By Fanis Michalakis,

Placoderms are a group of fish that are now extinct, living in the Silurian and the Devonian period (444-360 million years ago). The main trait that made them unique was the use of literal armor on their bodies. Usually, the plated armor was located on their head thorax and its primary use was to protect the individual from attacks, while the rest of the body was scaled or naked. What is even weirder is that the armor was so packed that even the eye was protected and it is suggested that some placoderm fish were blind! At this period, it was hard to break these defenses to get to the body of the animal below. However, some fish found a way to break through the armor with the development of teeth. The best-known example of such a case is the Dunkleosteus. If we consider the placoderms as knights in “not-so-shining armor”, the Dunkleosteus is the juggernaut you do not mess with.

The Dunkleosteus is a genus of fish with ten described species. The fossil record is incomplete as most fossils have less than 25% of the preserved skeleton. However, we can still study these fossils to learn more about the ecology of the animal, its feeding habits, and its morphology. The size of the animal is still a hot topic, with early scientists estimating that the largest species of Dunkleosteus (D. Terrellι) could reach a length of 6-10 meters and weigh 1-4 tons. At the same time, more modern studies suggest that it could not have been more than 5 meters in length and the larger individuals would weigh half a ton. Its general morphology is still a mystery because the frontal part of the body is usually preserved, while the rest is lost. A fossil that included the pectoral fin, however, led to a reconstruction of the morphology of the animal and the result looked more like a shark.

The reason for this result is that in fish, the pressure applied by the environment (feeding and survival) plays a more important role than phylogeny (traits inherited by ancestors), meaning that in similar environments two unrelated taxa of fish could develop similar traits, and strategies (convergent evolution). Although at the start it was suspected that the Dunkleosteus was a slow swimmer. This changed with the discovery of prey remains inside Dunkleosteus’s fossils. The fish found were known as fast swimmers that inhabited open waters. So, our knowledge changed once again, and today we support that Dunkleosteus could keep up with these fish and lived in deep and open waters while the juveniles lived in shallow waters.

One of the most amazing traits of these animals was their heads and their jaws. We are used to seeing fish with jaws but that was not always the case. Even today there are fish that do not have that trait and use different mechanisms to feed. The creation and use of powerful jaws gave the gnathostome fish the advantage, as they could go after bigger prey, meaning more food and more energy. Alongside the development of jaws comes the development of teeth. You cannot chew with just your gums. The Dunkleosteus was one of the first vertebrates to use these powerful jaws for feeding. The bite force was insane, reaching roughly 4,000N of force at the tip and 5,000N at the blade edge. This is one of the biggest bite forces the planet has ever seen with only large alligators and some dinosaurs having even larger and just like crocodiles, the larger the individual, the stronger the bite.

My Google search as to whether or not we would leave any remains behind after an encounter with D. Terrelli (for obvious reasons) did not give me conclusive results, since the articles could not decide whether the femur (the strongest bone in our body) breaks at 4,500N of force. Some sources say that that is its limit, while others are more generous, claiming that it can withstand 30 times our body weight, meaning 6,000N of force. Still, it is remarkable that the Dunkleosteus could shred its food before eating it, increasing its feeding efficiency. What is more interesting though, is that even though some placoderms developed true teeth, the Dunkleosteus had a different strategy. Its plates ended in sharp ends that resembled teeth, and these were used to cut its prey to pieces. These plates had a self-sharpening mechanism: as the animal opened and closed its mouth, the “teeth” clashed and got sharper from the friction produced.

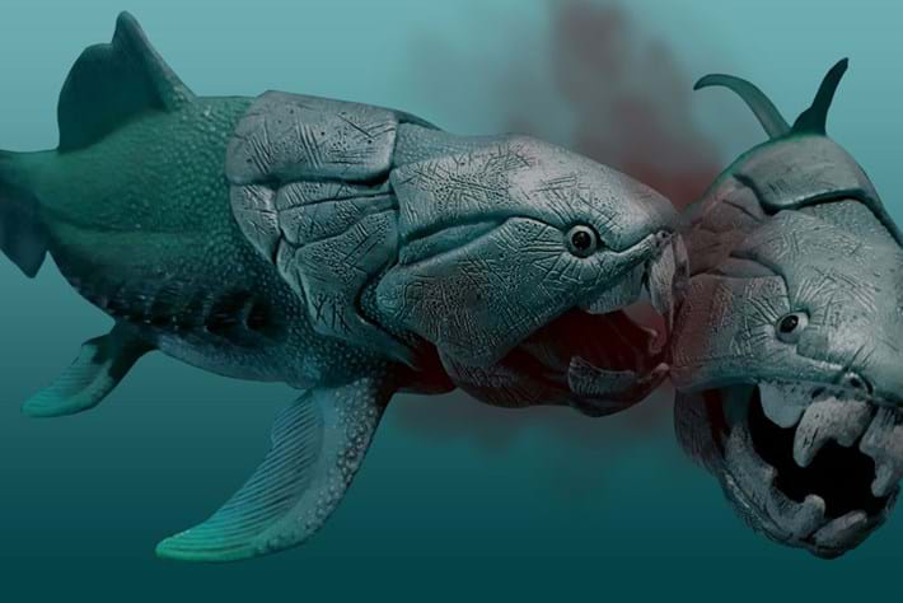

Its great bite force combined with its large body made it the apex predator of its time. Being at the top of the food chain has its bonuses. You get to eat anything you desire and you do not have to look over your shoulder for predators. Fossils found with fractures at the plates’ weak spots, combined with many marks from bites suggest otherwise. However, the only thing big enough to do that kind of damage to the apex predator of the time was one of its own. We do not know whether the fights between Dunkleosteus members were due to cannibalism and predation or because they fought for resources, but one thing is certain. After surviving the juvenile stage, the only thing that they had to fear was bumping on a bigger Dunkleosteus.

The end of the Dunkleosteus together with the placoderms came at the end of the Devonian period, with the “Hangenberg Event”, where the oxygen levels plunged. As a result, large fish could not survive, while smaller fish like sharks were able to keep up with the lower levels of oxygen, since they demanded less to stay. And so, one of the most fearsome and meanest fish came to be and dominated the seas, but even these titans were not able to adapt to the mass extinction 359 million years ago.

References

-

Crocodiles Have Strongest Bite Ever Measured, Hands-on Tests Show. nationalgeographic.com. Available here

- Brute Force: Humans Can Sure Take a Punch. livescience.com. Available here

- Ultimate Strength of the Human Femur. openoregon.pressbooks.pub. Available here

- The nasty eating habits of prehistory’s meanest fish. earthtouchnews.com. Available here

- Dunkleosteus. thoughtco.com. Available here