By Eirini Tassi,

A quick look at the genealogy of punishment and justice shows that both concepts have gone through enormous transformations over time, being shaped by dominant schools of thought, and in turn shaping the substance of the criminal justice system. In the 19th century British Empire, Australia became an important penal colony in delivering such punishment, with various penal institutions getting established to host various (career) criminals and types of offenses. After the early 1800s, Britain decided to take a harder stance against offenders given the consistently high levels of recidivism, with young rural English folk often being sent to Port Arthur prison in Tasmania for petty crimes like stealing bread. The institution prided itself as a “correction” penal establishment for offenders, aiming to keep them away from crime once they get released. And yet, not only did recidivism persist, but inmates became so intensely traumatized that they were rarely able to re-integrate into society once released. Even fewer ever made it back to England. So, was this penological tradition of colonial prisons truly about “correcting” inmates, or was this narrative merely a façade to hide their desire for gruesome punishment?

Punishment: from physical to mental

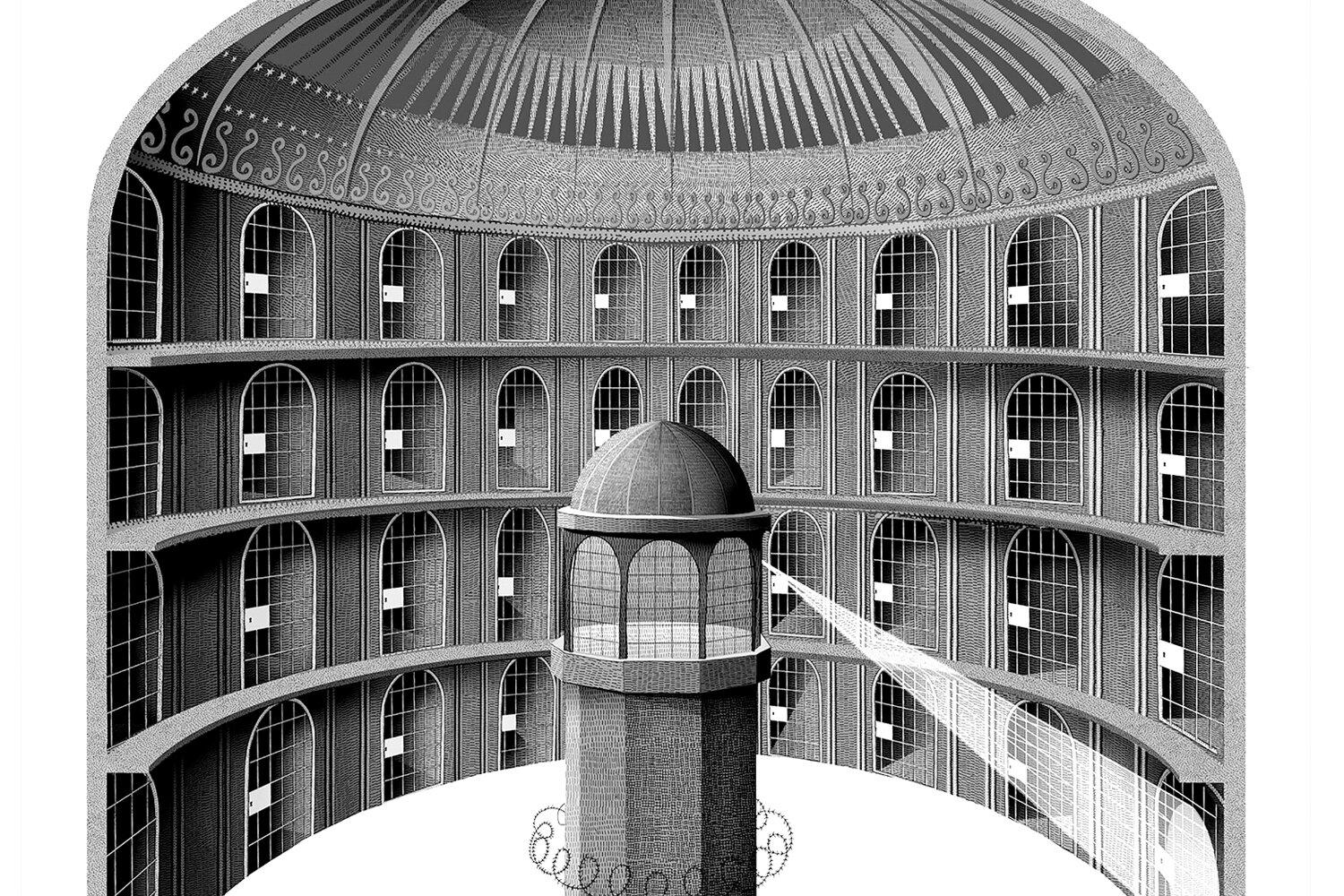

As Foucault describes in the opening chapter of Discipline and Punish, punishment in Western penology underwent a significant transformation in the early 20th century. Criminal justice moved from punishing the body, like via gruesome public torture, to “correcting” the soul through more gentle reformation, like subjecting inmates to strict activity schedules and constant surveillance. This was meant to push them into self-regulating themselves, their actions, and potential criminal urges, ultimately transforming into the individuals the criminal justice system perceived as “correct”. The ability of the penal institution to incur this unconscious self-regulation is, according to Foucault, its disciplinary power. Jeremy Bentham, a utilitarian and member of the prison reform, notably developed the idea of the panopticon, where a single guard tower in the center of a spherical space observed its surrounding cells, without inmates knowing if they were directly being watched at any moment or not. Bentham characterized this surveillance model as a “mill to grind rogues honest”, rendering it ideal for changing delinquent behavior permanently, as self-regulation and transformation will ultimately come directly from their soul (shame that he did not live long enough to read 1984). And yet, one of its prisoners from the 1870s, Austin Bidwell, characteristically stated that “an English prison is a vast machine.. move with it and all is well. Resist and you will be crushed”. This implies that a transformation of the soul did not come as deliberately and unconsciously as Bentham presents it; it rather appears more like a method of adaptability and survival. Concomitantly, the normative standard of normalcy and “correctness” inmates must abide by is set by an epistemology of human sciences, which work symbiotically with criminal justice to determine who needs and doesn’t need mental alteration in society.

In practice: “correction” turns to criminogeneity

Undeniably, the above instrumental construction of “correction” makes its narrative for gentleness and human-centric reformation a bit more suspicious. Even more so when looking at it in practice, in Port Arthur. The prison built a unique wing in 1848, the Separate Prison, which incorporated many penal reformist techniques of psychological “correction”. Inmates were locked in individual cells for 23 hours per day and the building was governed by a regime of silence. Inmates were not allowed to talk to one another, and even mats were placed on the prison floors so that footsteps could not be heard. Inmates were only called by their numbers by guards, and an alternative panopticon was also in place, being able to look directly into all inmate corridors, though without the ability to observe each cell individually. This regime of silence and isolation was thought to allow inmates to reflect on their past criminal offenses and deliberately commence a process of self-transformation into a “righteous” individual, as Bentham had hoped. And yet, such methods proved to be psychological torture more than they were corrective. Subjecting inmates to total alienation from their human nature was mentally disturbing, with many developing serious illnesses and anti-social behavior. These often unintentionally led inmates into snapping within the prison, whether that was physical violence, screaming, or other reactions going against the silence regime. Yet, the usual response of the penal instrument was solitary confinement, which fuelled such mental disturbances and hence anti-social behavior even more.

It is thus no surprise or coincidence that recidivism remained high. An environment that pushes inmates’ mental trauma to its limits also strips them of any chance of re-integrating into society and thus makes crime the only familiarity they can cling to. The reformist penal institutions are overtly criminogenic; they fabricate offenders. Turning from one-time offenders (stealing bread, toys, etc.) to career criminals after going through the Separate Prison was nearly becoming the norm.

Parents and penal offspring

Unfortunately, these penal institutions of “correction” not only exist today, but they are the norm, Supermax correction facilities are the predecessors of colonial prisons like Port Arthur, and remain intact in their penal legitimacy, despite systematic evidence of the mental decline and recidivism they cause. This shows that in effect, the criminal justice system cares less about delivering meaningful punishment, and more about delivering traumatic punishment to those it desires to consider as offenders. Going back to Foucault’s thesis, the prison works because it fails. And if we seek to alter this parasitical penal system, the first place to look would be its deep, entangled roots.

References

- Cooper, R.A. (1981). “Jeremy Bentham, Elizabeth Fry, and English Prison Reform”, Journal of the History of Ideas, 42(4): 675–690.

- Foucault, M. (1979). ‘The body of the condemned’, in Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison, Vintage Books, 3–31.

- Rose, L.A. (1998). “Panoptical Intimacies”, Public Culture, 10(2): 285–311.

- “The History”. Portarthur.org.au, Available here