By Maria Papagiannopoulou,

The roots of Halloween can be traced back to the ancient Celtic celebration of Samhain (said as sow-in). The Celts, living around 2,000 years ago primarily in regions now known as Ireland, the UK, and northern France, marked their new year on November 1. This day signified the culmination of summer and harvest and ushered in the chilly, dark winter months; a time often linked with death. They believed that during this period, spirits roamed more freely, aiding druids or Celtic priests in forecasting future occurrences while also occasionally causing crop harm. For the Celts, these prophesies offered solace during the bleak winter, given their heavy reliance on nature’s whims. To commemorate Samhain, Druids lit grand sacred fires, where the community would convene to offer crops and animal sacrifices to the Celtic deities. By AD 43, the Romans had conquered most of the Celtic territories.

Over the 400-year span in which the Romans ruled Celtic territories, two Roman festivals merged with the ancient Irish celebration of Samhain. The first was Feralia, observed in late October by the Romans to commemorate the deceased. The second honored Pomona, the Roman deity of fruit and trees, symbolized by an apple. This association likely gave rise to the current Halloween tradition of apple bobbing. In A.D. 609, Pope Boniface IV consecrated the Roman Pantheon to all Christian martyrs, establishing All Martyrs Day in the Western Church. Pope Gregory III later expanded the festival from May 13 to November 1 to include all saints and martyrs. As Christianity permeated Celtic regions in the 9th century, it melded with and replaced age-old pagan traditions. In AD 1000, the church introduced All Souls’ Day on November 2, a day dedicated to the deceased. It’s widely accepted that the church intended to supplant the Celtic day of the dead with its own, similar observance.

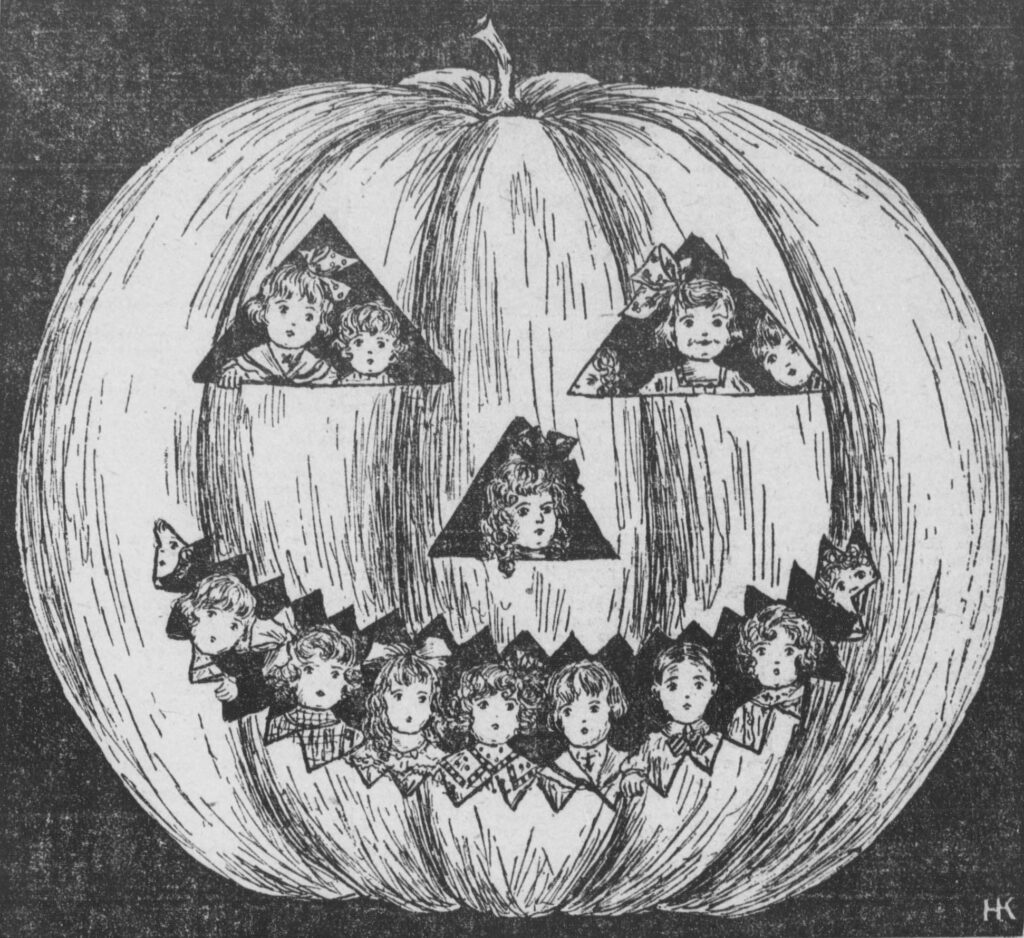

All Souls’ Day had traditions reminiscent of Samhain, including grand bonfires, processions, and costumes depicting saints, angels, and devils. The observance of All Saints’ Day, also known as All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from the Middle English “Alholowmesse” signifying All Saints’ Day), led to the eve before, coinciding with Samhain, being termed All-Hallows Eve and, over time, Halloween. Adopting European customs, Americans started dressing up and visiting homes requesting food or money, evolving into the contemporary “trick-or-treat” ritual. On Halloween, young women thought they could divine details about their future spouses through specific tricks using yarn, apple peels, or mirrors. By the late 19th century, a movement in the U.S. steered Halloween towards community gatherings and away from its eerie, mischievous origins. As the 20th century approached, Halloween celebrations predominantly became about parties for all ages, emphasizing seasonal games, foods, and costumes. Community figures and media outlets prompted parents to remove the scarier elements from Halloween festivities. Consequently, by the early 20th century, Halloween had largely been stripped of its superstitious and religious connotations.

In the North East of the UK, Halloween is a blend of traditional and contemporary celebrations. Children dress up in costumes and go trick-or-treating, visiting houses in their neighborhoods to collect sweets. Carving pumpkins into “jack-o’-lanterns” and displaying them outside homes is a popular activity. The region, rich in history, often capitalizes on its local folklore and ghost stories, offering haunted tours of ancient buildings and streets. Many community centers, schools, and local organizations host Halloween parties, complete with games and festive treats. Moreover, given the area’s historic backdrop, some castles and heritage sites host special Halloween-themed events or ghost walks, delving into the legends and mysteries of the North East. The celebration, while in line with broader UK customs, is enhanced by the region’s unique history and tales.

References