By Evi Tsakali,

Émile Durkheim illustrated incrimination as a means to establish domination; since laws replace customs and traditions, the incrimination of action is not the instinctive reaction of society as a whole anymore, but of an authority establishing its domination. On the other hand, we have the French jurist Jean Carbonnier, who, in his Theories of stigmatization, referred to the criminal law of the tragic (“le droit penal du tragique”), meaning that we have a tendency to make any situation regarding criminal, behavior too dramatic for the sake of moving the public; but as he underlines “too much spectacle makes people blind” (“trop de spectacle rendrait aveugle”). He also calls criminal law the law of non-law (“le droit du non-droit”), since – despite living in the era of the Rule of Law – many people have the impression of being able to solve their differences themselves. Because of a primitive impulse to seek revenge and vengeance, victims are transformed into agents responsible for the suppression of the crime committed. Nevertheless, even if it is legitimate, passion can be questionable. In that sense, this article will combine a descriptive presentation of the different crime prevention models.

Before examining the different policies, we need to acknowledge the complexity of the notion of crime prevention; for some, crime prevention may mean better education, for others it could mean a court decision or the police making an arrest, or even just a number of security measures implemented on a community or national level. What can be stated with certainty is that the goal of crime prevention is to prevent the commission of future criminal acts; what distinguishes it from crime control is that it does not necessarily involve the formal judicial or police system. Regardless of whether the formal judicial or police system is the principal policy maker and/or implementor, a typology of prevention strategies was proposed by Tonry and Farrington in 1995, distinguishing developmental prevention, community prevention, situational prevention, and criminal justice prevention.

Developmental Prevention

The developmental prevention model aims at the heart of the problem; to combat crime from its roots. It focuses on ameliorating the living conditions for children so they will not pursue a life of crime by emphasizing the triptych: early prevention-reduction of risk factors-fostering protective factors.

The risk factors can be a product of the individual itself and by that, Tonry and Farrington imply personality traits such as temperament, impulsiveness, and lack of empathy or intelligence; indicators of potential future criminality. The developmental crime model responds with programs tailored for the intellectual enrichment of preschool children as well as special training to develop children’s EQ (emotional intelligence).

However, the family’s influence is not to be neglected. Children that have grown up in disrupted households with poor parental supervision, incidents of domestic violence, or even criminal, or, at least, anti-social parents have higher chances of pursuing a life of crime themselves. In that sense, the developmental prevention model proposes home visiting programs to assess the households presenting such circumstances, in addition to the establishment of “parenting schools” or related action plans.

Eventually, there are also delinquency-encouraging factors that constitute the fruit of the general environment in which a child grows up. Such conditions include – but are not limited to – having a low socio-economic status, living in deprived regions, and/or attending schools that present high juvenile delinquency rates. For the proponents of the developmental prevention model, these factors could be mitigated by school interventions and community-based discipline management.

Regarding the efficiency of this model, according to Professor Ross Homel, an expert on developmental criminology, “doing something about crime early, preferably before the damage is too hard to repair, strikes most people as a logical approach to crime prevention. The twin challenges, of course, are to identify exactly what it is in individuals, families, schools and communities that increase the odds of involvement in crime and then do something useful about the identified conditions as early as possible” (Homel and Thomsen, 2017, pg 57). Thus, the professor both illustrates the benefits and highlights the struggles of implementing this method.

Community Prevention

The model that this section is dealing with, Community prevention, considers a community an ideal space where crime can be combatted, with the prerequisite that community bonds are strengthened so that criminal activity and fear of crime are reduced. The ambition to promote such as model occurred directly from police data which indicated that most crimes are committed within the area where the victims or the perpetrators live, especially in large urban centers.

Deducing from the aforementioned that a sort of informal control by local communities should be implemented, the community crime prevention model has been implemented or tested firstly in the USA, and later in the UK, the Scandinavian countries, and France during the second half of the previous century. In general, the implementation of the model in those cases consisted of establishing local Crime Prevention Councils, whose competencies included local policy-making and research on criminological affairs, as well as the promotion of citizens’ initiatives regarding their safety and community surveillance.

From the scope of resources, the community prevention model can be proven very financially beneficial to the states, whose crime prevention policies and competencies are now derived from local communities. However, this significant shifting of power to a local level could potentially cause authority conflicts and instigate controversies on state sovereignty in criminal matters.

Situational Prevention

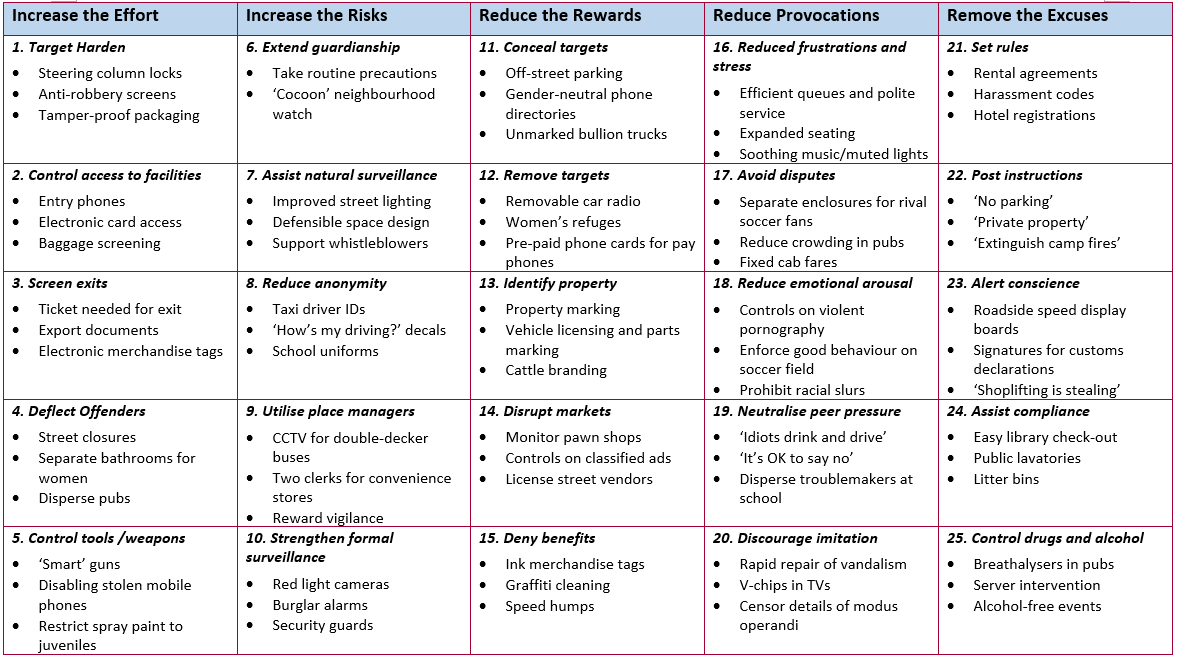

Situational prevention – as its name implies – consists of strategies that form circumstances in a particular way so that committing any crime would be rather risky or even impossible. If we were to summarize this model’s main principles, that would result in the following sequence: increase difficulties, increase risks, reduce the gain, don’t provoke, and limit excuses.

As a matter of fact, we all – at an individual or community level – implement this model to a certain extent without being aware of it. Practices such as installing an alarm, hiring a security guard, parking an expensive car in a garage instead of in plain view, watching out for personal belongings, controlling drugs, alcohol, and guns, identification procedures, and visible posters or banners with the rules of a public space; they are all situational prevention strategies.

Simply put, situational prevention encompasses basic gestures and security measures we are accustomed to for our own safety. Consequently, it shifts the emphasis to individual responsibility when it comes to crime eradication.

Criminal Justice Prevention

Finally, the criminal justice prevention model entails law enforcement as operated by the criminal justice system. Therefore, its principal actors are the police, courts, and prisons. In the first place, this model’s approach seems to be rather repressive, but these three actors can also function in a preventative manner, through a diversity of actions. More specifically, the police forces, courts, and prisons achieve a fundamental criminological concept; that of deterrence.

The courts’ deterrence factor hides in their own decisions; the idea is that when a person is sentenced by a court, they well will probably be deterred from committing crimes in the future. Police forces seek crime deterrence via their very presence and involvement in communities. The logic behind it is that – with effective neighborhood policing – potential perpetrators will be discouraged from committing unlawful actions. Last but not least, in this theoretical structure, prison is considered the guarantor of rehabilitation, as a means to prevent re-offending.

Some conclusions…

Striving to achieve crime prevention, the judicial system, regardless of how solid it may be, ought not to stand alone. Factors such as individual responsibility or the role of communities are not to be neglected when it comes to mitigating criminal behavior. Furthermore, a reinforced educational system combined with strengthening the institution of family is more necessary than ever, since it will pave the way for young people to develop social and political skills and equip them with emotional intelligence to confront the obstacles that life may pose and not pursue a life of crime.

Very often, some crimes may seem outrageous, so much so that they might tempt people to take the situation into their own hands. However, the relatively neutral stance, especially of the student community, on the matter of vigilantism reveals how as citizens we may want to shout, but we have to be careful, for too much noise makes one deaf; and we would not want to deafen ourselves back to a worse state of criminality.

References

- Λαμπροπούλου, Έφη. “Μη Κυβερνητικοί Μέτοχοι Στην Πρόληψη Και Τον Έλεγχο Του Εγκλήματος: Ρητορεία Και Εφαρμογή Του Κοινοτισμού.” Πάντειο Πανεπιστήμιο Κοινωνικών και Πολιτικών Επιστημών.

-

“Detailed Explanation of Tonry and Farrington’s Typology.” The Doha Declaration: Promoting a Culture of Lawfulness, unodc.org. Available here

-

Welsh, Brandon C., and David P. Farrington. “Evidence-Based Crime Policy.” The Oxford Handbook of Crime and Criminal Justice, Sept. 2011