By Dimitris Kouvaras,

Responding to Hamas’ deadly attack of October 7th, the Israeli Defence Minister inaugurated the exhaustive blockade depriving Gaza of all humanitarian supplies and vital goods, with the following brute statement: “we are fighting animals”. Bombings ensued. In times of crisis, when innumerable civilian lives are endangered by deprivation, disease, and death, it is imperative to understand the historical processes leading to the current paroxysm of the conflict. Only if not taken for granted will there be a chance of it being resolved, as insights are gained from the correspondences between past and present.

In the late 1930s, the British Mandate for Palestine was a ticking bomb. The Arab rebellion of 1936-1939 shifted British foreign policy, as the British pondered ways to keep aggression at bay. Lord Peel’s Commission in 1937, drafted the first partition plan envisaging separate Jewish and Arab states. It was deemed technically inviable and discarded for requiring enormous population displacements, especially of Arabs, who rejected the scheme. Another document, the White Papers of 1939, provided for a Jewish homeland within a Palestinian Arab state, effectuated within 10 years, and strict immigration controls. Further Jewish saturation would be unsustainable.

The Second World War changed all balances. The surviving Jews, enduring the horrid conditions of allied DP (Displaced Persons) camps, saw Palestine as their last and only refuge from the Holocaust ordeal and the harsh conditions in Europe. As guilt cast its shadow over both sides of the Atlantic, they began flocking to Palestine anew, albeit illegally. It was advertised by Zionists as an “empty land” waiting for its destined people. Albeit far from reality, the myth convinced immigrants and diplomats alike. Besides, it was convenient, as most borders in Europe and America were closed to Jews, providing no alternative destination for the brewing population displacement. Guilt wasn’t enough to outweigh the demographic and financial risks posed by a refugee influx.

Mandatory Palestine’s anti-immigration policy became unpopular, inciting sabotage acts by Jewish paramilitary, which had developed in the 30s. Jews were organised, unlike Arabs, who had been conceded no prewar elected assembly. Worn and tired, the British referred the issue of Palestine to the nascent United Nations in April 1947. The Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) proposed the infamous Resolution 181: partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state, as parts of an economic union, with Jerusalem under a special international regime. The patchwork-like borders granted the Jewish state 55% of the territory, including the fertile eastern region, most of the lucrative citrus plantations, and water reserves, despite Jews’ possessing only 10% of the land. The Committee, insensitive to local balances, largely decided on moral terms. However, as was to be shown, moral compensations are no match for resolving geopolitical matters.

The Arabs dissented, and so did the very British, who had abandoned the idea of partition ten years earlier. Still, it was put to the vote in November. Intense Zionist lobbying with the US and France, and President Truman’s affiliations shifted the tide of scepticism. Instrumentalising Thanksgiving, the US elicited certain small nations’ support by administering hefty federal loans; it was bribery. The USSR surprisingly adopted a pro-Jewish stance, wishing to infiltrate Palestine upon British withdrawal. That’s all it took for the resolution to pass. Its implementation was entrusted to the Committee and British supervision, without international military aid, in a “casual fashion of dismissing partition as a minor chore to be done by the housekeeper on the way out of the house”.1 The housekeeper were the British, and they would offer no help.

On 14 May 1948, David Ben Gurion proclaimed the Jewish state of Israel. Jewish paramilitary had begun cleansing the north-eastern plain by terrorising the Arab-Palestinian population to flee. War erupted immediately by Palestinians and neighbouring Arab states facing the emergent refugee crisis. Arabs in the coastal zone were instructed to evacuate until a victory that never came. Strategic misplanning led to approximately 700.000 being permanently displaced. Israel refused to rehabilitate them, annexing the entirety of the coastal zone. Jordan annexed the West Bank and East Jerusalem, while Egypt took Gaza. These became the remaining Palestinian hubs, as the geodemographic landscape of the region took its familiar form.

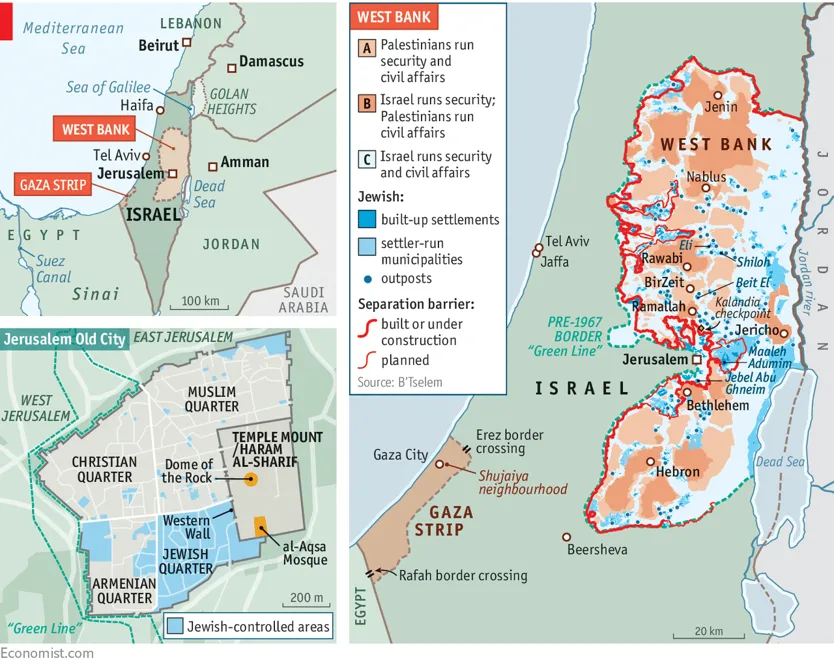

In 1967 Israel took to the offensive and captured the above territories in the Six-Day War. This geopolitical war on resources received ethnic and religious signification to the detriment of Palestinians, as Israel became the only arbiter. Ben Gurion’s sanctification of the secular Israeli state, its profound ethnic-national axis, and the growing influence of ultraorthodox Jews marginalised Palestinians ideologically and institutionally as outsiders, considered “non-citizens”. Religiously and politically motivated Jewish settlements began spreading in the West Bank and Gaza, competing with Palestinian communities. Gaza became a cheap labour hub for agricultural business, while movement controls were implemented. Living standards plummeted Palestinian resistance was undertaken by various guerilla groups, the most prominent being the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), founded in 1964 as a confederation of militia supported by neighbouring Arab states, to become a concentrated actor of representation. It also assumed political character, gradually mitigating the radicalism of its initial programmatic goals.

Meanwhile, a Muslim social charity partially subsidised by Israel, Mujama Al-Islamiya, was founded to support social infrastructure in Gaza. As the first Intifada sparked in 1987 it evolved into Hamas, a military group that, since the uprising’s culmination in 1991, began attacking Israel directly, as an illegitimate state. In response, Israel enforced a permit system monitoring all movement in and out of Gaza.

Israel and the PLO reached a settlement in the internationally brokered Oslo Accords of 1993, entailing mutual recognition, along with an autonomous “Palestinian Authority” (PA) as an elected institutional body with graduated jurisdiction over Palestinian territories, and plans for a final resolution. Hamas rejected negotiations as docile, and so did the rising factions of Jewish ultras and extreme-right politicians in Israel, including Benjamin Netanyahu, whose brother had died in a military mission responding to a Palestinian hijacking. Jewish settlements in Palestinian territories continued, and so did Palestinian attacks, which were avenged in many times the death toll. The PA was rendered powerless, delegitimised by Israeli disrespect for treaties and international apathy, or even by Arab radical elements. A second Intifada erupted between 2000 and 2005. Israel built a fence encircling Gaza and destroyed its port and airport, which aggravated living standards and triggered dissent. After the conflict, Israel withdrew all troops from Gaza but continued restricting movement to the West Bank in violation of the peace agreement. Hamas, now also a political player, had its best chance.

Amidst distrust for the bankrupted diplomatic avenues, it won the elections after the Intifada in 2006. Tensions rose with Fatah, the military-political party affiliated to the PLO, leading the Palestinian president to dismiss Hamas’ government. Armed conflict ensued, in which Hamas took power over Gaza, dismantling ties with the PA in the West Bank. Israel’s response was the comprehensive blockade of Gaza that has continued to date, fostering a profound humanitarian crisis. Extreme-right dominance in Israel, exemplified in Netanyahu’s administration, exacerbated the situation. This is the direct background of October 7th.

The primary lesson to be learnt is that suffocation breeds extremism, and so do unkept promises. Israel’s institutional parity to the West cannot legitimise the collective punishment of Gaza’s two million residents, even if extremism is involved, nor the West’s mild response. Another lesson is that, unless Palestinian emancipation be made possible, the conflict will continue. It’s not about Hamas: even if destroyed, someone will succeed it. What is needed is a permanent solution and no more western pampering.

References

- Martin Bunton, “Après nous le déluge: Britain, the United Nations, and the 1947 Partition Plan”, Journal of Modern Hellenism, 30

- “Israel at 75 – A nation in domestic crisis”, DW documentary. Available here

- “Gaza, explained”, Vox. Available here

- “Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s defiant leader”, BBC. Available here