By Evi Tsakali,

Iceland, the Land of Ice and Fire, had always fascinated me in many ways. This country not only has a breathtaking natural beauty but is also characterized by an intriguing culture and language; and – allow me to add – incredible crime fiction. To be honest, it was through Yrsa Sigurðardóttir’s novels that I further cultivated my interest to discover more about Iceland and its people; especially their naming system, a topic on which the social scientist’s curiosity kicked in.

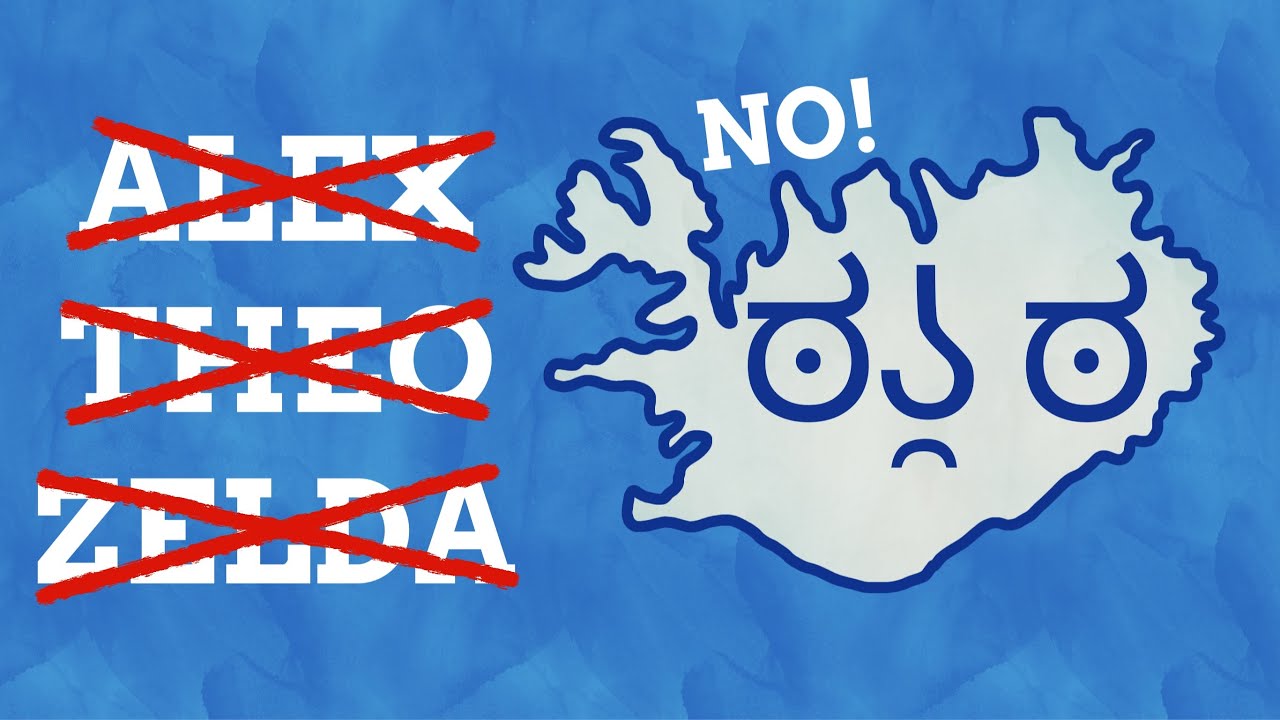

Before elaborating on why Iceland’s patronymic names are not so inclusive for some societal groups in the 21st century, let us observe how the Icelandic naming system functions.

The Icelandic naming system: Patronymics instead of surnames

Icelanders do not use surnames: instead, they use patronymics, which are formed by their father’s first name, followed by the suffix “-son” (=son) or “-dóttir” (=daughter). Consequently, many Icelanders end up having the same first name and patronymic which leads them to mainly go by their first names, which are also heavily regulated. There are gender-specific lists of first names approved by the state, from which parents can pick a name for their child during a period of six months after the birth of the child. They have the possibility of proposing a name not included in the list, however, the procedure is very restricted, since the proposed names “aptitude to be incorporated in the Icelandic language” needs to be verified, and the likelihood of it being accepted by the Icelandic Naming Committee is not very high. Until the naming, the child goes by stúlka (=girl) or strákur (=boy). All the names are listed in the Book of Icelanders (Islendingabók), an extensive database, which even Icelanders sometimes consider to be almost a national obsession.

A world where gender is binary: What about queer identities?

The suffixes meaning “son” and “daughter” immediately allude to a duality of gender, leaving non–binary individuals excluded from something as fundamental to their identity as the name that they go by and that they are registered within the public records.

This is why, in June 2019, Iceland ruled that it would now include the suffix “-bur”, meaning “child” for non-binary residents of the country, in what became known as the Gender Autonomy Act. It was only normal, and quite late, for a country that otherwise had already pioneered – in 1993 – by recognizing LGBTQIAP+ civil unions and in 2009 by electing its first openly gay Prime Minister; even the Church of Iceland has announced its willingness to welcome same-sex marriages within it.

A naming system only for Icelanders (and only those in Iceland)

The Icelandic naming system is – due to its uniqueness – incompatible with other countries’ naming systems, isolating Icelanders and setting obstacles to possible migration. The aforementioned can be illustrated by an example: if a man named Magnus Carlsson moves to Canada and has a daughter with a woman he met there, the child will have to take his surname (which is essentially not his surname) to be registered in the Canadian records. Supposing that her first name is Freya, she will be registered in the Canadian records as Freya Carlsson, and not Magnusdóttir, as it would have been in Iceland, which could cause complications on the occasion of the family’s potential return to Iceland.

However, this incompatibility does not only affect Icelanders abroad but also foreign ex-pats living in Iceland. The fact that until 1991 foreigners that moved to Iceland had to pick an Icelandic name in order to be granted citizenship is indicative of the situation.

No father, no name? Fatherless children in Iceland

In a patronymic system, what happens when the biological father of the child is unknown, or simply does not want to be in the picture? The question was instigated in Iceland mainly in the context of World War II when many American soldiers would get Icelandic women pregnant and then proceed to leave the country. This situation was called “Astandid” (=the condition), and the children that were born and abandoned by their fathers were registered under the patronymic Hansson (hans means “his”), which became the norm as the patronymic for all children that have not been recognized by a father for many years, or for orphans, being a symbol of stigma. Fortunately, today the system is evolving to gradually matronymic in such cases.

It results from all of the above that the Land of Ice and Fire is bringing its identity laws into the 21st century. We should not also forget the feminist aspect of the patronymic system, which consists of the fact that women in Iceland do not take their husbands’ names, because that would simply make no sense. However, there is always room for improvement…

References

-

Iceland’s Unique and Strict Naming Traditions. allthingsiceland.com. Available here

-

The peculiarities of Icelandic naming. Meer.com. Available here

-

How Iceland adapted law to include queer citizens. medium.com. Available here

-

Icelandic names. re.is. Available here

- Roehner, Bertrand. Relations Between Allied Forces and the Population of Iceland. Laboratoire de Physique Théorique et Hautes Énergies, UPMC