By Eirini Tassi,

The US foreign (trade) policy arena is undeniably heavily divided; whether it is the continuous clashes of interests between the financial and manufacturing industries or the rollercoaster of tariffs, with taxes on imports skyrocketing with Trump and then curving with the Biden administration. Many attribute this contestation to China’s alarming economic growth, to the 2008 financial crisis, or other significant recent trends that compel US industry actors to choose sides and firmly defend their individual interests. Yet, a quick glimpse into the past shows that this is nothing new.

Hegemon? Hard pass

World War I was the destabilizing zeitgeist of the early 20th century. It could be argued that it nearly pushed us back into a state of nature. Countless deaths, contested territories, and torn economies with nonexistent autarky. European nations (amongst others) of both the Entente and Central Powers, who were at the geopolitical locus of the conflict, were trying to pick up any pieces of themselves that could still be picked. In that respect, the US came out of the war in a much more dominant and capable position. Despite formally maintaining its neutrality until 1917, the North American nation rigorously supplied weaponry and other war goods to the Entente throughout the 1914-1918 period, which ultimately allowed the US economy to overcome its recession, and transform from a debtor in international capital markets, to a strong and trustworthy lender. In other words; in just 10 years, New York City became the new London. British hegemony was already experiencing decline since the early 1900s, but it was ultimately WWI that led to its holistic underestimation, and paved the way for the United States to take over. And it really wouldn’t be difficult: they were not geopolitically and territorially affected by the war, and their export-oriented, lender economy was internationally uncontested. Yet, in a pattern that would repeat itself numerous times over the decades, the country opted to maintain a more isolationist stance, rejecting its potential for global hegemonic governance. This was his answer to a long-contested question across IR scholarship: why did the United States reject the role of global hegemon after WWI despite having the uncontested capacity to be one?

In his 1988 essay “Sectoral conflict and foreign economic policy”, Jeff Frieden provided a convincing answer. He characterized the US foreign policymaking from 1914 to 1940 as a continuous situation where “internationalist financiers and their allies in the State Department and the Federal Reserve faced the opposition of nationalist forces in Congress and other segments of the executive”. In short: the answer lies in domestic polarization. In particular, what impeded the US from becoming globally oriented and ultimately take a post-WWI hegemonic role, was the division of domestic foreign-policy actors in two warring positions: the internationalists, who supported an outward oriented US economy, and the nationalists, who preferred an inward, protectionist one. Frieden supports his claim with historical empirical arguments which demonstrate how these two interest blocs rose against each other, and how the nationalist bloc succeeded in keeping the US economy largely isolated until the late 1930s.

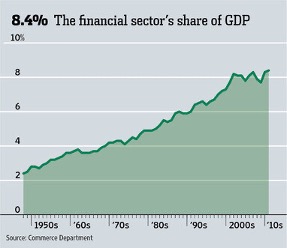

Domestic polarization occurred because global-trade benefits were unevenly distributed amongst US industries (Frieden 1988: 60-61). New York became the world’s financial capital during WWI, with bankers and financial firms becoming leading foreign-direct investors (FDI) and lenders of US capital, especially towards war-torn European powers. Therefore, the finance industries rigidly advocated for an internationalist, free-trade US economy, because this would strengthen their capital returns from foreign borrowers and from FDI. foreign activities (ibid.). On the contrary, most other US industries, especially those producing manufactured goods, were more domestically-oriented; they had limited foreign assets and investment, and hence limited competitiveness compared to foreign firms. Thus, they advocated for a tariff-based US economy which would protect their output against attractive imports (ibid.). Interests from international trade were hence all acquired by financial sectors, disadvantaging most other industries (ibid.). This fueled polarization between the two groups, and urged nationalists to continuously oppose propositions for US foreign economic expansion. The state was thus mostly unable to implement a pragmatic globalist foreign policy.

This, was reinforced by the fact that the US state apparatus was itself divided between internationalists and isolationists (Frieden 1988: 75). The Federal Reserve and State Department were predominantly internationalists, while the Congress and executive had mostly isolationist advocates (ibid.). Both groups thus continuously clashed, with neither having enough majority to completely suspend the powers of the other, but with nationalists having sufficient legislative power to override the Federal Reserve to some extent (ibid.). When bankers, for example, pushed for new US-loans towards European powers to facilitate their reconstruction, Congress vetoed it (Frieden 1988: 82). Therefore, it is the inherent architecture of uneven free-trade interests that fueled polarization, then entered the political arena of US foreign policymaking, and ultimately made it idle and nationalist-led until the 1930s. Frieden’s overall dissection of such economic interests shows his emphasis on domestic, material foundations as determinants of US-foreign policymaking (idem: 90).

These determinants appear to persist.”This polarized relationship between protectionist and free-trade advocates can still be seen to a smaller, but evident extent in the ongoing US-China trade war. The United States’ neoliberal, global economic agenda is guided by the infamous “Wolves of Wallstreet”: financial-advisory firms like BlackRock and Fidelity, and investment banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. As with the early 1900s, the Federal Reserve is dominated by such figures, with its chair and board committee consisting of investment bankers like Jerome Powell (Federal Reserve 2022). These continuously lend USD-capital to foreign states and perform FDI. For China, such investment is currently estimated at around 118.19 billion USD. At the same time however, US producers of raw commodities continuously advocate against this financial openness, arguing that cheap Chinese imports of steel and aluminum outcompete them in domestic markets (Lincicome 2021). US administrations have thus simultaneously sought to protect such firms through tariffs on various Chinese goods, an act which made executive and Republican legislative members to continuously clash with the financial industry. This polarization, that Frieden previously analysed, was heightened during Trump’s governance, as he implemented very rigid protectionism, like steel tariffs and import quotas for China, aiming to strengthen domestic autarky on raw commodities.

Whether this polarisation will be ever put to ease is a good question. Whether it is democratically legitimate for financial industries to push their interests on top of a much wider scale of other US industries is an even better question. And whether the US foreign policy is following a historical path dependence, is probably the million-dollar question.

References

-

Federal Reserve. (2022). “Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System”, federalreserve.gov. Available here

-

Frieden, J. (1988). “Sectoral conflict and foreign economic policy, 1914–1940”, International Organization, 42:1, 59-90.

-

Lincicome, S. (2021). “How American Steel Protectionism Harms American Manufacturers in One Simple Chart”, cato.org. Available here

-

“Direct investment position of the United States in China from 2000 to 2021”. statista.com. Available here

-

“The Economics of World War I”. nber.org. Available here