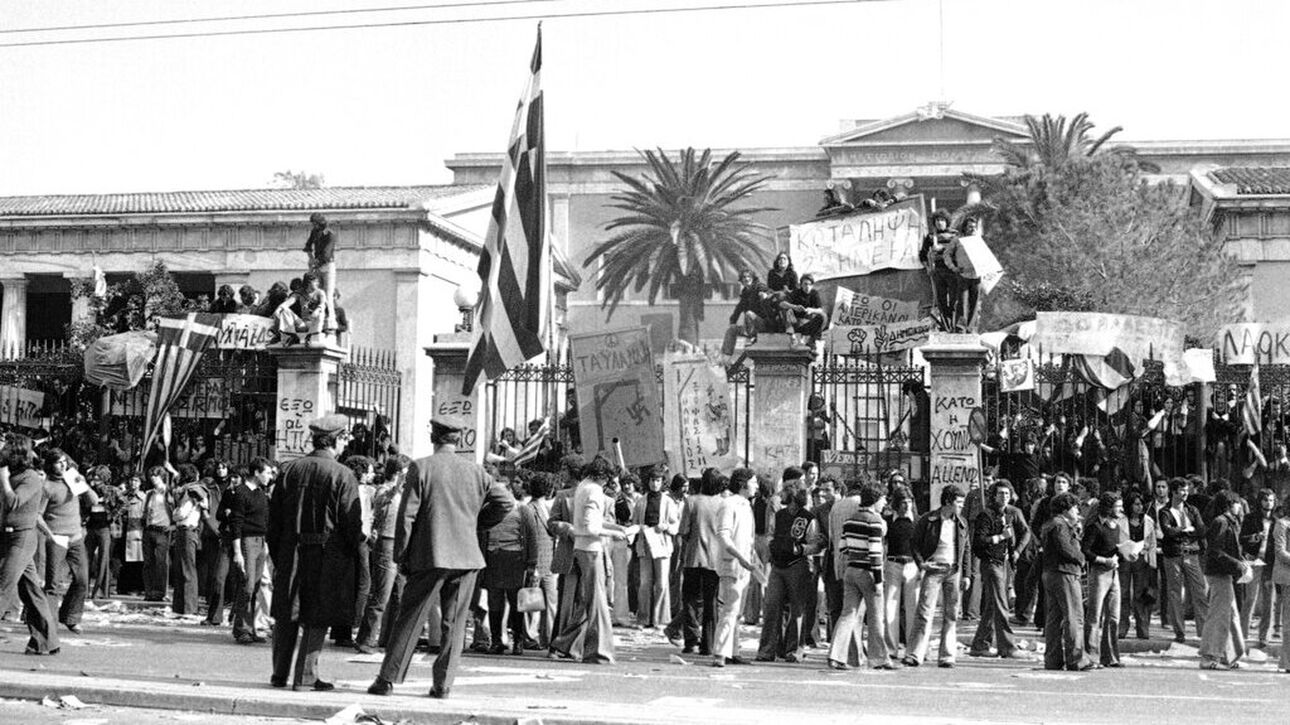

One of the noblest Greek holidays, the “Athens Polytechnic uprising”, or as we widely know it, the rebellion of Polytechneio, was a large-scale student protest against the Greek military dictatorship of 1967–1974 in November 1973. It started on November 14, 1973, and following a sequence of events that included a tank smashing through the Athens Polytechnic’s gates, it developed into an open anti-junta uprising that culminated in violence early on November 17. Whilst speaking of the sociopolitical impact frequently, it is equally important to discuss the cultural domino effect, as well as celebrate not only the artists but the bravery of the muses.

In particular, we are going to dig depper into the stories of the university student and poet Andea Frantzis, the journalist Alkmeni Psilopoulou and the professor of the National Technical University of Athens Tonia Moropoulou remember and talk about what they experienced inside the Polytechnic since the beginning of that week and especially the night when the blood of the innocent flowed abundantly, changing the modern Greece forever. These are three women’s testimonies that became “the poem” Mikros Timvos (November 17, 1973) by Nikiforos Vrettakos.

The poem, in translation from greek;

Without rifle and sword, with the sun on his forehead,

you were heroes and poets together.

You are the Poem.

Reaching out my hand doesn’t reach there

that nice flowers your forms

The air of virtue is litany. Oh my children,

In front of this poem, only silence counts.

Andea Franzis, in her own words mentioned: “I didn’t have a political role – active – at that time. During the dictatorship I had abandoned the university because of the climate in Philosophy, where there were always scumbags, and every day we saw people, our friends, children we knew, our colleagues, disappearing. From the first days, I had been active, going in and out of the Polytechnic. At some point each of us had to decide if we wanted to stay in or leave. I have decided that I am staying, but individually I would say. I have to say that at one point I felt that things were getting too hard and that I had to get stronger.

Policemen approaching, I naively said ‘I’m hit, I’m hit‘. The reaction was for them to grab me and start beating me against the car, the iron car until, apparently, because there was a tree and a pit next to it, I fell into the pit and the last thing I heard was that they said ‘Let’s go‘. It seems I passed out because it took a long time. I didn’t say a single detail, that these policemen who were beating me and who seemed to finally be scared that something had actually happened after I was beaten, cursed me very badly with sexual characteristics and with a phraseology that I don’t even want to repeat. Of course, on the way I discovered various comic tragedies.

The legacy of the Polytechnic for me is vigilance. That is, to always be ready to perceive what is happening, to follow the historical events, to be aware and active in them. We must always feel that there is nothing that guarantees us any certainty and that there is always a danger that democracy will be shaken, whether in everyday life, or in the economic crisis, or in the pandemic, there are always elements that can shake democracy and we must be constantly alert.”

In continuity of Andea’s courage and her painful-to-hear undergoing’s, Alkimeni Psilopoulou shares: “In my case, I entered the Polytechnic on the second day with a friend of mine. We had heard that some people had entered the Polytechnic, that there had been an occupation, but we did not know many things. At that time, I was organized in Riga Feraios, an act in the context of our anti-dictatorship struggle. Inside it was something like a celebration, there was a frenzy. That is, all these slogans, freedom, resistance to the Junta, were a festive atmosphere.

We then took our lives in our hands. It is a different attitude to life, a different attitude to political participation. It’s an initiative. It is a fight at the risk of our lives, but a fight in which we were all united in what we agreed on, despite the different opinions. And this is a timeless message because in every era democracy has to solve its problems and especially today it has to solve a lot of problems so that young people can have hope, have a job, have dreams. This is a big message and it is always a message for young people that in their own time, their own democracy they must shape it themselves.”

References

- Greece, C. (2021) Πολυτεχνείο: Τρεις αγωνίστριες θυμούνται τη βραδιά της 17ης Νοεμβρίου του 1973, CNN.gr. Available here

- Nikiforos Vrettakos (1973) – Μικρός τύμβος. Available here