By Eirini Tassi,

Referendums are an integral element of healthy democracies, allowing citizens to directly decide on vital socio-economic, civic, and political issues within their polities. Many significant political events occurred through referendums, from Brexit and the 2016 Dutch-Ukraine referendum to the constitutional transition of Spain after the fall of Franco. Australia, who has a referendum scheduled for October 2023, has the chance of becoming part of that list: citizens will be called to choose whether the country’s First Peoples, meaning the native populations that existed in that land before European settlers, should receive constitutional protection. Hence, the referendum itself does not merely bring vital political outcomes for the different parliamentary parties involved, but arguably determines First People’s legal visibility {constitutional recognition}, and in effect, Australia’s ethnocultural future.

Colonialism 101: Res nullius and the great heist

“First Nation Australians” refers to the indigenous populations that inhabited Australian lands, including Tasmania, before European colonization. These include a wide range of ethnic groups of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who lived in hunter-gatherer, territorially distinct societies within these lands. There, cultural plurality appeared to be the zeitgeist of their historical trajectory: they were engaged in distinct cultural and spiritual activities tied to the soil they inhabited, while they also developed their own trade environments.

It was colonization that put a harsh end to this symbiosis in the 18th century. When British settlers arrived in Australia in 1788, they conquered the land and put it under the governance of the British Empire, despite evidence that several indigenous tribes already occupied these areas. They acted based on the principle of res nullius, which at the time of European colonization meant that a country can legitimately occupy and claim ownership of a land that is an “unsettled and uncultivated land of nomads”. In short, this meant that as long as a land was not used for agrarian purposes and was not owned by a nation-state that European powers perceived as legitimate, such actors were free to colonise it. This in turn implied that Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders, who were organized in semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer structures, were seen as illegitimate inhabitants of Australian soil, and hence, targets of holistic conquest and enslavement by the British. Of the estimated 300.000-1.000.000 indigenous peoples inhabiting Australia prior to colonization, many died from diseases the British brought from Europe, like smallpox. Not only did native groups have no antibodies against them, but they were also unable to receive any medical treatment because their conquerors refused to perceive them as humans (I would say “fellow” humans, but it’d be quite an oxymoron calling colonisers that). Many were also subject to brutal torture, being poisoned with strychnine, and even being burned alive. Those who escaped the diseases and genocide did not meet a better fate. Most were forced to work in the pearling and then cattle and pastoral industries, under harsh labour conditions and continuous (sexual) abuse by employers. They were seen as nothing more than tradeable commodities, to the extent that supervisors had no problem taking their lives when they stood up to their oppression.

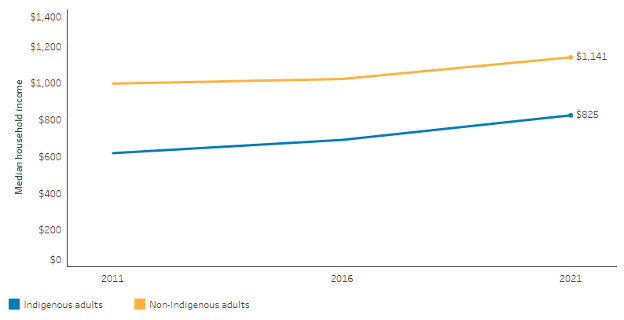

Looking at Australia today, many things concerning Indigenous peoples have changed for the better, but many have also stayed the same, the most important being that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are not recognised by the Australian constitution. While the outcome of the 1967 referendum, in a detrimental step forward, gave them the right to vote in state and federal elections, Indigenous Australians are still largely institutionally disadvantaged compared to European-descended Australians. The indigenous health campaign, for example, points out the persistent inequality in health and life expectancy between the two parties, much of which results from asymmetric institutional access to health services and lesser health infrastructure in indigenous communities. Furthermore, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports that as of 2021, the gap in median gross weekly equivalised household income between indigenous and non-indigenous adults is $316, which directly affects their access to health services, surgeries, and immediate care. Such institutional disparities, though slightly diminished, have been persistent for many decades, essentially making Indigenous Australians second-class citizens in their own land.

Here is where the referendum enters the scene. In 2022, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese proposed an amendment to the Australian constitution with a Bill that gives a more deterministic parliamentary voice to Indigenous Australians, by establishing an advisory committee of Indigenous people to the government. This is vital, as it will allow Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders to actively inspect whether proposed policies are in the interests of their communities, and propose modifications where necessary. In particular, according to ABC News Australia, this will be done by adding the following sentences to the constitution:

- In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

There shall be body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice - The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice including its composition, functions, powers, and procedures.

This was passed on both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and in October, Australian citizens are called to decide whether the constitutional alteration should be executed or not. In particular, the referendum ballot includes the following:

To alter the constitution to recognise the first peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Trait Islander voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?

Citizens must respond with either “yes” or “no”.

As this brief historical and political report shows, Australia is one of many former European colonies whose inequalities between European-descended and indigenous populations have trickled down to the modern socio-political climate. By recognising the need to address this chronic disparity, Australia is taking a step that other countries, like the United States, are largely hesitant to take vis-à-vis their own native populations. One thing to hope for now, is that this following October, the unbridgeable, whether that is wealth, health services, or social treatment, will finally become bridgeable.

References

- Understanding Australian Aboriginal Culture. goliveitblog.com. Available here

- The 2023 referendum. aec.gov.au. Available here