By Terpsi Vasilopoulou,

The Mediterranean has always been a place of interest to the historians. Ever since the prehistoric times societies and civilisations have been developing around this fruitful sea, which was there helping them prosper, and left us with some of the most important evidence and information about humanity’s collective history. As societies developed around its realms and more complex relations started to occur between them it was not only beneficial and peaceful interactions but conflicts and disputes as well that began to multiply in the region.

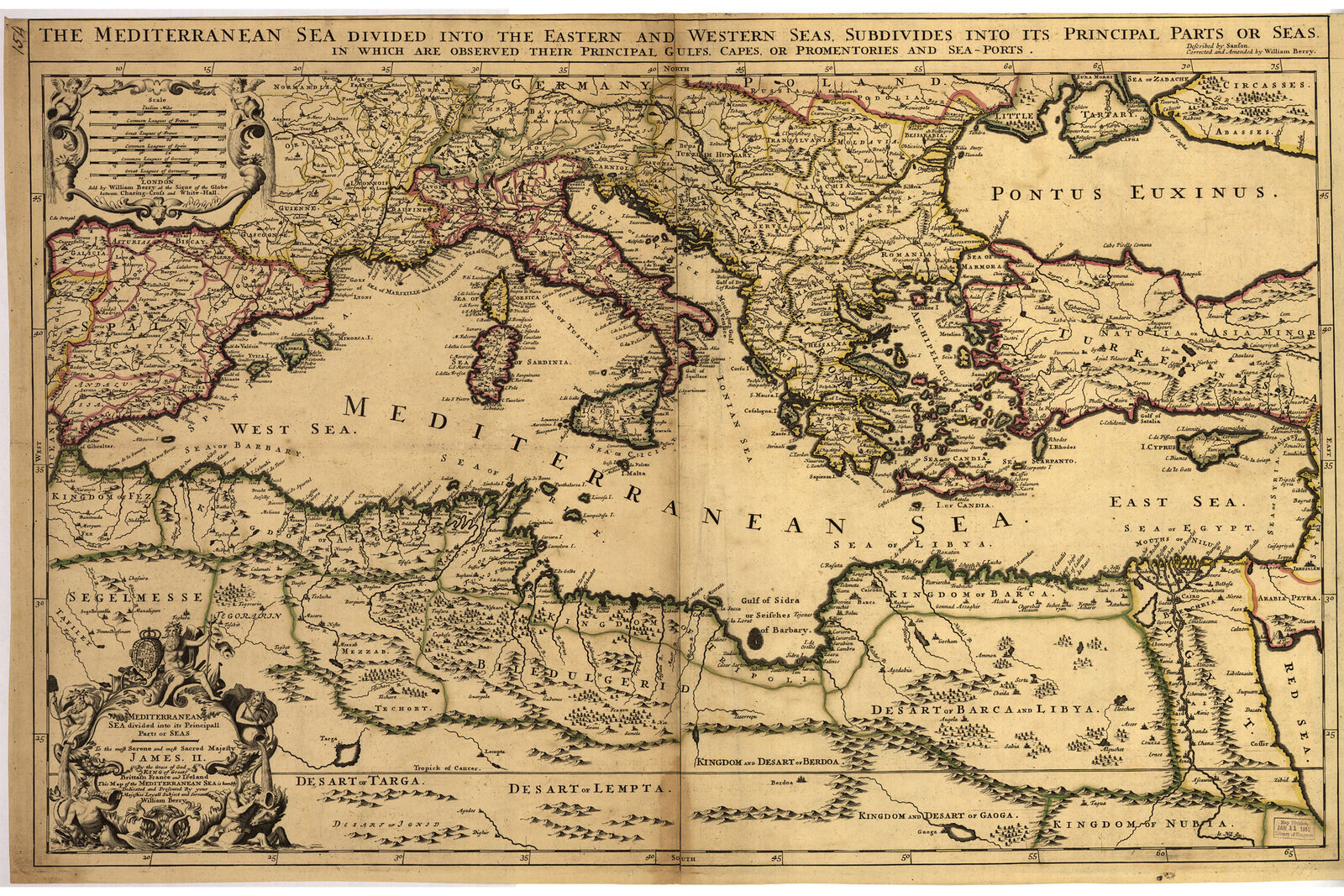

For many years historians have been occupying themselves trying to find a distinct definition of the Mediterranean as well as its characteristics. Was it a sea of unity, bringing civilisations and cultures together and creating multi-faceted societies where people from different backgrounds co-existed in peace and prosperity or was it a border dividing societies and creating conflicts over trade zones, economic privileges, and geographical expansion? Both opinions have been thoroughly supported by different historians creating multiple disagreements and schools of thought dividing scholars throughout the years.

Inspired by this historiographical debate, this article will be examining the two sides of the Mediterranean Sea, its nature as a frontier dividing societies around it, and as an intersection, to conclude which one was more dominant throughout the period discussed. The societies examined for this cause as the ones of greater presence and interest are going to be Islam and Muslim societies on one hand with Christianity collectively on the other.

Before diving into the impact of the Mediterranean Sea on the relationship between the civilisations built around it, it is important to first understand the definition of the terms frontier and intersection as used in historical research. As first used in France during the 15th century, the term frontier refers to a geographic or political area that faces, and lays next to a border. Unlike borders frontiers are vague and many times indefinite separating not only land and political entities but societies, cultures, or even classes as well. The term intersection on the contrary, according to the Cambridge English dictionary, refers to a point of junction. In our case a point where societies, cultures, and classes as well, blend, interact, and co-exist. The development of the Mediterranean frontier according to Reynolds can be roughly dated between the year 1000 when Normans had started to make pilgrimages from the English Chanel to Rome and the end of the century, when the Norman states of Italy and Sicily emerged. Ever since we can talk about the existence of a Mediterranean frontier affecting relations between civilians in and out of it with two main geographical points around which historians develop discussions, one in the east with the Byzantine Empire and one on the west with the Iberian Peninsula, both interacting with the Arab/Muslim world which occupies the biggest part of the southern Mediterranean region.

Undoubtedly the Mediterranean was a place of great conflict and many wars have marked the history of the region between the different Christian and Muslim communities inhabiting it with all entities wanting to grow their borders and population as well as dominate the sea. The greatest example of such conflicts are of course the Crusades.

In the span of approximately two centuries (1096-1291) five crusades, religious wars supported and initiated by the Catholic Church, took place in the Mediterranean region with Christian western powers collectively attacking the Muslims with three main aspirations: recapturing the Holly Land and especially Jerusalem after years of being under Muslim rule and repatriating the holly crux, protecting the Christians living in those areas from assumed Muslim hardships committed against them and strengthening the Christian European identity by achieving religious salvation and amplifying religious belief. All five of those bloody military campaigns resulted in a lot of pain and death for both sides while also worsening the relationships between Christian and Muslim entities both on a governmental and societal level creating hate and competition between the people and states of the Mediterranean.

The crusades did not only harm relations between the two religiously different sides of the Mediterranean but torn the Christian communities themselves as well. Great tension was created among Latin and Byzantine communities cause of different agendas and interests with none of their goals being achieved, resulting to the Franks attacking Constantinople after the end of the Fourth Crusade and the fall of the great city to Latin control on April 12th, 1204.

Furthermore, in the context of the joint campaigns, rivalries were sharpened; the personal rivalries of the leaders, national rivalries, the oppositions between the clergy and laity, and between the Latins and new crusaders arriving from the West created even more tension and a hostile climate among all the entities surrounding the Mediterranean.

Reasons for dispute and conflict, however, were obviously given not only by the Christian community but the Muslim one as well. Before the crusades, like every developing state with aspirations, Muslim communities wanted to expand on the Mediterranean region, grow their population, and advance their sphere of influence. Only two years after Muhammad’s death, Muslim armies with the guidance of the first caliphs invaded and conquered, in remarkably little time, the neighbouring and exhausted from previous conflicts states of the Middle East. After that, they turned to the west with their campaign against the Iberian Peninsula being almost successful till their course was intercepted by the Franks.

On the other side of the Mediterranean, tension really started escalating between Muslim communities and the Byzantine Empire with the siege of Egypt, a region of great importance to the Christian empire because of its nutritional needs and food consumption being highly dependent on Egypt’s wheat production, and not only. A few years later feelings of hostility peaked when Muslims unsuccessfully attempted to conquer Constantinople until they did many decades later in 1453, a development which later on brought relations between the two sides on a truly completely different level.

With all those conflicts and disputes against the neighbouring states, the Mediterranean Sea started being seen as a true frontier dividing enemies, inhibiting the growth of each entity and separating people and cultures rather than blending them together in a multi-faceted society around its region.

References

- Reynolds, Robert L. The Mediterranean frontiers 1000-1400. The world frontier.

- Kousoulis, P, Konstantinos D Magliveras, Panepistēmio Aigaiou (Athens, Greece). Tmēma Mesogeiakōn Spoudōn, Panepistemio Aigaiou (Athens, Greece). Department of Mediterranean Studies, and International Conference “Foreign Relations and Diplomacy in the Ancient World: Egypt, Greece, Near East” (2004 : Rhodes, Greece). Moving Across Borders : Foreign Relations, Religion, and Cultural Interactions in the Ancient Mediterranean. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 159. Leuven: Peeters, 2007.

- Pispirigkou, Foula. Ο Μεσαιωνικός Κόσμος . 3 . Vol. 3 . Athens , Greece: Γνώση , 1985.