By Erika Koutroumpa,

The Earth, the planet that we all call our home, is a blue and green dot on the map, that is the galaxy. In the past few years, the efforts to protect its inhabitants of all kinds, whether flora or fauna, of the land or the sea, have intensified. Earlier last month, the member-states of the United Nations, after an intense negotiation process, finally managed to compromise with each other and create the UN High Seas treaty — an idea that has been in the making for the last 2 decades.

Ocean ecosystems produce half the oxygen we breathe, represent 95% of the planet’s biosphere and soak up carbon dioxide, as the world’s largest carbon sink.

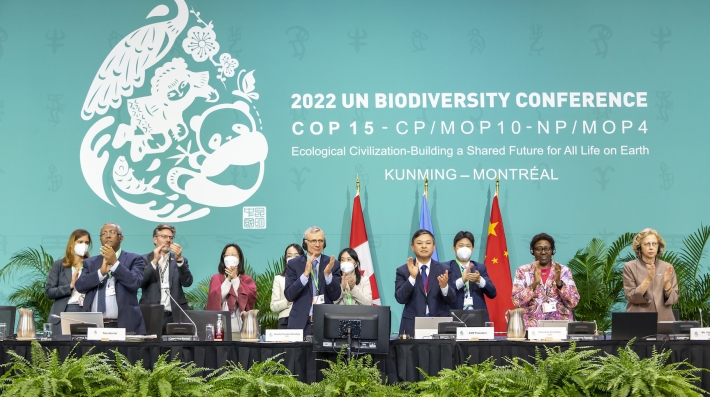

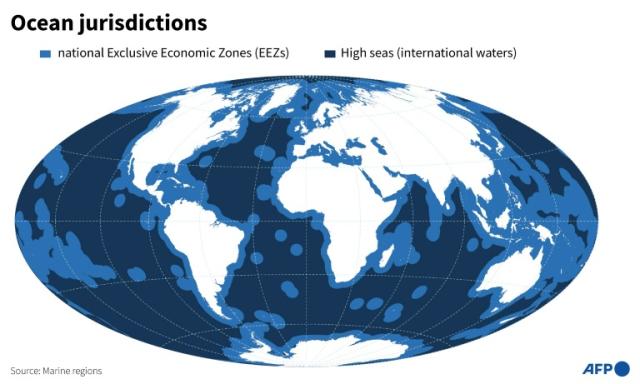

How does this treaty affect the current state of ocean protection? Currently, only 1/3 of the ocean is protected from exploitative and or polluting activities via national laws. The rest of the 2/3, which according to the treaty are considered the sea territories beyond the Exclusive Economic Zones of a State (200 nautical miles beyond a nation’s territorial area), is a first-come, first-served domain. The measures of the treaty aim to prevent these parts from pollution, overfishing, and marine life habitat destruction. Also referred to as the Paris Agreement for the Ocean, this agreement has been under discussion for several years but things kicked off with the UN Biodiversity Conference, COP15 in Montreal, Canada, where a landmark agreement to protect 30 percent of the planet’s lands, coastal areas, and inland waters by the end of the decade was established.

The treaty covers a wide range of areas necessary for more robust protection of marine biodiversity, besides just establishing the need for restoring ecosystem integrity. Member states can now vote to declare new marine protected areas, and countries must channel a portion of the profits from marine projects into a global fund for high sea protection, the details of which are still in progress. Furthermore, more responsibilities have been attributed to companies, thanks to a polluter pays principle, where those that cause pollution are responsible for its reduction, as well as through the introduction of mandatory environmental impact assessments before large maritime projects are commenced. The clauses do not stop there — they also cover the conduct of research. Scientists are now obliged to obtain informed consent from indigenous people before obtaining traditional knowledge associated with marine genetic resources. Lastly, there are provisions for the promotion of international cooperation in marine scientific research and the development of relatively new technology. This is highly important since there is a guarantee that signatories share profits from future commercialized products derived from the high seas.

So far, the treaty has been met with a warm reception, but this does not mean that does not have its downsides. It has been criticized by commentators for lacking specific provisions, although this could be a sign of constructive ambiguity, allowing for more creative freedom when designing plans of action by just functioning as a guide. Furthermore, it does not overrule existing regulations that unfairly benefit existing high seas activities, such as China’s plans of a shipping route through the Central Arctic Ocean and the search for metals in the Pacific that are said to be used for the batteries that will be needed to operate more eco-friendly devices. Furthermore, another loophole that has been pointed out is that existing fishing areas cannot be declared as protected areas, even if they should be considered as such. As a result, the issue of overexploitation of the seas for fishing, which was one of the focal points to be covered by this convention, cannot be covered effectively.

Finally, the countries have agreed that existing bodies already responsible for regulating activities such as fisheries, shipping, and deep-sea mining could continue to do so without having to carry out environmental impact assessments that have now been made mandatory for newer maritime endeavors.

To conclude, the new UN High Seas Treaty hopefully is the first step in the right direction for the protection of our planet’s oceans. Currently, only 1% of international waters is protected by law, but with the implementation of this agreement, the horizon of activity in the high seas is bound to shift significantly. Despite its possible shortcomings, the treaty provides a framework for the future course of action of researchers, companies, and Member States alike. Showing the potential of this initiative, the European Union pledged €40m ($42m) to enable the ratification of the treaty and its early implementation. However, it is important to remember that actions speak louder than words, and for our planet to truly be saved everyone ought to respect the rules set in place.

References

-

“Why the High Seas Treaty is a breakthrough for the ocean and the planet”, Gemma Parkes. climatechampions.unfccc.int. Available here

-

“The UN high seas treaty is a landmark- but science needs to fill the gaps”, Nature 615, 373-374 (2023)

-

“What to know about the new UN high seas treaty- and the nect steps for the accord, Juliana Kim, Rachel Treisman, 7 March 2023. npr.org. Available here

-

“Protecting ‘two-thirds of the world’s oceans’: What the UN High Seas Treaty draft agreement says”, Rishika Singh. indianexpress.com. Available here

-

“The Inside Story of the U.N. High Seas Treaty”, Jeffrey Marlow, 9 March 2023. newyorker.com. Available here

-

“High seas treaty: historic deal to protect international waters finally reached at UN”, Karen McVeigh, 5 March 2022. theguardian.com. Available here