By Eirini Tassi,

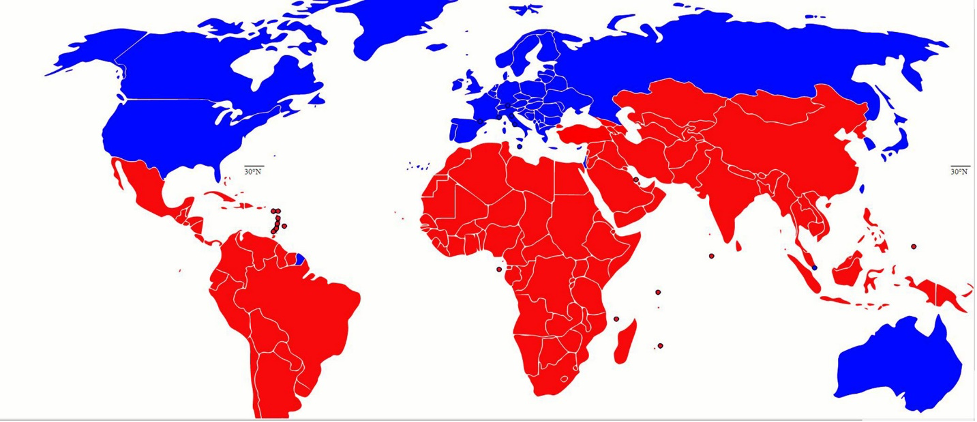

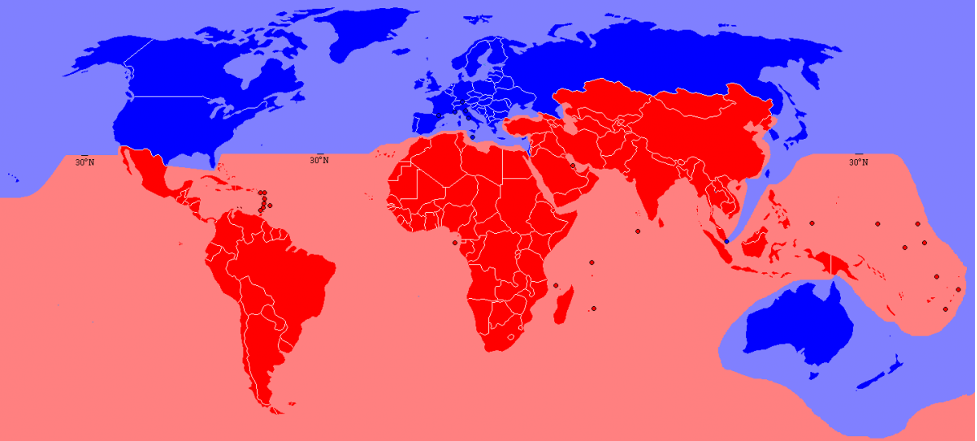

“Studying only the center, does not reveal to you the margins; but studying from the margins can inform you of the margins, the center, and their relationality; that is, the larger constellation of political activity” (Shilliam 2021: 17). This is what Robbie Shilliam stated in his 2021 book Decolonising Politics. His claim is sharply clear: conventional political science is Eurocentric (ibid.). It prioritizes Western (center, as he calls it) at the expense of non-Western political theorists (margins), with texts being unilaterally interpreted from the worldviews of the former scholars (ibid.). Therefore, we must de-peripheralize “the margins” and give all political actors equal agency when analyzing theories and historical concepts (ibid.). He hence proposes three steps that one can use to decolonize political texts: recontextualization, reconceptualization, and reimagination (ibid.).

Shilliam defines recontextualization as interpreting a political notion in the socio-political, historical, and colonial specifications in which it was written, instead of analyzing it based on modern contemporary politics (Shilliam 2021: 17). This can allow one to accurately reflect the intentions behind a political formulation. He illustrates that through the example of Aristotle: the way he perceives the polis cannot be compared with the modern idea of a polity, but must be interpreted hand-in-hand with the Greek settler-colonial geopolitics under which he lives, where imperial Athens is under threat from imperial Macedonia and Persia (ibid.).

This is where reconceptualization takes place, a process that Shilliam defines as the production of new conceptual definitions adapted to their socio-historic context. In the case of Aristotle, the analysis of the imperial powerplay between Athens, Macedonia, and Persia reveals that his conceptualization of the polis derives from his desire to warn Athenian citizens of the dangers of producing an imperial Athenian empire: this would make Athens vulnerable to foreign conquerors and its citizens vulnerable to losing their citizenship status, and in turn, their ability to participate in the political commons and reach eudaimonia. This refined conceptualization is crucial to the decolonization process, as it demonstrates that labels like citizen or slave are not inherently attributed to specific tribal groups like Athenians, as colonial logic would assume, but can change according to what imperial power dominates over another. If Athens got conquered by Persia, Athenian citizens would be reduced to slaves. Therefore, going back to the quote I introduced, this implies that the “center and the margins” are always relational.

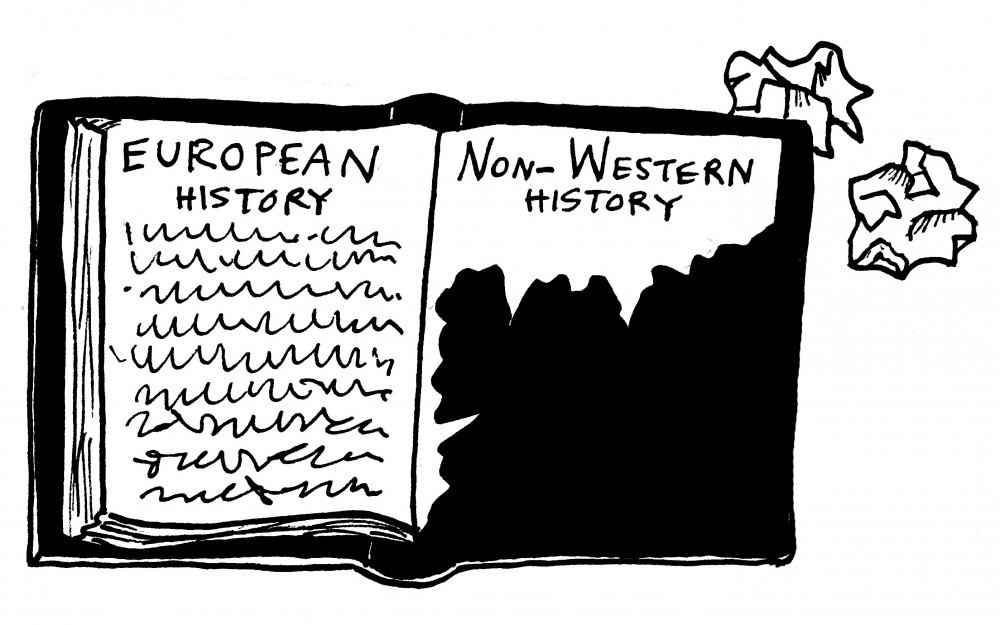

This brings us to the final step towards decolonization: re-imagining. Shilliam makes one thing clear: political science is currently written by winners. It is written by imperial European actors, these so-called “canons” that dominate(d) the international system, and it is hence their conceptualizations and theories that prevail in international relations. Therefore, he argues that we should bring forth non-Western theories and theorists that have remained peripheral, as this would allow us to interpret a political text holistically, looking at both the “canon” and “margin” sides.

He also states that even if there is no political discourse expressing the side of marginal actors, our task is to imagine what their position would be, based on our previous recontextualization and reconceptualization. For example, Aristotle, who is seen as a canon by political academia, argues in favor of natural slavery, though we never hear from the Greek anti-slavery movement: we must thus attribute such actors agency and reimagine what enslaved individuals would perceive of their oppression and liberation (ibid.). Shilliam thus overall approaches decolonization in ideational terms; he de-peripheralizes non-Western voices by scrutinizing the norms, customs, and cultures under which them and “canon” theorists produce their texts.

This decolonization effort parallels Zeynep Çapan’s paper “Decolonising International Relations?”. Capan also identifies the asymmetrical Eurocentric domination of political science and wishes to de-peripheralize it by uplifting non-Western scholars (Çapan 2017: 8 and Shilliam 2021: 17-18). Nevertheless, her approach is more radical: she does not solely suggest bringing actors from the “margins” to the “core”, but abolishes that binary system altogether, as it is a mere Western construction to dominate over non-Western actors (ibid). Shilliam’s three-step process remains within that core-periphery duality. Concomitantly, however, they both appear to view decolonization in ideational terms: Shilliam references the reconstruction of political-science concepts in terms of their politico-historical specifications, and Capan, moving it a step further, advocates for the reconstruction of the normative Western-nonwestern divide, to attribute all actors equal agency in political academia (ibid.).

References

-

Capan, Z.G. (2017). “Decolonising international relations?”, Third World Quarterly, 38(1), 1-15.

-

Shilliam, R. (2021). “Decolonizing politics: An introduction”. John Wiley & Sons. Chapter 1: Introduction.