By Maria Koulourioti,

Sometimes, loving someone is like loving war. However, is it classified as a feeling of deep affection and understanding or a substitution of one’s manner to overcome their trauma? In particular, to ennoble a relationship and romanticize to the extent of deceiving the public eye, is exceptionally usual between celebrities, artists, philosophers, and even politicians and monarchs. How does history treat these couples’ connections as a unique bond, an ideal association instead of a traumatic and unhealthy experience? Perhaps people always tend to believe what benefits their own situation, keep the positive traits of an attachment, and dignify it as “passionate”, rather than “obsessive”.

Starting off with a much more prestigious yet controversial monarch in the 16th century (1542-1585), Mary Queen of Scots who was just six days old when she became queen of Scotland and is often remembered for her three doomed marriages. Turning our attention to her explosive romance with her first cousin Henry Stuart (Lord Darnley) in 1565, their engagement was not only made because of his good looks but also because of his own claim to the English throne, thus the boost of Mary’s attempts to be officially named as her cousin Queen Elizabeth’s heir in England. However, hungry and jealous of her power, a harsh and haughty man, Darnley desired to be crowned King of Scotland and Mary’s equal co-ruler which infuriated both the monarch and the Scottish nobility.

The couple immediately separated and Darnley, furious that he was not being granted the authority he needed, decided to take matters into his own hands. In front of Mary, who was carrying his child, Darnley went into the queen’s private dining table in 1566 with his followers and stabbed her secretary and confidante, David Rizzo, to death. A little over a year later, there was an explosion at the Kirk O’Field residence, and Darnley’s body was discovered in the orchard without any signs that the explosion had claimed his life. It was shortly determined that he had been killed and many people thought Mary had given the order, ending a two-year relationship of power imbalance, blood, and mistrust.

The author’s personal favorite is the torrid love of Napoleon and Joséphine’s romance which is frequently praised for being passionate and romantic, but in truth, it was also turbulent and fierce. In 1795, they first connected at a social gathering hosted by Napoleon’s tutor and Joséphine’s lover, Paul Barras. Joséphine, who was six years older than Napoleon, captured Napoleon’s attention right away. They later were married in a civil ceremony in Paris. Later, Napoleon embarked on his first battle in Italy but not before sending his wife a number of fervent and lovesick letters, many of which she regularly failed to respond to while engaging in extramarital relationships and accruing debts at home. Napoleon furiously wrote to her after learning of her alleged infidelity: “I don’t love you; on the contrary, I detest you”. he started his own affair.

The couple’s main problem ultimately was Napoleon’s decision to divorce Joséphine in November 1809 because she was unable to bear him an heir. When she learned of this, she collapsed to the ground. Napoleon still had feelings for Joséphine even after their romance ended, and he made sure she had enough money to live on for the rest of her life. Napoleon reportedly spent two days alone when she passed away in 1814, and it is stated that he muttered, “France, the army, head of the army… Joséphine,” as he lay dying.

Another famous couple carved in art history’s thick canvases is the much controversial relationship of when two opposites attract, Frida Kahlo and Diego Riviera. It would be only an understatement to suggest that two of the best painters in Mexico and the whole 20th century had a difficult relationship. When Kahlo was 15 and Rivera was 36, they only had a brief encounter. Three years later, Kahlo was gravely hurt in a bus accident, which would cause her lifelong misery. She started drawing to pass the time while she was recovering. After rejoining the Mexican Communist Party in 1928, Kahlo met with Rivera; she showed him her artwork and he recognized her skill. They fell in love right away and got married in 1929 and Kahlo’s parents referred to them as “the Elephant and the Dove” because of their physical contrasts.

The artists really cared for one another but were disloyal to one another, which caused countless heated arguments. However, it was Rivera’s romance with his sister-in-law that profoundly affected Kahlo, and the pair split in 1939 before getting remarried a year later. Their artistic collaborations, notably Kahlo’s moving self–portraits and her thoughtful letters to Rivera reveal their bond. They stayed wed up until Kahlo’s tragically early death in 1954, which devastated Rivera. In the biographical movie “Frida” starring Salma Hayek, we can sense Frida’s power of forgiveness, being there for all the people she loved, even if they betrayed her trust.

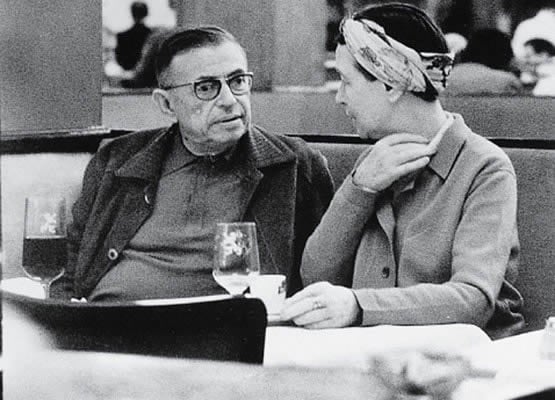

Sometimes, love affairs can be toxic not only between the couple but to others as well. The mother of contemporary feminism and the father of existentialism collaborated on ideas for fifty years in a relationship that defied social norms; they never lived together but shared each other’s work and lives. At the Sorbonne in 1929, De Beauvoir and Sartre were rivals and classmates while they pursued the renowned graduate degree known as the aggregate in philosophy. De Beauvoir had better grades than Sartre but at age 21 she was the youngest person to ever pass the test. In October of that year, the two began their romantic partnership, an experiment in personal responsibility and open-heartedness.

Before her partner’s passing, Simone de Beauvoir, who Sartre mockingly referred to as “The Beaver,” never had a written project published without his or her involvement. He also described her as a “filter” for his writings and some academics have even argued that she wrote some of them just for him. Scholars and journalists frequently charge de Beauvoir with publicly disguising excruciating jealousy attacks but there is always a “however” in life. Although her inner emotional state is unknown, it is apparent that both Sartre and de Beauvoir treated their much younger female consorts in a manipulative, frequently dishonest, and possibly brutal manner. Consider de Beauvoir’s 16-year-old classmate Bianca Bienenfeld, who was 14 years her senior. De Beauvoir introduced Sartre to her boyfriend shortly after the two ladies started their relationship. He immediately set out on a quest to woo Bienenfeld. De Beauvoir instructed Sartre to cease their love entanglement when it developed and in a letter, he did so suddenly.

In the end, what do we make of these encounters, engagements, marriages, affairs and existential, trauma-bonding, soul connections? They are perhaps, emblematic but undeniably flawed, even dangerous, and not ideal to look up to, if not looking for inspiration to write a thrilling romantic novel. As de Beauvoir stated in her relationship with Sartre, “We were two of a kind and our relationship would endure as long as we did: but it could not make up entirely for the fleeting riches to be had from encounters with different people.” Love, passion, and obsession only grow as we feed into them. And again, when a relationship ends, maybe it is not about the people stopping loving each other, but rather the people stopping hurting each other.

References

-

5 Toxic Romances From History. historyanswers.co.uk. Available here

-

29 July 1565 – The marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. tudorsociety.com. Available here

-

Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre: An Existential Love Story. literaryladiesguide.com. Available here