By Eirini Tassi,

Ekrem İmamoğlu, the centre-left leaning mayor of Istanbul and political opponent of President Erdoğan has been sentenced to two years and seven months in prison (DW 2022). A first-instance court in Istanbul convicted him for allegedly calling some political officials “idiots” for cancelling local elections back in 2019. It is no coincidence that this is occurring now; İmamoğlu represents the major opposition Republican People’s Party, is largely popular, and thus constitutes a robust political “threat” to Erdoğan (ibid.). Therefore, a sentence like this could very likely disqualify him from the upcoming Presidential elections of 2023. This overtly conveys Erdoğan’s intentions to sideline opposition and its respective ability to hold him and his party accountable for their governance, and thus poses a significant hit for democratic norms in Turkey. However, such an action is far from uncommon, and sadly, far from unsurprising.

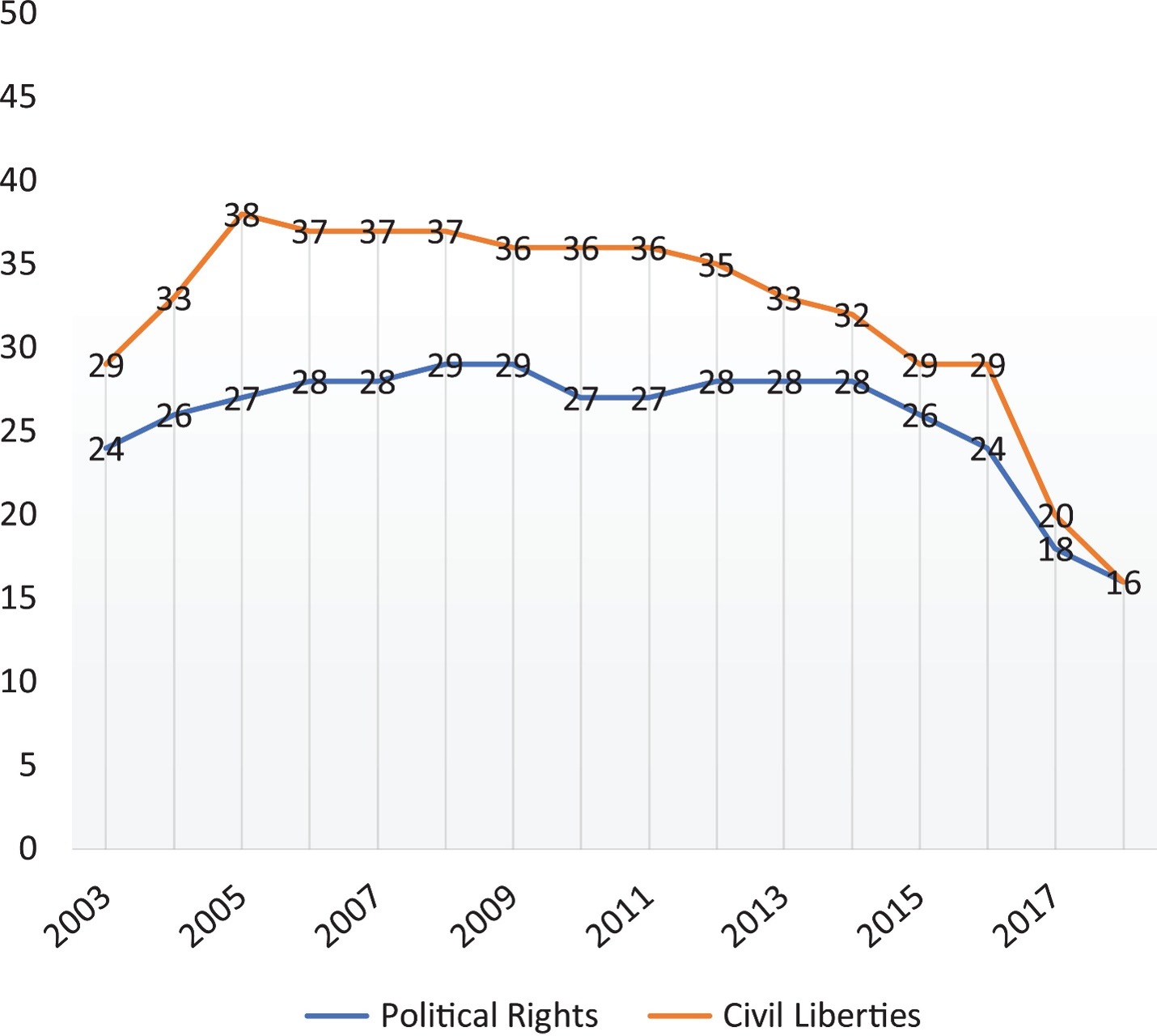

After gaining power in 2002, Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) have initiated large violations of civil and political rights throughout Turkey, especially press freedom, freedom of expression and political contestation by opposition parties. This has been particularly prevalent after 2014, where Erdoğan became President and commenced a series of constitutional hardballs to transform Turkey from a Parliamentary to a Presidential democracy. As a result, intrastate democratic foundations have significantly weakened and have distanced the country from its previously democratic status. Indeed, according to Freedom House, which measures democracy levels and other freedom indexes in nation-states, Turkey’s regime status has changed from “partly free” to “not free” in 2018 for the first time, after a little less than two decades of the AKP and Erdoğan in power (Kirişci and Toygür 2019).

Using Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s 2018 book How Democracies Die, which focuses on democratic backsliding, I will show step-by-step how Erdoğan and the AKP have subverted democracy in Turkey since their rise to power in 2002, and particularly since Erdoğan’s rise to the Presidency in 2014.

Capturing neutral arbiters

Erdoğan and the AKP have firstly attempted to co-opt and repress neutral arbiters within Turkey. These entail the de jure objective actors that inspect and regulate the actions of incumbent leaders (ruling party, head of government) and other political actors, and include the judiciary, legislative bodies, tax authorities, civil servants, state security authorities (police) and other such agencies. Capturing such actors allows the regime to effectively bypass institutional checks and balances, and practically govern in a framework where following rules is -to an extent- merely suggestive. Arguably, judicial independence has experienced the largest backsliding, with the AKP principally capturing the judiciary through institutional reforms, clientelism, repression and co-optation.

Notably, Digdem Soyaltin-Colella states that the AKP initially strengthened judicial independence from the executive in new reforms during 2010, in line with liberal-democratic conditionalities for Turkey to enter the European Union (Soyaltin-Colella 2021: 448-457). However, they then extensively altered such reorganization in 2014, allowing the Ministry of Justice to determine the configuration of the chambers of the High Council of Judges and Prosecutors nearly unilaterally, and to directly impose appointments and transfers of such judicial members (ibid.). This in effect limited judicial independence from the executive and allowed the Ministry to intimidate Council members to push them to align with AKP-party interests, or even terminate anti-government ones altogether to replace them with loyalists (ibid.). Notably, after public prosecutors began a corruption investigation against Erdoğan and important members of his cabinet, several of them were released from their judicial posts or were transferred out of the First Chamber of the Council, getting replaced with pro-government actors (ibid.). These were in turn bribed with perks and government benefits to remain aligned with the AKP’s agenda. The Istanbul’s Chief of Police was also fired alongside 350 police officers for contributing to the anti-corruption effort (ibid.).

Furthermore, the party also sought to limit the Court of Auditors, consisting of several public servants who overview government spending of public budget. Soyaltin-Colella argues that they implemented new legislation in 2010, which compromised the auditing mandate of the Court by exempting numerous public institutions from auditory inspection of their government-budget spending, like the Housing Development Administration, and which also allowed such agencies to provide incomplete and overall minimal transcripts to the Court of Auditors (Soyaltin-Colella 2022: 7-10). Such reforms allowed the AKP to largely bypass checks on their financial activity and in effect laid concrete ground for government corruption to occur.

The aforementioned actions, and more, have shaped a dangerously asymmetric framework of governance, with a very powerful executive on one hand, and largely monitored and controlled institutions of accountability on the other. Capturing such arbiters allows them to rule nearly unmonitored, permitting them to in turn repress opposition actors.

Cracking down on opposition

Erdoğan and the AKP have systematically harassed, co-opted, and repressed opponents, aiming to weaken their political influence and in effect their ability to function as democratic watchdogs of their regime. Their attempt to now silence Ekrem İmamoğlu is a principal example of this, as he constitutes rigid competition against Erdoğan in the June 2023 Presidential elections, and his sentence can potentially disqualify him from running. But political representatives are not the only actors that meet this fate. Undeniably, the press has taken the biggest hit.

The regime has enforced several civil and criminal laws that legally punish those who voice criticism of the AKP and its ideological agenda on account of “defamation”. Article 125 of the Turkish Criminal Code, for example, subjects individuals to judicial fines or imprisonment if they have “harm[ed] the honor, reputation and dignity of a person” (Gürkaynak and Yıldız), and has been arbitrarily used to repress criticism of the AKP by labeling it as such harm. Notably, left-leaning journalist Ender İmrek was charged in 2020 under that legislation for “insulting” the Turkish First Lady, Emine Erdoğan: he voiced his disapproval of her holding an expensive designer handbag in public while Turkish people are sinking into economic depression (Duvarenglish 2020). He ended up getting acquitted (ibid.), but such an experience was nevertheless explicit press intimidation, and could hinder the journalist’s capacity to pose such regime criticism in the future. The handling of the case itself was also problematic, as the indictment (i.e., official judgement of accusation) prepared by the public prosecutor was vague and insufficient in its justification of İmrek’s charge, but was nevertheless accepted by the first-instance court handling his case (Dolar 2021). This would rarely occur with impartial judiciaries, but of course, after Erdoğan’s extensive co-optation and repression of such arbiters, as discussed above, Turkey’s current judicial officials are far from neutral. This does not just allow Erdoğan and the AKP to pass inherently unconstitutional legislation like the defamation bills, but it also permits their loyalist judicial “clients” to prosecute and sentence anyone, and for anything.

The result? One third of imprisoned journalists globally are held in Turkish prisons, with nearly 200.000 cases opened under such defamation laws between 2013 and 2019 (Dolar 2021). Even those who have escaped such persecution are constantly warned that this is where they will end up should they continue to criticize the regime and its ideological agenda on any grounds. Therefore, the press is becoming less and less able to hold Erdoğan and the AKP accountable whenever they implement oppressive and/or problematic policymaking, leaving Turkey’s remaining democratic norms with dangerously few watchdogs.

Legislative & constitutional reforms on their terms

Having few to no democratic watchdogs in turn allows the Turkish incumbents to produce several institutional changes which consolidate their executive power and weaken checks and balances imposed to it (Barmeo 2016). Levitsky and Ziblatt (2018: 51) argue that these reforms usually occur after an intrastate crisis and are implemented under the façade of a public good in order to be adequately legitimized. In particular, following the attempted coup d’état against the AKP government in 2016, Erdoğan declared a national state of emergency and implemented several constitutional changes in claims of protecting national security. These involved the use of executive decrees to govern and implement policymaking, which allowed him to significantly bypass the veto authorities of the Grand National Assembly, the unicameral legislature of Turkey. Furthermore, he enforced rigid constitutional reforms to transition Turkey from a parliamentary to a presidential regime, in an overall effort to centralize state power to himself. Indeed, President Erdoğan has approved 2,229 legislative bills since Turkey’s transition into a presidential regime in 2018-2020, of which only 1,429 have been reviewed by the Assembly (Soyaltin-Colella 2022).

Such reforms are particularly alarming, and with the increasing absence of journalists, political opponents, the judiciary, and the legislature as democratic watchdogs, they allow Erdoğan and the rest of the executive to alarmingly undermine democratic norms within Turkey. And unfortunately, this backsliding does not seem to be experiencing any hopeful democratic upturns. Could this ever be reversed? And if so, what could be a solid way of pushing the regime to gradually conform to liberal-democratic governance? Kirişci and Toygür argue that the answer partially lays in transatlantic relations: Turkey is economically and geopolitically tied to both North America and Europe and they could thus push for a long-run conformity to impartial and independent judiciaries, press freedom and other such democratic prerequisites through credible conditionalities towards the regime (Kirişci and Toygür 2019). But then again, Erdoğan has shown no problem in conflicting with European allies, as seen for example by his provocation of EU territorial sovereignty in the Greek Evros border in 2020, so perhaps such conditionality should be principally brought upon by the United States. Whatever the optimal solution turns out to be, it is right now crucial for the international community to systemically scrutinize and monitor the trial of mayor İmamoğlu in the Court of Appeal, and to pressurize Turkish political institutions to follow, in any possible extent, liberal-democratic prerequisites throughout the whole process.

References

-

“Erdogan rival sentenced to jail for ‘insulting’ officials”. dw.com. Available here

-

“Turkish journalist Ender İmrek acquitted in ‘insult’ case concerning Emine Erdoğan’s Hermes handbag”. duvarenglish.com. Available here

-

Bermeo, N. (2016). On Democratic Backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 27:1, 5-19.

-

Cem Berk Dolar, “Analysis: Turkey’s judiciary and press freedom: Farewell to a fair trial”. freeturkeyjournalists.ipi. Available here

-

Corke, S., Finkel, A., Kramer, D. J., Robbins, C. A., and Schenkkan, N. (2014). Democracy in crisis: Corruption, media, and power in Turkey, 1-20. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

-

Gürkaynak, G., and Yıldız, C. “Defamation and Privacy Law in Turkey”, Carter-Ruck.

-

Kirişci, K., and Toygür, İ. (2019). “Turkey’s new presidential system and a changing west. Implications for turkish foreign policy and turkey-west relations”, Brookings, 1-17.

-

Levitsky, S., and Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

-

Soyaltin-Colella, D. (2022). “How to capture the judiciary under the guise of EU-led reforms: domestic strategies of resistance and erosion of rule of law in Turkey”, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 22:3, 441-462.

-

Soyaltin-Colella, D. (2022). “When does bureaucracy function in autocratizing regimes? the court of auditors in Turkey”, Turkish Studies, 1-22.