By Carmen Chang,

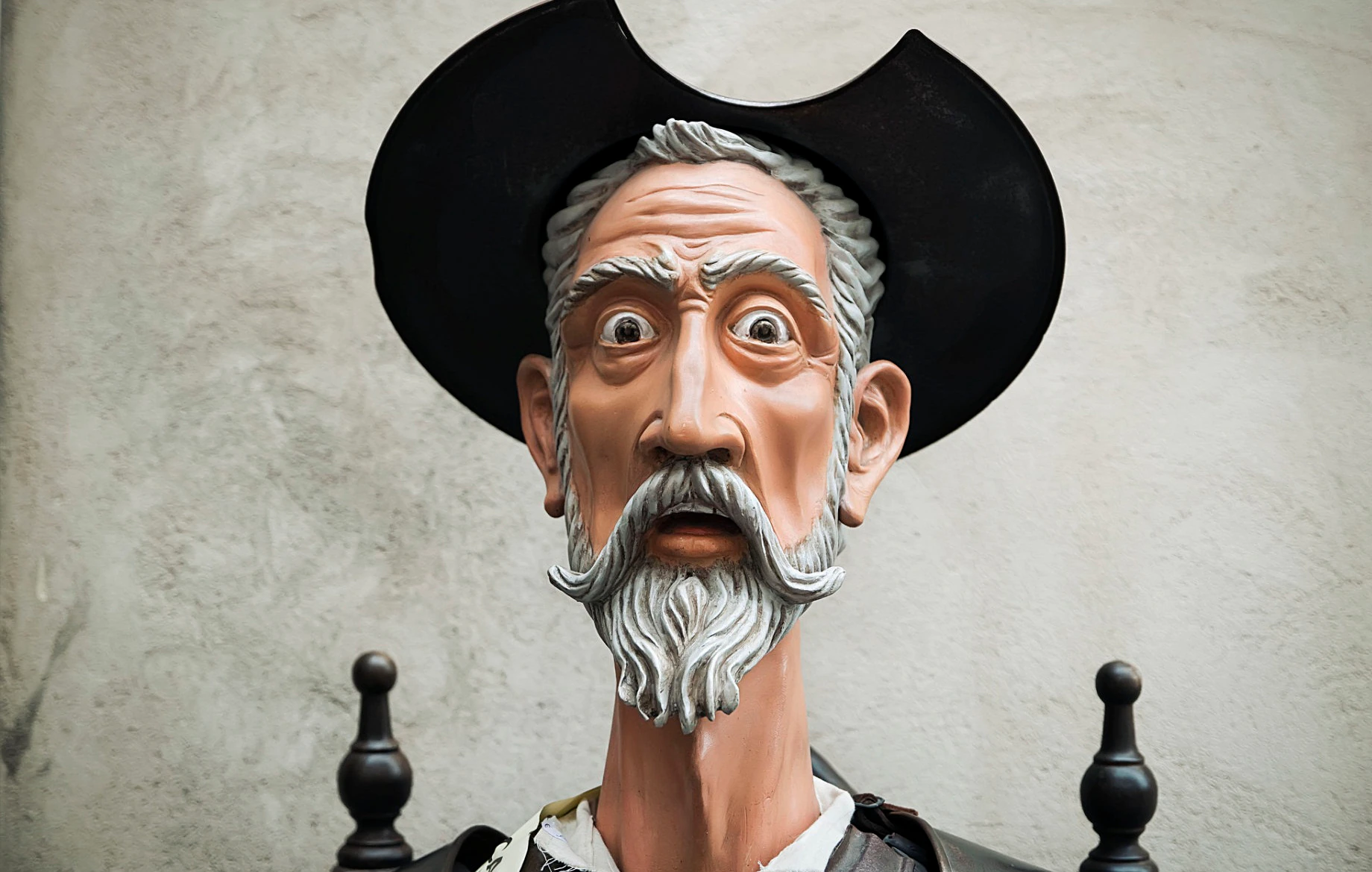

The real circumstance at the origin of this project on Don Quixote (1605), here it is: passionate for Hispanity and studying the seminar Myth and Utopia: Perspectives on the Quixotic Gift, which served as inspiration and then I planned to do the translation and illustration of the term «quixotic». Actually, «quixotry» is only available in Spanish Wikipedia, but in a rather simple and concise way. Moreover, the allusive illustrations of Don Quixote are also limited.

My first objective is to promote the dissemination and popularization of a term that must, must, and should have a great transcendence in society by the added value that the knowledge of the work and the character of «Don Quixote» represents by the universal culture and literature of all times. Apart from his educational, literary and linguistic contributions, this character also inspired several writers and artists. It is precisely for this reason that it seems relevant to me to choose and share certain illustrations for their contribution to artistic and cultural values.

I am concerned about the difficulties. On the one hand, the definitions given are of a limited nature in both Spanish and French compared to other words such as «Quixote» or «Don Quixote». Indeed, their definitions are too simple and not complete enough. On the other hand, it is obvious that the majority of illustrations are copyright and only some of them are free of rights. For this reason, I must be careful and cautious correctly citing and asking permission from artists or their foundations due to copyright infringements.

Moreover, Don Quixote had so much of a decisive role in all the changes they brought about at the end of the middle age, thus giving way to rebirth. It culminated with serious novels of chivalry, presenting an unusual character, truly human, allowing to know humanity, its errors, and its virtues. This work revolutionized literature and changed the way readers think.

Cervantes and his character are thus associated: as Don Quixote, he was honest, as he had the taste of wandering and travel, as he still loved to tell and wanted to fight against the forgetfulness of values. The vision of Cervantes (1605) could be summed up by the following quote: «For me Don Quixote was born alone. He knew how to work, and I write. He and I are one».

Quixotism

Quixotism is a condition or action of an idealistic man who acts in a disinterested way to defend causes he considers right, characteristic of the character of Don Quixote, hero of the novel of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote of the Channel.

Etymology

Origin, history, or word formation

This word is composed of the name “quixote” and the suffix “ism” which indicates attitude, conduct, behaviour, procedure or custom.

Definition

Who is, concept or meaning

Male noun. It is understood by quixotism the exaggeration, the extravagance or the rarity of the chivalrous feelings which is specific to the character of don Quixote. Pride, arrogance, forfeiture, endorsement, boasting, contempt, vanity, pride, boastfulness, imprudence, irascibility, which seems what it is not and the naivety proper to the Cervantes character.

Literal Background

For a long time, it was assumed that the character Don Quixote was inspired by a real character.

Possible sources of basic inspiration, if not exactly models, were perceived in several anecdotes and memoirs of the time, some allegedly real, on people with obsessions or disorders or who have reacted with extravagance to reading literary works.

Apart from the festive humour, the most important here is the iconographic aspect. The iconic and popular antecedents of the two Cervantes heroes may have contributed little or no to the subtleties of Romanesque characterization, but they may explain much of their powerful visual appeal. There is no couple of characters in Western literature that is recognizable in a more immediate and universal way, even for people who have not read the book. This effect is due not only to the qualities of Cervantes for the short and lit description, but also to its identification with a certain archetypal element. The carnival precedent also makes it possible to understand why the characters of Cervantes became known so quickly during festivals and processions around the world.

That said, it would be prudent not to give too much importance to these precedents, whether historical, literary or pictorial. Researchers, always looking for sources and affinities, tend to underestimate the imaginative originality of fiction writers. Regarding models drawn from reality, Cervantes could have argued, like Graham Greene, that «experience has taught me that I am given to base a secondary and momentary character on a real character. A real character is an obstacle to the power of imagination». The same can be said of the main literary «models».

Intention of the novel

In writing Quixote, Cervantes wanted to ridicule the cavalry books, which enjoyed enormous popularity at the time. “It is not another of my desires”, says the author in the last chapter, “that the most architectural and disparate stories of cavalry books are turned away with disgust”.

Don Quixote’s true intention is to be literally a cavalry romance hero, which means he’s trying to turn his life into a chivalrous romance. He even thinks that his actions are recorded in a book (he is right, but not the book he believes). It fails irretrievably because life cannot be treated that way. The result is not a true imitation of literature, but rather an accidental comic parody. The effort is even more absurd considering that the type of literature he chooses to imitate is not the narrative genre, but an extremely fabulous genre. The comical and ironic possibilities of this kind of parody were endless. Despite the romantic remoteness, some of the original situations are evident even to the modern reader.

Argument

The Manchego Hidalgo Alonso Quijano, called by his neighbours «the Good», went mad reading books of chivalry and resolved to become a knight errant, under the name of Don Quixote (Quixote) of La Mancha and embarked on the adventure to achieve his ideal: repair injustices, protect the weak, destroy evil and deserve his lady as a reward for his prowess, Dulcinea del Toboso (in reality, the mop Aldonza Lorenzo, idealised by him and which does not appear in the whole novel).

Don Quixote and Sancho

The main characters of the work, around which the others form the frame, are Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. The first is a madman, and his madness is the basis of the novel, which begins when it manifests and ends when the protagonist finds reason. This madness does not always offer the same characteristics. In the first part, Don Quixote disfigures the reality that is offered to him before his eyes by adapting it to the fantasies he read in the cavalry books. Thus, he sees a castle where there is only one sale, he distinguishes giants who are only mills, he contemplates the herds and imagines that they are armies, etc.

Sancho’s figure is of vital importance. On the one hand, it opens the way to dialogue. The conversations between Don Quixote and Sancho are one of the greatest attractions of the novel and allow us to situate ourselves in the way of thinking of Don Quixote. On the other hand, it is the pretext to oppose two completely different characters. Facing the idealism of Don Quixote, Sancho appears as a rough, greedy, and rustic being. He does not understand the extravagances of his master, and, in the first part, he is instructed to warn him that the wonders that his mind imagines are only normal manifestations of a daily and vulgar reality. However, it happens involuntarily to participate in the ideal and generous impulses of don Quixote, and, in this sense, one can speak of the progressive quixotization of Sancho.

Style

The prose of Quixote takes on a multitude of stylistic modalities that bring to the text a naturalness and fluidity absent in the Castilian novel of the seventeenth century. Detailed descriptions and narrative scenes reveal great ingenuity. The descriptions of disputes, disputes, tumults, and beatings succeed in conveying the impression of rapid movement masterfully, and they are examples of narrative dynamism that are difficult to imitate.

Importance of the Quixote

Already since the appearance of the first part, the success of Quixote was fulminant and many imitations soon appeared, the most famous of which was the apocryphal Quixote (1614) by Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. Initially considered as a humorous novel, we tried to understand the work more deeply from romanticism and, since then, we have seen all kinds of interpretations. Don Quixote is undoubtedly a madman, but this madness makes him a model of behaviour, because at all times he fights against the wind and the tide for his high ideals: love, justice and freedom. His influence on European literature was enormous and, to a large extent, it gave birth to the modern realist novel, especially by its influence on the British storytellers of the eighteenth century, with whom he began the great European novel.

Posterity

Quixote served as a reference text for many later works. Cervantes felt in the second part of his novel that it was in fact an answer to the first part and to the apocryphal hazelnut Quixote, that his text would require comments and that it would then provoke different and varied interpretations. Don Quixote says in the third chapter of the second part: “And so must be my story, which will need commentary to understand it” (Cervantes, II: 571), although the bachelor Samson Carrasco does not believe it. The past four centuries have shown that Cervantes was right: the ingenious hidalgo of the Channel and his travelling companion, the squire Sancho, have entered the mythological and archetypal field. His story has been read through history in a thousand ways. “Thus, as in a game of lights and reciprocal reflexes, many aspects of Quixote are discovered in countless novels from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries and vice versa” (Riley, 2004: 7). Among these novels is also the key text of the post-war Spanish of the twentieth century, Time of Silence by Luis Martîn-Santos.

REFERENCES

- CADAVIECO GOMEZ Guillermo, Don Quixote and the Philosophy of the Hero, Acrópolis Review, Editorial No. 304, 2016. Available here

- CANAVAGGIO Jean, Cervantes. Nouvelle édition revue et augmenté [1e éd. 1986] Paris, Libraire Arthème Fayard, 1997. 382 p.

- CHANG Carmen, Don-quichottisme, Wikipedia, 2019.Available here

- DORÉ Gustave, Illustration on Don Quixote, 1906. Available here

- SARMIENTO SILVA Sergio, Hispanic Encyclopedia Macropedia Volume 12, Barcelona, Enciclopedia Britannica Publishers Inc., 1995-1996, 408 pp.